Our project on dust is now approaching the half-way point. The project, which started in 2013, aims to identify the risks dust poses to our collections. Dust can be composed of a variety of particles, including building materials, airborne pollutants, hair, skin and textile fibres. It can irreparably damage records, speed up chemical deterioration and provide food for insects and mould. By analysing samples of dust we can identify what it is made of, where it comes from and predict where it will build up and how we might tackle it.

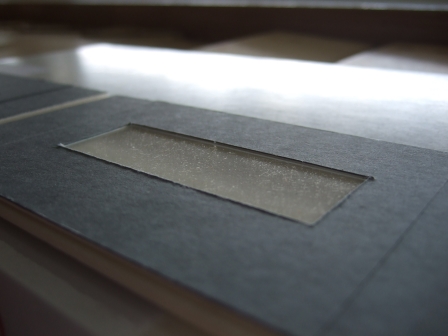

Earlier this year, we placed 88 dust monitors in locations across two repositories. The monitor uses a glass microscope slide which, when left undisturbed, collects dust on its surface. The build-up of dust leads to the glass losing its glossiness and in measuring the loss of gloss we are able to determine how much dust has accumulated.

We measure this accumulation using a Rhopoint Novo-Gloss™ glossmeter. This is an incredibly useful piece of kit. Ordinarily, it is used to measure gloss where this quality might be important, such as car body panels and magazine covers. It is a handheld instrument, which makes it suitable for us to work with in the repositories, and it works by shining light at a specific angle onto a surface to determine its level of reflectance. We take readings from a ‘dusty’ slide which we clean thoroughly before taking a second set of readings. Comparing these two readings shows us how much the gloss has been lost and ultimately, how dusty the slide is.

So far, we have measured dust fall after two and four months and we will measure again at six and 12. Early findings indicate that there are clear differences between the two repository buildings in quantity of dust falling. Areas with greater footfall seem to gather the largest quantities of dust, though some of the highest levels measured have been found on window ledges. This may be influenced by the level of air circulation in these areas, which is affected by how close they are to the air filtering system. However, overall dust fall is low compared to that in museums and historic buildings, both of which have much higher levels of foot traffic than our repositories.

The next round of measuring is due in March 2015 and we are very interested to find out what it will reveal. Ultimately, the information that we have gathered will feed into a wider strategy for understanding and managing dust at The National Archives. We have already begun a series of experiments to help us identify effective ways of removing dust from records and storage areas, and to determine whether handling causes dust to transfer from box to document (but that is a subject for another blog post…). Measuring dust build up, and examining how it behaves, will help inform our approach to preservation by identifying the impact that dust has on our collection, whether we are managing it effectively and what steps we can take to reduce risk.