Today sees the release of the concluding tranche of records relating to compensation claims of British victims of Nazi persecution. Beginning in March 2016, today’s fourth and final release of just over 1,000 records marks the completion of the collection.

These files detail each applicant’s case and can include evidence of internment, medical disability claims, reactions to the outcome of awards, and the decision making process of the Foreign Office officials who administered the scheme. Some files also contain first-hand testimony of experiences. Accordingly, these files, held in the series FO 950, not only offer a complete insight into the Anglo-German compensation agreement but also provide thousands of first hand accounts of mistreatment and unlock personal accounts that may otherwise have been lost to history.

We outlined the terms of the scheme in our previous blog and alluded to its strict eligibility criteria. Among them were three key conditions:

- the claimant must have been held in a ‘concentration camp or comparable institute’

- the claimant must be British born or naturalised British before October 1953

- even if the claimant was a dual British national, they would not receive compensation under the British scheme if they were eligible under any other compensation schemes

This somewhat narrow definition caused contention among those who had faced various – apparently ineligible – forms of mistreatment at the hands of the Nazis. Indeed, only 1015 claims were accepted. Just over 3000 were rejected; 913 on the grounds of nationality, 332 were eligible for compensation elsewhere and 1677 were ineligible on the grounds they were not held in a concentration camp or comparable institution.

Because of this, the files show a vast range of experiences – both eligible and ineligible for the scheme – and demonstrate the extent and reach of this persecution, with many applications from foreign-born individuals who made Britain their home in the aftermath of the war.

As the previous blog focused on individuals held in concentration camps and ‘comparable institutions’, here we have chosen to highlight two collective cases that fall outside what might be expected within the collection, but nonetheless provide moving stories of suffering and hardship.

Irish-born merchant seamen

Among the files sits a number of Irish-born merchant seamen (files FO 950/5174, 5176, 5178, 5182, 5183, 5186) whose ships were captured or sunk during the war. Once in German hands, these men were taken to the Marlag-Milag Nord prisoner of war camp in northern Germany. This camp complex held captured merchant and naval seamen throughout the war despite the fact that, as civilian non-combatants, the former should have had the right to avoid captivity by signing a statement not to undertake war service.

What makes these cases interesting is that they were proactively contacted by the Foreign Office because one of their number – whose application qualified for compensation – provided a list of their names. Because of their connection by birth to neutral Ireland, all were asked if they would work on the railways at Bremen or in the shipyards at Hamburg and, in effect, help the German war effort against the Allies. When they refused all were sent to the Bremen-Farge concentration camp as punishment – a sub-camp of the Neuengamme complex – and were made to do forced labour. The accounts speak of poor conditions, disease, torture and execution, and all those traced appear to have been compensated.

Libyan Jews

Another interesting, and often forgotten, story highlighted is the plight of Libyan Jews (files FO 950/4163, 4194 and 5187). The relatively small Jewish communities in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania in Italian Libya suffered increasing hardships from 1938 onwards with the introduction of anti-Jewish legislation (similar to the legislation against Jews across Nazi-occupied Europe). Their hardships only increased with the fighting that took place over the same ground during the war.

Many of those who were unable to escape under the intermittent periods of British occupation between 1940 and 1942 were sent to Italian-run detention and concentration camps in Libya, before being transported to camps in Italy and, in some cases, Germany. File FO 950/5187 outlines the Foreign Office’s understanding that up 300 North-African Jews came through this route and ended up in Bergen-Belsen, before being transferred in 1944 in three or four groups to one of two civilian internment camps. They were later released under an exchange agreement.

The unnamed individual in file FO 950/4163 claims to have been transferred to several camps in mainland Europe, including Germany and Orleans, France. He managed to escape during a transport between camps and evaded capture until the liberation of France, aided by resistance fighters from the Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur (FFI). His claim, however, was rejected as he was never held in concentration camps. Khlafo Buaron (FO 950/5187) provided a similar story but claimed to have spent time in Bergen-Belsen, but, as he and the FO were unable to prove this, his claim, too, was rejected.

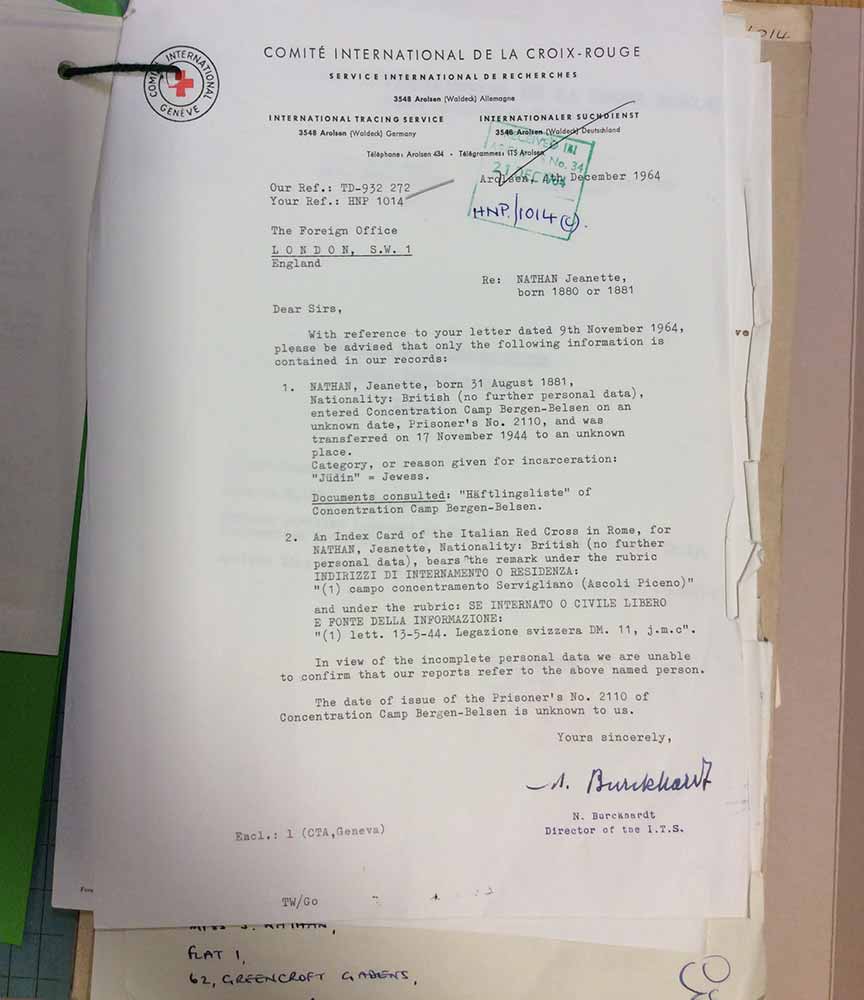

An example of evidence provided by Jeanette Nathan to support her claim that she was held in Belsen and Biberach. Certificates provided by the International Tracing Service were the preferred form of evidence. (Catalogue reference: FO 950/1842)

These cases provide the briefest insight into the rich history contained within this collection. These personal accounts are invaluable in aiding our understanding of the extent and nature of mistreatment, violence and persecution done in the name of Nazism. Though they naturally lean towards what might be considered a British experience, the nature of the scheme means there is a huge variety of witness testimony from those naturalised British after the war.

Although Britain (outside of the Channel Islands) was never subjected to Nazi policy and thus did not experience the sort of systematic persecution meted out in Germany, the Netherlands, France, Poland or Hungary (to name but a few), these files show that British citizens were also not spared from Nazi persecution. Indeed, the files provide a unique – and previously untold – insight into the persecution experiences of those British people who had made their homes elsewhere before the war, as well as those who later sought refuge in Britain after it.

Related blogs

How were British victims of Nazi persecution compensated?

What happened to refugees and Displaced Persons after the Holocaust?

The issue of the names not being in Discovery is a major issue (there are currently about 130 which should be released and are still closed because the people are dead or 100 years old and there must be many more than can/should be opened). The case files do highlight how people were moved through various camps even Auschwitz to other camps, when one would expect that they would not leave Auschwitz. There are at least three cases of ‘renegades’ (i.e. German spies) who were paid money when there was overwhelming evidence of their actions but presumably our Security Services didn’t want to alert them to the fact they had/were being monitored. It would be fair to say that members of the Special Operations Executive got money although they were not supposed to be covered by the scheme. If claimants had already received monies from other governments then they would not be paid a second time. There are of course still a number of files that the FCO are still sitting on, including the full list of claimants.