Vicky Iglikowski-Broad is currently doing a professional fellowship with the Wellcome Collection entitled ‘Co-collaboration and challenging histories – exploring the most effective co-collaborative models to enrich heritage practice in research libraries and archives’. This fellowship seeks to address the challenges and rewards of working collaboratively to enrich our understanding and interpretation of “challenging” or “sensitive” histories[ref]Essentially, by this I mean histories that have been historically marginalised in the mainstream, where we are often presented with significant absences or biases in the records.[/ref]. This piece of work uses the sample theme of sex work and the state as its focus, to show a case study in context. Here Vicky explains how her research is going so far.

Co-collaboration and challenging histories

When I first started my fellowship with the Wellcome Collection through The National Archives partnership with Research Libraries UK, I never imagined undertaking the work during a global pandemic. While the core of the project remains the same, there has been an inevitable shift.

This moment in time has put even more emphasis on the need for compassionate and ethical collaborations. Understanding that collaborators are real people, with real lives outside the project they work on. Currently everyone is impacted in some way by the current coronavirus crisis, including sex workers.

Over two blog posts I will explore some of the records The National Archives holds relating to historic sex work in our collections, and some of the barriers and opportunities they present to audiences and co-collaborators. I was fortunate to have some access to documents prior to the temporary closure of The National Archives and through photographs I had taken in the build up to this fellowship. Because of my research background I have mainly been focusing on later 19th- and 20th-century records.

The blog will use the widely accepted term ‘sex worker’ to describe a person who is employed in the sex industry, other than when discussing the barriers of historic terminology.

The state regulation of ‘vice’

The state has had a long, complex and largely negative relationship with sex workers throughout its history and The National Archives records naturally reflect this. Archives tend to echo the biases of their creators, as can be seen in these records.

This is a sensitive subject as women, men and non-binary people involved in sex work have been historically marginalised by individuals, society and the state. The state’s attempts to regulate sex and sexuality has paradoxically left us with many potential sources through police, criminal, policy and legislation records. Ultimately, it is through the policing of sex work in the past that we are left with so many rich and insightful records, which in itself presents a contradiction.

Despite this, records can be read ‘against the grain’ of their original intentions. While we can use these records to look at the historic policing of sex work, we can also at times get a surprising insight into the lives of past sex workers, that you wouldn’t expect in a government archive. The collections are rich, informative and largely under-explored[ref]While various historians have used our significant records in this area (Judith Walkowitz, Julia Laite, etc.) it is not something we are widely known for outside of academic writing.[/ref]. While there is an extraordinary amount of material (reflecting the interests and concerns of the state in the past), the government lens clearly presents complexities.

Language in the archives

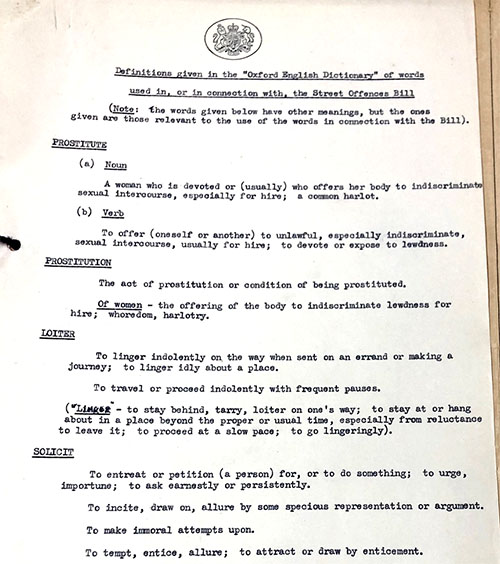

A cursory search of our collections immediately demonstrates some of the issues a government archive presents: there are no search results in our catalogue, Discovery, under the term ‘sex work’, compared to 796 results for ‘prostitute’ or ‘prostitution’. Even the terms used in our archive reflect old biases and historically outdated language.

Sex workers appear to enter our records predominantly because they themselves are criminalised in some way[ref]Selling or buying sex has never directly been illegal but many of the associated practices, such as brothel keeping, soliciting and kerb crawling, have been.[/ref] or because they are subject to a crime. A re-occurring theme is the violence women faced historically in selling sex.

A striking and controversial example in our records is the case of Jack the Ripper. These are among our most well-known records and yet the women’s voices are entirely absent[ref]Hallie Rubenhold has done great work in the archives to reclaim the stories and voices of these women, in The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper, 2019.[/ref]. This famous example is representative of many other records on this topic that we hold, that largely focus on perpetrators and men, because of the historic biases of the time.

When you search catalogue descriptions of historical records in any archive, you will generally need to use the language of the time and not expect to find items catalogued under modern day terms. This means that, even at the first point of access, the catalogue presents a barrier to engagement, such as the use of stark legal terms or historic terms with negative connotations that remove agency of the individuals.

Words commonly used include:

- Obscenity

- Indecency

- Disorderly house

- Prostitute or prostitution

- Male importuners

- Vice

This fellowships seeks to explore working with current sex workers to address some of this problematic terminology, and mitigate the impact of these words on new audiences by contextualising them and being open about the barriers these present.

In part two of this blog I will discuss the agency and personal voices of sex workers in our collections. I will also reflect on how we can start to read the records against the grain of their creators’ original intentions to reclaim the lesser-known stories and agency of past sex workers.