This blog post will use ‘LGBTQ+’ and ‘queer’ as umbrella terms to describe people historically who were either not cisgender or heterosexual. These individuals would likely have used a variety of different language to describe themselves in their own lifetimes. For more context around language and LGBTQ+ history, refer to The National Archives’ guidance on Sexuality and gender identity history.

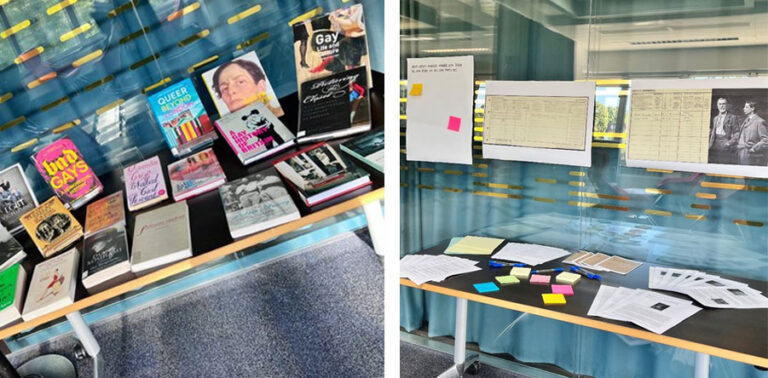

On Saturday 19 November, we held our event ‘Queer, There and Everywhere: LGBTQ+ lives and the census’ as part of the Being Human Festival, at Queer Britain, to explore what it means to have your identity remembered, represented and archived through the census.

The event was hosted by drag kings Orlando and Eugène Delacroissant, two self-described ‘heritage divas’! Through performance and creative activities, they sought to share stories of LGBTQ+ lives that have been uncovered through research in to the recently released 1921 census in a fun and interesting way.

This blog reflects on some of the questions that the project prompted us to consider, and shares a little about the final event that communicated these exciting research finds.

Census context

The census, very literally, asks us to fit our lives into boxes.

In 1921, punch cards were widely used to process census data by a pool of young girls working in an office in Acton – an innovative approach for the time. All censuses involve collecting vast amounts of demographic data, and answers had to be able to be processed in this formulaic way. But our lives and identities often don’t fit neatly into boxes. Especially for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, in a time where the government did not recognise the legitimacy of queer relationships.

LGBTQ+ people were limited by categories that did not often reflect them and their lived experiences. The nature of the census gave limited space for people to self-describe themselves:

- It offers binary gender options

- Traditional name formats

- No space for sexuality

- Guidelines were given on the expectations for listing your relationship to the head of house; this reflected traditional hierarchical, patriarchal values.

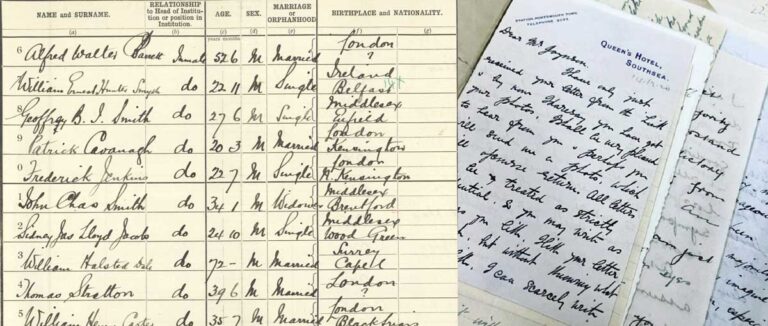

Although there is no clear evidence that people’s lives were policed based on their census entries, there would have been an instinctive fear in being too open; too honest. When looking for Ernie and Geof, lovers who met through the lonely-hearts style publication ‘The Link’ in 1920, in the census we find them not in their home in loving partnerships, but in Wormwood Scrubs, imprisoned for their same sex relationships; underlining the reality and the risk.

And yet we can still see many same-sex couples living together in the 1921 census. How open they elected to be, or felt they could be, was a very personal choice and not one without risk.

New research findings

Some initial research findings were shared at the start of the project. Since then, the research has expanded and identified key trends. Mollie Clarke has also written about queer networks in rural Kent around this time period using the census. Our state collections generally focus on criminalisation and ostracisation of queer individuals, reflecting past attitudes to LGBTQ+ lives. With this research we hope to convey that researching queer lives in the census allows a new approach, focused on the everyday domestic realities that could be possible.

Many thanks to the citizen researchers who attended the research event and helped this body of work grow. A follow on blog will explore some of this new research – look out for it soon!

The event: Queer, there and everywhere

The event was introduced by Orlando and Eugène Delacroissant, who focused on the difficulty in researching queer lives. It felt really important to be at Queer Britain, the first dedicated LGBTQ+ museum in the UK, reclaiming these past queer experiences from the census. If you haven’t visited – do!

In our expert corner, we explored examples of the 1921 census that showed all sorts of familiar family units: men co-habiting with male lovers, women living with female partners, and insights into gender-non-conforming people’s lives. From gender-transgressive pioneers like Gluck to long-term lovers, such as Glyn Philpot and Vivian Forbes.

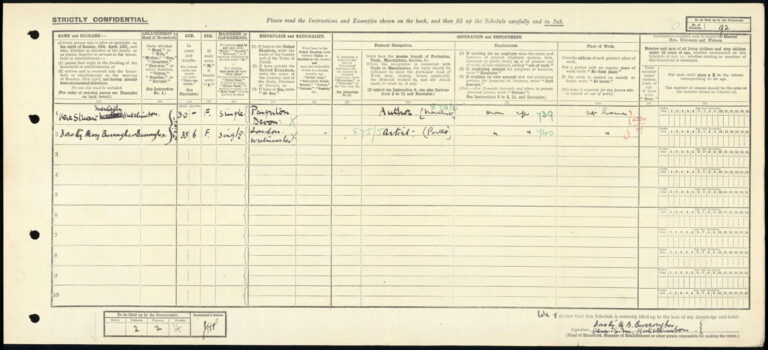

We reflected on how people choose to record their same-sex relationships and gender identities on the census, in a time that did not generally accept this variation. Some individuals, particularly women, defiantly described themselves as joint heads of household, partners or companions. This was the case for Dorothy Burroughes and Vere Hutchinson, artist and author respectively. In the 1921 census, they are listed as living together in Paddington and describe themselves as ‘joint’ head of household.

In the event, we explored census returns that showed less well-known people living together, declaring themselves to be partners or companions. A search of this sort is not enough to prove same-sex relationships, but it can prompt us to question the assumptions we might have about people, ensuring we do not always assume heterosexuality on those we are researching. There are plenty of same-sex people living together on the census – and while some probably are ‘just good friends’, many will undoubtedly be lovers.

‘Queering’ the census

Audiences enthusiastically engaged in ‘queer euphemism bingo’, to find as many as possible phrases LGBTQ+ people used in the past to describe their relationship to the Head of Household.

Then we got creative! We used zine-making to present and reframe past census forms via collage. People created their own ‘queer census’, encouraging us think about how rarely our lives fit into the neatly defined boxes from the 1921 census.

The event highlighted the unexpected parallels between LGBTQ+ life now and 100 years ago, and the challenges we still face in recording and archiving our identities. We hope our visitors left the event feeling surprisingly connected to people’s experiences in these hundred-year-old census pages.

The 2021 census was the first England and Wales census to explicitly ask about sexuality and gender identity. The counting of LGBTQ+ lives on the census has been called for by activists for decades, but is not without controversy (see footnote 1). Many of these debates about how our lives are recorded and archived continue. My life does not fit neatly into the categories in the 1921 census – does yours?

We hope to hold more of these kinds of events in the future. Watch this space!

Thanks to our funders, Being Human who made this event happen! Being Human is the UK’s national festival of the humanities, run by the School of Advanced Study, University of London, with generous support from Research England, in partnership with the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the British Academy.

Footnotes

- LGBT activism and the census: A battle half-won? By Laurence Cooley, February 11th, 2019. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/gender/2019/02/11/lgbt-activism-and-the-census-a-battle-half-won/