One of the early casualties of the First World War was, in many respects, the community pub or, more accurately the liberal consumption of alcohol on licensed premises. Before the outbreak of war, and partly because of the rising support of the temperance movement, urging the moderate consumption of alcohol, licensing laws began to restrict the opening hours of premises. But, immediately after the outbreak of war in August 1914, Parliament passed the Defence of the Realm Act which covered a range of measures to support the Allied effort of the war. A section of the Act looked specifically at the hours in which publicans could sell alcohol, as it was strongly believed that high levels of alcohol consumption would have a negative impact on the war effort. It therefore restricted opening hours for licensed premises to lunch (12:00 to 14:00) and later to supper (18:30 to 21:30).

But, even with these changes in force, the British Government became increasingly concerned about how the high levels of alcohol consumption still threatened the productivity of the war effort and high work ethics. If anything, consumption was increasing because in many cases wages were rising, particularly for those in industries vital to war, such as shipbuilding, as overtime became the norm. A campaign to persuade people to consume less alcohol led by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George, had little effect, so in October 1915 the British government announced a further series of measures they believed would reduce alcohol consumption further. A ‘No Treating Order’ laid down that any drink ordered was to be paid for by the person supplied, so to dissuade rounds of drinks or drinks on credit. The maximum penalty for defying the Government order was six months’ imprisonment.

However, the government also became increasingly concerned about the increase in alcohol consumption in specific areas of the country vital to the war effort. An enormous cordite munitions factory built to supply ammunition to British forces had been established in the town of Gretna, just over the Scottish border, 12 miles north of the English city of Carlisle, employing over 15,000 workers. Although most of the workers were well-behaved, the cases of drunkenness, anti-social behaviour, and resulting convictions quadrupled. There was also a heightened risk of hampering the war effort through increased sick absences and the threat of serious accidents as workers had to manually handle nitro-glycerine and guncotton into cordite paste, and load the matter into shell cases.

In June 1916, in a decision involving both central Government and the local authorities, the newly formed Central Control Board took control of five local breweries and 363 licensed premises covering 300 square miles including parts of north and west Cumberland, south west Scotland, and the city of Carlisle, ‘for the duration of the war and 12 months thereafter’. The Scheme became known as the Carlisle Experiment and its records are housed in two series of records at The National Archives: HO 185 and HO 190. Both series record how the Board achieved this and how they further controlled the drinking habits of individuals, without resorting to restricting personal liberty. The Board acted quickly, closing nearly 40% of public houses by 1917 and revoking all off-sales licenses. All advertising referring to alcohol was illegal and a ban was placed on the display of liquor bottles in windows. Within the state-owned public houses (many of which remained state-owned until 1971), strict opening hours were enforced, the managers became government employees on a fixed salary and offered no inducement to increase alcohol sales (in fact, commissions were given to the sales of non-alcoholic drinks and food only). The sale of food was actively encouraged and ‘snug’ bars were re-purposed as eating areas. Pubs were made to be attractive to women and families and table service was introduced. Drinks prices were fixed by the state, to avoid competition between the different pubs. The sale of ‘chasers’ – spirits accompanying beer – was banned. The only beer to be served was that brewed by the local, government-owned brewery. This was brewed at a reduced level of alcohol or was, effectively, watered down. Furthermore, it was also prohibited to serve alcohol to people under the age of 18, as was the selling of spirits on Saturdays.

By the end of the war, the government’s national measures were proving successful. In addition to measures introduced under the Defence of the Realm Act, the government also significantly increased the level of tax on alcohol. In 1918 a bottle of whisky cost £1, five times what it had cost before the outbreak of war. This helped to more than halve the consumption of whisky during this period. Similarly, on a national level, convictions for drunkenness also fell dramatically during the war. In London in 1914, 67,103 people were found guilty of being drunk. In 1917 this had fallen to 16,567.

But what about at the local level, in particularly in Cumberland where more severe measures were introduced? Were these more or less successful? Both series include papers relating to individual pubs and are essentially case studies. One such pub was the George Inn, in Warwick Bridge, four miles east of Carlisle. The case study of this, if typical of others, would suggest that there was mixed success. Whatever the outcome, these records form a fascinating picture of what life was like in rural England during and after the First World War.

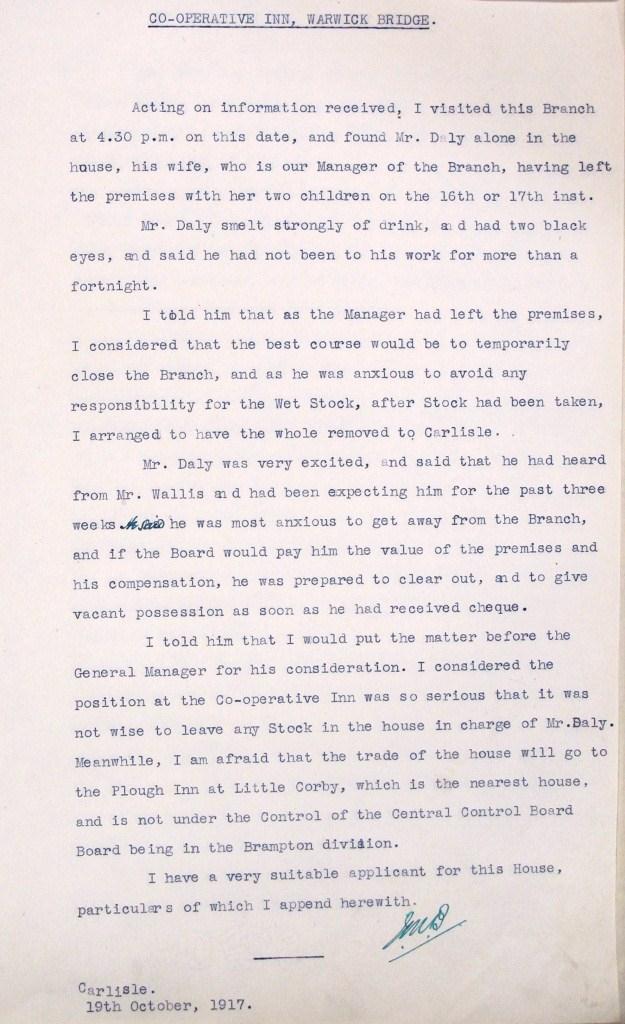

Originally called the Co-operative Inn, the pub at Warwick Bridge was renamed the George Inn in 1918 to endeavour to improve its bad reputation for drunkenness. The pub was acquired by the CCB (Liquor Traffic) under powers conferred upon the Board by the Defence of the Realm Act (No 3), 1915. The Licensee (a Mrs Daly) was informed of this on 16 March 1917; initially, the Board was content to allow the resident licensee to continue the business providing she was willing to abide by the new terms and demonstrate that she could run the business effectively. This information proved hard to get as the document HO 190/1079 shows.

Eventually, contact was made on 18 October, 1917. This resulted in an inspector’s visit, the removal of all stock, the temporary closure of the pub, the appointment of a new manager, a Mrs Mary Ann Heslop, and a new name: The George Inn!

The George Inn opened in the spring of 1918 in the hope that the new licensee would bring some order to proceedings with the support of the Board and the local constabulary. According to one ‘onlooker’ who writes to the Board on 29 November 1919, this was far from the case (HO 190/231), though this was not fully corroborated by an inspector’s visit on 5 December 1919.

The record goes on to show that following a number of approved alterations to the premises, Mrs Heslop remained licensee until her resignation in October 1928, when she was replaced by a Mr Edward James Little.

Not all of the alterations were viewed as improvements as a notice board petition shows in 1933, and which was favourably received by the Board.

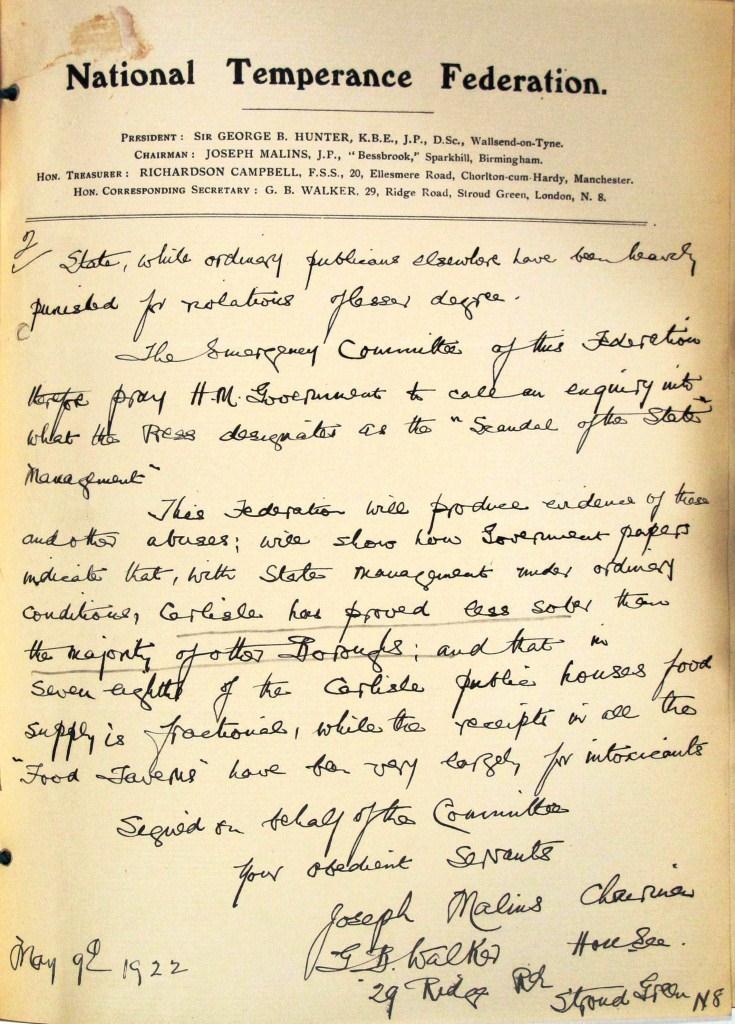

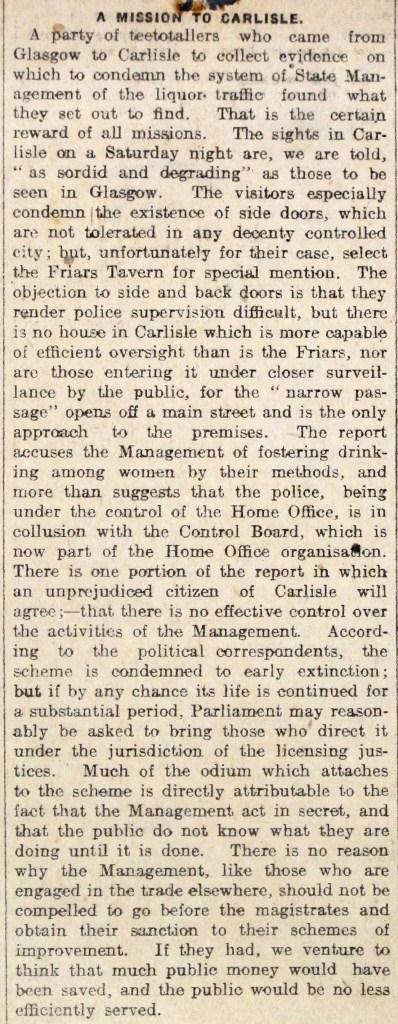

Following Mr Little’s unexpected death in 1934, his widow, Jane, became licensee. The file ends in 1937 but the Board continued to manage the pub alongside many other Cumberland pubs until the late 1960s. There was national debate in the 1920s to consider whether the British government should extend nationalisation to all pubs in England and Wales, debated at a time when the sale of alcohol in the US was prohibited. The records HO 185/17 and HO 185/22 examine this in great detail. What became known as the Carlisle Experiment had supporters as well as critics. The Temperance Movement argued that the pubs should be returned to private hands claiming the scheme had proved to be a disaster, actively encouraging women and children into premises serving alcohol.

But many felt the scheme had breathed new life into pubs, with much needed modernising and investment. Indeed, they were operating at a profit which went back to the taxpayer. In the end, the government decided against full nationalisation but to continue the operation of the Board in the Carlisle area, whilst nationally retaining many of the restrictions imposed by the Defence of the Realm Act. For example, the restrictions of opening hours remained largely in force until the 1970s, with further relaxation in the late 1980s and later in the 2000s.

Originally from Brampton, four miles east of Warwick Bridge, I began to use the George in the early 1980s. Not renowned for its real ale, it definitely had a strong community feel about it and had its own darts team, domino team and, popular in Cumbria, annual leek show entrants. It struggled with the smoking ban and downturn in the economy and had its fair share of anti-social behaviour in the new millennium, before it finally closed its doors in 2007; in its place now stands residential flats, across the road from the Co-operative food store, a link to the pub’s original name 100 years before.

[…] The UK National Archives blog published a great piece by Roger Kershaw on pubs under state management during World War I, generously illustrated with photographs, letters and […]

The NO TREATING ORDER issued in 1915 in the attempt by the British Government to deter heavy drinking in pubs.

Does anyone know if there were Government Posters printed during WW1 outlining the NO TREATING ORDER? And if so where I might see a copy?

Many thanks.

Tony Benge.

[…] The reduction in pub opening hours had come in under the Defence of the Realm Act, pubs were only allowed to open from noon–2pm and 6:30pm–9:30pm. You can find out more about the reduction in openings hours and the Carlisle experiment of government owned pubs in this National Archives blog post. […]

Thank you for this very interesting article. I have a sealed bottle of state controlled whiskey (optic) and would love to know it’s value. Do you have any idea how I could find out this? The whiskey was blended and bottled by state management districts (Scotland) Annan and Invergordon.

Thank you for any advice you can offer.

Kind regards

Bryan

Hi Bryan

I’m glad you liked reading the article. My advice to you would be to find a valuer or auctioneer close to you in the first instance and take it from there

Best wishes

Roger

Hi, this is fascinating, did you find out anymore about this whiskey? Would love to see a picture.

This is a nice piece of writing. I am just wondering if the current policy about opening time has any connection with that experiment.

Thank you so much.

Jaime

This, and other aspects of the ‘drink problem’ are considered in my book ‘Pubs and Patriots; The Drink Crisis in Britain during World War One’. Carlisle was the most extreme version of the CCB policy introduced during the war.

I am an amateur music historian; for the last there years I’ve been researching the history of pub music, from Greco-Roman times to the present day. My researches are now focused on WW1 and the impact of it on pub music. I recently came across your comment on the national archives website, and am interested in your book ‘Pubs and Patriots; The Drink Crisis in Britain during World War One’. Is it still available? Also, do you know of any other potential sources of research material that may be of interest to me?

Thank you for taking the time to read this e-mail.

Regards

Tom Hopkins

Weymouth

Dorset

P.S are you aware of the Drinking Studies Network, based at Leicester University? If not, and you’d like some info. please let me know

Thanks for your comment, Rob

For more information about the State Management Scheme, there is a useful online exhibtion here – http://www.discovercarlisle.co.uk/food-and-drink/the-state-management-story.aspx

[…] marks the 100-year anniversary of the Carlisle Experiment. Concerned about wartime productivity, in particular at munitions factories such as in Gretna, the […]

Q: what was strength of the A.B.V. of state beer?

Hi Peter. I gather it was quite weak compared to other beers so probably no more than 4%. I gather a brewery has started to brew the recipe in Cumbria and it is available in some of the former State owned pubs but I’m not sure which one

[…] After quarantine, a navvy was then able to enter the village and reside in one of the wooden huts built for the workers, and his family could then join him. Elan did have an unusual municipal canteen which served alcohol – strictly for men, with consumption limited. It was recognised that some sort of Temperance Utopia was hardly possible, although “it may be asserted that the evil results of drinking have been reduced to a minimum.” Music, singing, juggling, reciting, gambling, cards, dice, dominoes, draughts, marbles, shovel-penny, all games of skill or chance, and women were banned in the canteen. Yourdi took advice from a range of large civil engineering projects on the management of his men, including the Liverpool Corporation works at Lake Vyrnwy – it would be an interesting research project to study the exchange of management and monitoring techniques between such parties, I think it would probably be highly illuminating in terms of the ‘strategies’ of the time. Certainly the Elan experiment in “Utopian government” was widely-reported and of significant interest across the country. The canteen model was particularly interesting, with various newspapers around the country reporting on its financial model (e.g. South Wales Echo – Thursday 22 September 1898) and its management (the manager “quite understands that he is thought no more highly of if his sale are high than if they are low”: South Wales Daily Post – Tuesday 17 September 1895). I wonder if the experiment influenced Lloyd George’s own attempt at nationalised pubs in Carlisle in 1916? […]

[…] French-owned by then), and some pubs in Carlisle. Yes, that’s right, the British Government had nationalised pubs around Carlisle during WW1, to ensure that munitions workers weren’t too drunk, and with the Kaiser safely in the past, […]

[…] marks the 100-year anniversary of the Carlisle Experiment. Concerned about wartime productivity, in particular at munitions factories such as in Gretna, the […]

having just spent Christmas in carlisle and found out about the state control of pubs in these area after visiting the sportsman pub where a plaque above the bar states that the sportsman was one such pub the barmaid explained the scheme to me and gave me a leaflet about the scheme I found this very helpful and on my return home I have read all about the scheme.having been a licensee for 20years found the whole history very interesting thank you Dave Allen.

Thanks for your comments, David.

We have records of the Sportsman Inn, Head Lane, Carlisle, in the document HO 190/1250 – http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C10886916. It was as you say, under State Management. The file is likely to include correspondence with the pub and the Carlisle Office of the Board relating to all matters including inspections by the Board.