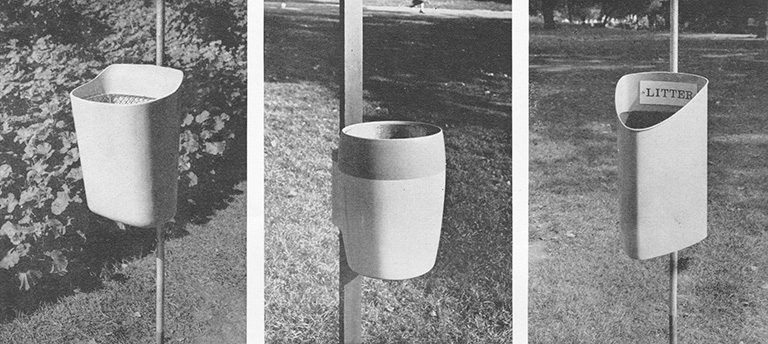

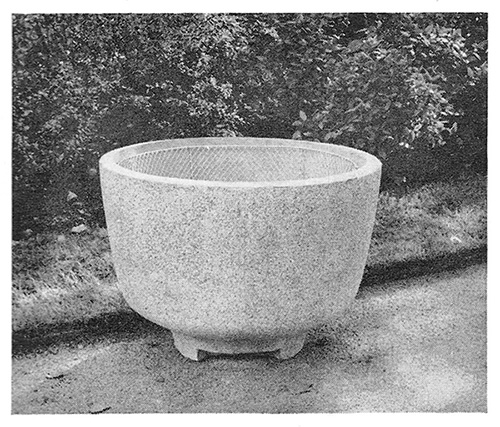

Winning bin designs from the 1960 ‘Litter Bin Exhibition’ held in Embankment gardens.

Why do our public bins, benches and bus shelters – things collectively known as ‘street furniture’ – differ in design across the UK?

A recent endeavour by a former digital public service designer to catalogue council wheelie bins across Britain has prompted enquiries about the range of colours and logo designs. Why are they not all black, or green?

The front cover of ‘Design’, the Council of Industrial Design’s magazine, from December 1960, featuring an article on litter bin design.

The question of having ‘standard bins, and a standard colour, perhaps one for town, one for country’ (as one civil servant phrased it in 1959) isn’t a new one. While in theory, a uniform design and colour seems like a relatively obvious solution considering that all citizens need their domestic waste collected, bins are looked after by local authorities, each of whom have their own idiosyncratic circumstances to accommodate. Some councils offer additional recycling or food waste disposal services and need to adopt a colour scheme to help citizens differentiate between bins, whereas others might only need to focus on choosing a design that’s unobtrusive or complementary to the local surroundings. In the case of one local authority representative likely to have looked after a built-up area, yellow bins were a real cause for concern: ‘they should be banned’, he protested, claiming that they could be easily confused with road signs. Colours have connotations to be considered too: in Liverpool, where the two colours of the city’s football teams are red and blue, the bins are purple – a mix of both.

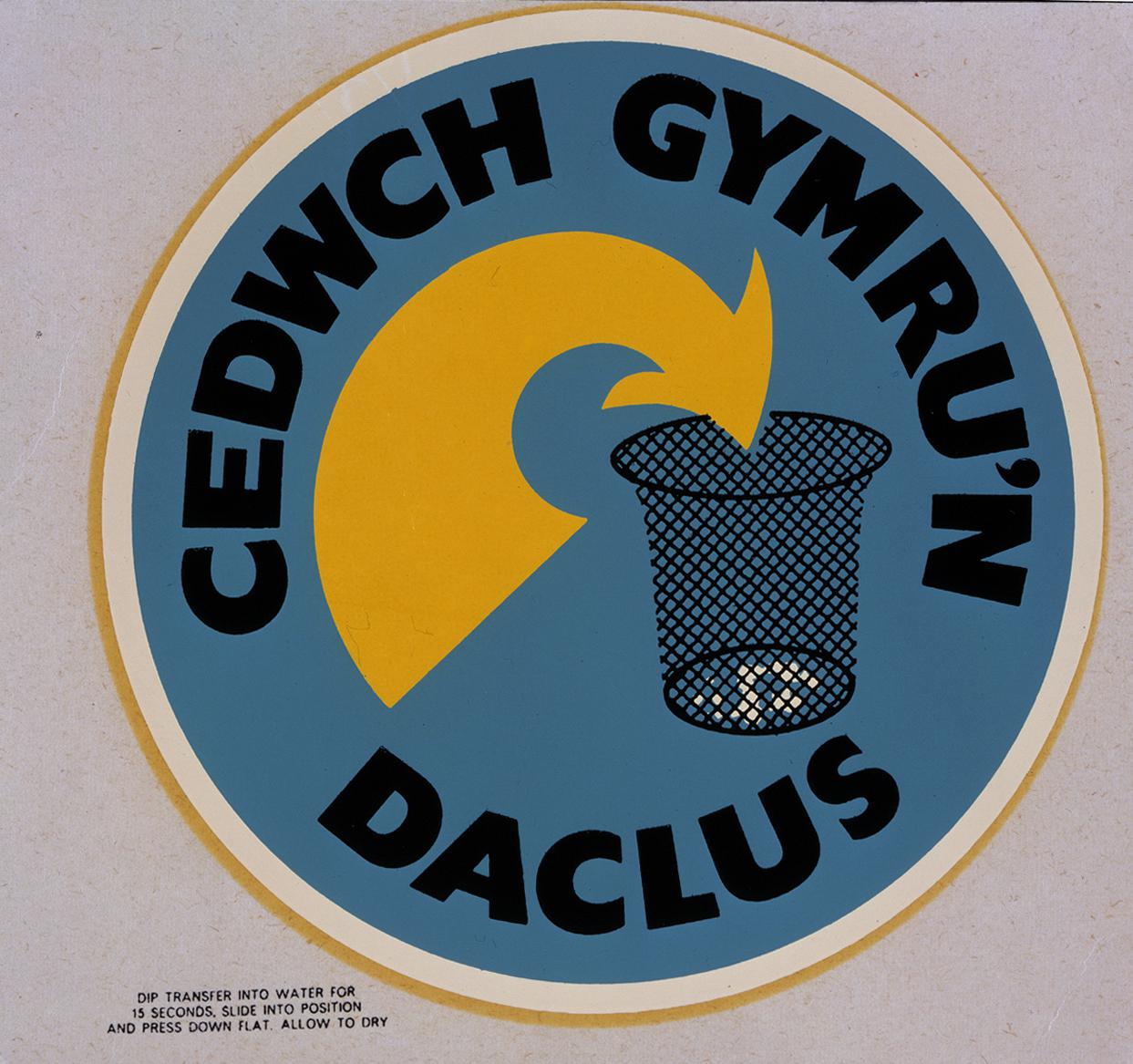

The problems of choosing a certain colour or design becomes more complex with street litter bins, for which designers need to accommodate different functions, locations, and coordination with other street furniture items. The Council of Industrial Design (now the Design Council) offered an Approved List of Street Furniture, as well as exhibitions and catalogues, to champion good design thinking and provide guidance, however local authorities ultimately made the final decisions – leading to an ever-shifting and diverse catalogue of regional street furniture designs in the process.

When litter levels significantly rose in the 1950s as a result of increased use of plastic packaging, councils had to start thinking differently about how visible their bins were. Scarborough attempted to make their bins more noticeable by changing the colour from green to cream, whereas Windsor council tried red and yellow. Whickham Urban District Council followed by painting 130 of its litter bins in pastel shades, but was then told by Durham County Council that they wouldn’t be granted planning permission to fit the bins to lamp posts until the bins had been repainted in grey.

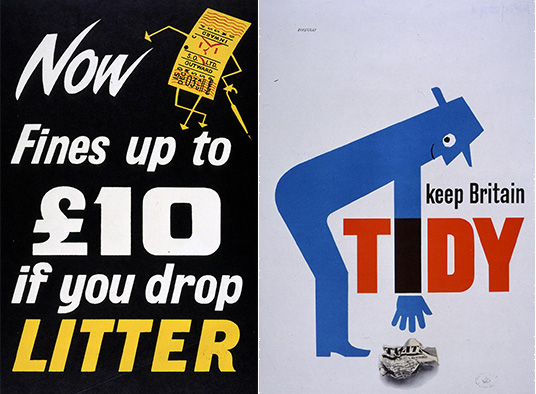

Posters from the ‘Keep Britain Tidy’ campaign, c1960s (catalogue reference: INF13-223)

Eleanor Herring explains in ‘Street Furniture Design’ how ‘these examples not only illustrate the way that local authorities resisted outside interference, but also the complexities of local government. Even within a relatively small area, it was possible to have different authorities making different decisions about design.’

To counter the litter epidemic, the Women’s Institute initiated the government-backed ‘Keep Britain Tidy’ campaign, which the Council of Industrial Design responded to by organising a design competition for inexpensive, well-designed bins for public spaces. The competition promised that successful submissions would be exhibited in a ‘Litter Bin exhibition’ at Embankment Gardens in London in the October of 1960 as well as in the Design Index and Approved List of Street Furniture.

A report assessing the success of the exhibition said that of all the visitors, it was the local authorities that gave the bins the ‘most gruelling examinations… Insides were taken out… bins were turned upside down and even thumped and tested for strength.’ A standard test by Borough Surveyors was to actually sit on a bin so as to test its appropriateness for what was apparently ‘a common use of litter bins by the general public.’

Praise was given to a design for an open concrete bin that was subsequently ‘teddy boy proof’ in comparison to other designs, and served a public that was apparently fond of throwing their litter in from a distance: ‘any bin needing careful aim was not likely to be successful’, one attendee explained. It didn’t impress a London County Council keeper however, who left miffed that nobody had considered how the squirrels could get in and scatter the contents.

The concrete bin on display at the Litter Bin exhibition that was praised for being ‘teddy boy proof’.

It was quite common to see little knots of people round a bin discussing its merits, according to the report, which gave invigilators a chance to listen in on and record opinions. ‘It was a sad comment on our standards of public behaviour that so many authorities stressed the damage done to bins, or their complete disappearance’ one wrote, after hearing a conversation between a visitor who said bins containing elements that could be taken as a trophy or a weapon would need a lock, and another who thought locks would create too much extra work for waste removal workers. The bin dilemmas weren’t limited to the exhibition space either; judging the designs at the Council of Industrial Design offices caused its own problems: ‘There was considerable discussion of the difficulties that had become apparent over the delivery and storage of bins, particularly the heavy lay-by bins… the large ones might not go in the lifts.’

Overall the exhibition was considered to be a great success. Visitors left comments saying they had enjoyed the opportunity to think about the complex mix of factors that a designer must consider when producing public amenities, and judges said that the standard of entries were so high that even the bins that didn’t make the final cut were better than many in use on the streets (one member of the public thought so highly of a particular bin that they asked if they could purchase it for use as an umbrella stand). The event also prompted a permanent exhibition of street furniture, which opened on the South Bank later that year.

It’s fascinating to see how an object as seemingly mundane as a bin – and the discussions that inform its design – can hold something more valuable: insight into public needs and how they differ. These are the things we preserve when we catalogue the objects we use to throw things away.

I was a street cleaner in Cambridge from 1975 to 2012, and bins were a constant issue – design, locations, durability, materials.

Memories:

1. Cambridge built its first indoor shopping mall, The Lion Yard, in the early 1970s. Litter bins looked inappropriate, and eventually a large circular concrete bin was installed in the centre of the Mall which would take a whole day’s rubbish. Inside this was a wire cage to lift the rubbish out with, but as it was so large we emptied the rubbish with our hands into smaller bins or

bags that we could then walk to the litter waggon on the street. This worked fine until taking drugs on the streets became popular and tolerated. So needles were thrown away in the concrete bin. And when my colleagues

came to pull the rubbish out they started getting needle stick injuries, with all sorts of associated risks. At which point a new bin had to be found.

Cultures change so quickly – no-one in 1975 anticipated needles being a common problem on city streets, or in litter bins.

2. In the early 2000s the Libdems won political power on Cambridge City Council with a manifesto that committed them to Cleaning up Cambridge’. Litter bins became the focus of local politics, and we had a whole day examining examples from diferent manufacturers. In the end the need for a quick fix led to the introduction of plastic bins – brightly coloured blue, in part to reflect ‘Cambridge Blue’, and in part to very visibly show to people that Councillors were living up to their promises.

The bins didn’t last – they were plastic, so showed up every cigarette that was stubbed out on them, and melted into wonderful shaped when the litter inside was set alight. But they served their purpose of flagging up the Libdems concern for the appearance of the streets people walked down, and later a more conventional and durable black bin made to a locally designed style was introduced – which of course came with a higher cost that had to be budgeted for. Bins as politics.