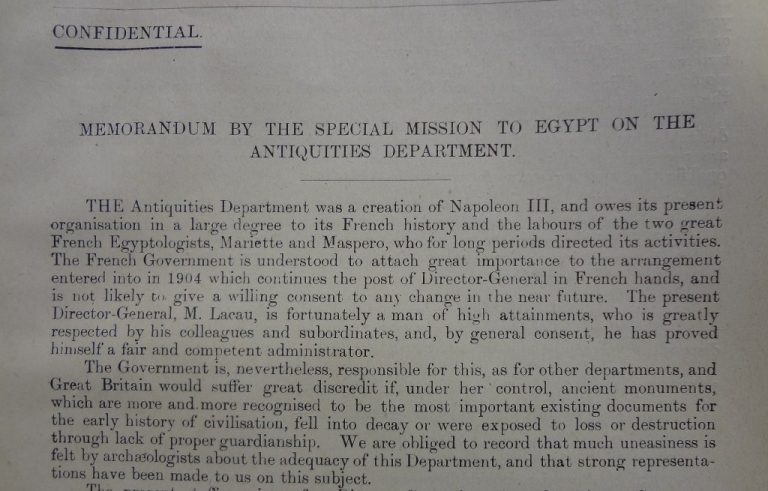

In May 1919, the British government decided to send a Special Mission headed by Lord Milner, Secretary of State for the Colonies, to investigate the causes of the 1919 Egyptian revolution, and determine the future status of Egypt and what policies Great Britain ought to implement there. The political conclusions of the Mission were straightforward enough. According to the report, the time when Britain could exercise direct control over Egypt had passed, and the aspirations of Egyptian nationalism should be acknowledged – this eventually led to independence in 1922. Less known, however, are the archaeological consequences of the Mission, in which I thought (hoped) you might be interested … A separate report on the Antiquities Department, which was in charge of everything archaeological in the country, was written, emphasising that a bad administration of the French-controlled Department could undermine the British position in Egypt.

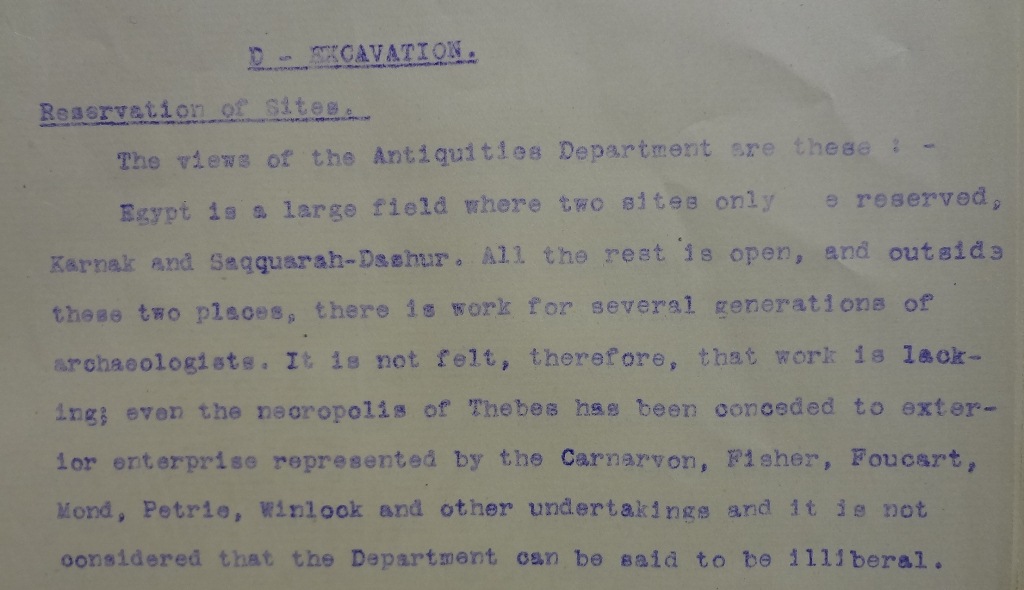

The report suggested the Cairo Museum should recruit more staff in order to ensure the protection of the artefacts. It also urged the Antiquities Department to either excavate the sites it reserved to itself or let others do so if it couldn’t secure the necessary funding, and it suggested the Department should be made independent. As a conclusion, the report stated that the Egyptian nationalist party, the Wafd, wished that the Department ‘should remain under European direction.’ Percy Marmaduke Tottenham, the Under-Secretary for Public Works, and Pierre Lacau, the Director of the Antiquities Department, composed a reply which has to be acknowledged as a masterpiece in passive-aggressive point scoring. They refuted rather curtly that the Department jeopardised historical knowledge and the monuments by reserving sites to itself.

‘Egypt is a large field where two sites only are reserved, Karnak and Saqqarah-Dashur. All the rest is open, and outside these two places, there is work for several generations of archaeologists.’ Catalogue reference FO 371/7768

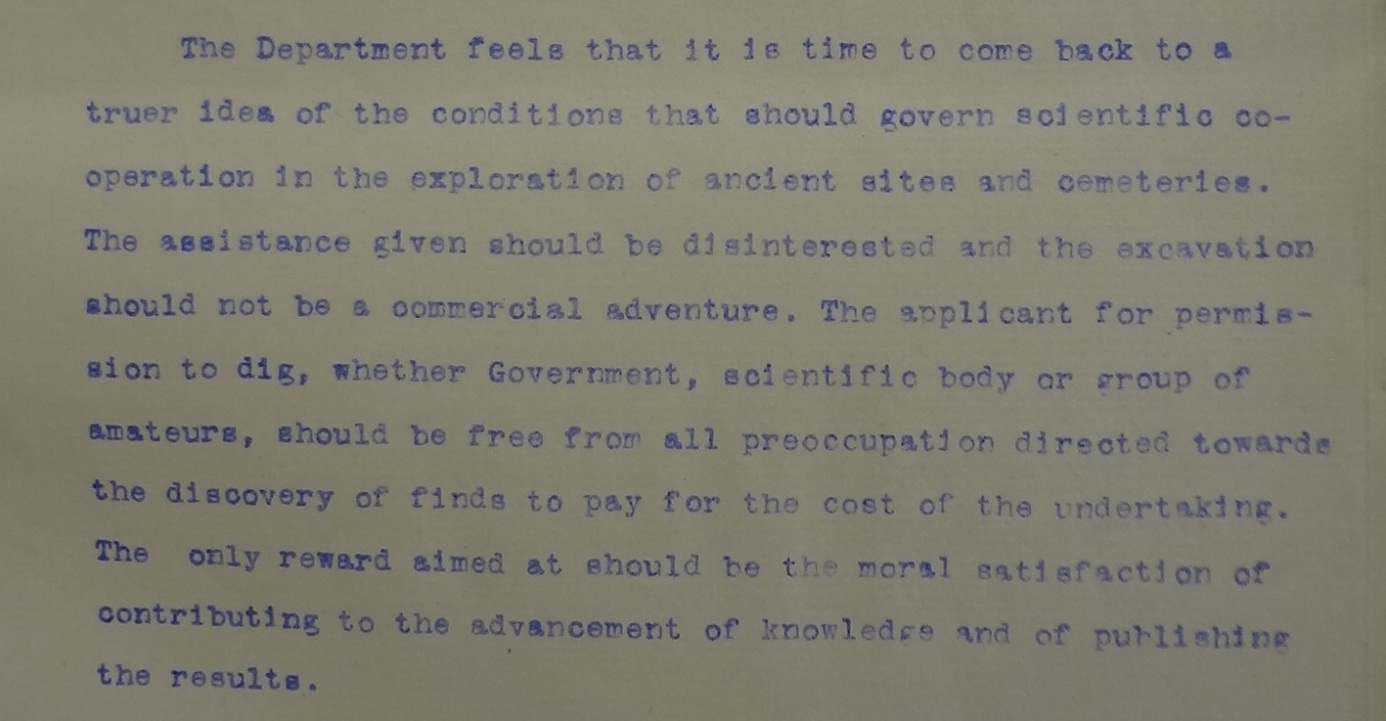

Their note stated that while the Special Mission thought the partition of finds system was satisfactory, it should rather be drastically reviewed; according to the 1912 law, the excavators received either half the find or half its value, but it was ‘common justice that historical monuments and masterpieces of Art should remain in the country as the evidence of its greatness and civilisation’.

‘The only reward aimed at should be the moral satisfaction of contributing to the advancement of knowledge and of publishing the results.’ Catalogue reference FO 371/7768

Tottenham and Lacau’s conclusion was unambiguous: ‘much criticism would disappear if the Department had something like double its present credits’ – a feeling that, I’m sure, most of us can relate to. The Special Mission’s archaeological conclusions actually had very few consequences in Egypt – even though the Department’s budget was increased. They may have found greater resonance on the banks of the Nile had the Frenchman not initiated a real revolution in the conduct of egyptological affairs – and not just for the sake of annoying the British (I think).

Tell el-Amarna, North Palace. Juliette Desplat

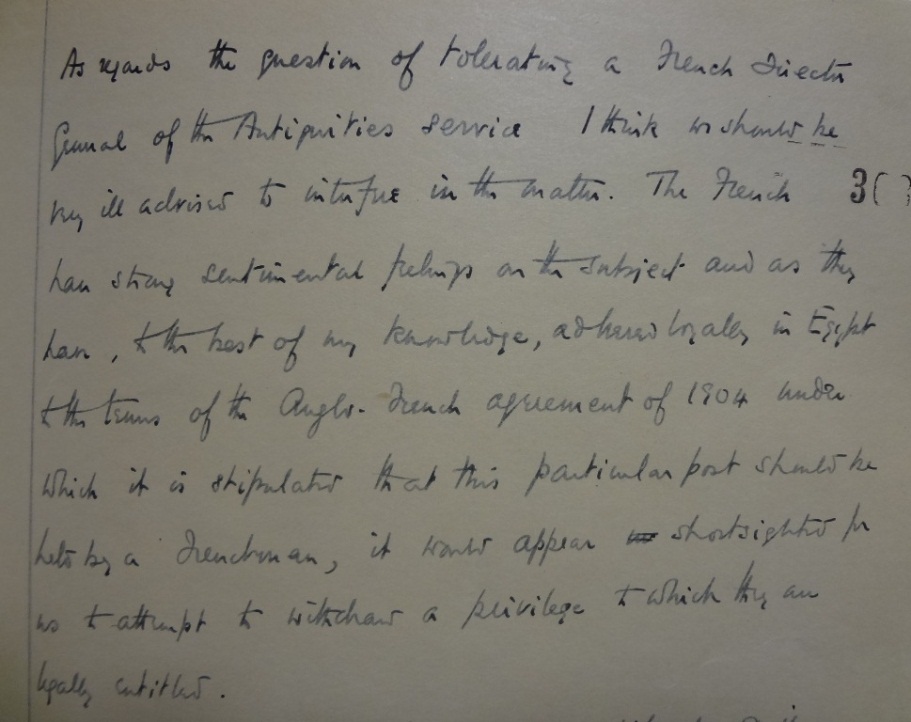

Pierre Lacau thought that any significant archaeological discovery ought to remain in Egypt as part of its historical heritage. In January 1918, he told the High Commissioner that it was ‘absolutely unacceptable that excavators should have a right on the artefacts, especially on the artefacts discovered’, and pointed out that neither Turkey nor Greece granted any material compensation to foreign excavation teams. Although this went against British archaeological practices, it triggered some interest in Egypt. The High Commissioner warned the Foreign Officethat a new law on antiquities was being prepared, which would meet with ‘very considerable opposition from all independent explorers’. In that respect, however Lacau benefited from odd and totally unexpected British diplomatic support. The High Commissioner shared his views and, the Egyptian political context becoming increasingly difficult for the British, he was in favour of a cautious approach to Egyptology, especially since, as my colleague James Cronan mentioned last month, everything archaeological had been placed within the French sphere of influence by the 1904 Entente Cordiale. When, in 1919, the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) asked for permission to excavate in Tell el-Amarna, a site Lacau wanted to reserve to the Antiquities Department, they tried to secure support from the Foreign Office. Lacau made it quite clear that he would only cede the site to ‘disinterested’ archaeologists who would excavate for the sake of science and wouldn’t ask for any kind of compensation. He also enquired whether ‘given Egypt’s new political status’ (a Protectorate had been declared in 1914) any British request had to be considered first, and informed the Quai d’Orsay of the situation. The Foreign Office’s initial reply to the EES was that, given the political difficulties that may arise, it was very bad timing indeed, but that they would nonetheless try to help. The High Commissioner, accordingly, was asked to do whatever he could to obtain the site, but his answer was rather unexpected. Lacau’s ideas, he wrote, were perfectly reasonable, and he did not wish to interfere. The EES directors stated quite openly that the British political protectorate should be transposed onto the egyptological scene – perhaps, they suggested, the time had come to consider a British Director for the Antiquities Department. The Foreign Office eventually decided to step back, probably for fear of sparking a French over-reaction. ‘As regards the question of tolerating a French Director-General of the Antiquities Service,’ they wrote, ‘I think we should be very ill-advised to interfere in the matter. The French have strong sentimental feelings on the subject, and as they have, to the best of my knowledge, adhered loyally in Egypt to the terms of the Anglo-French agreement of 1904 under which it is stipulated that this particular post should be held by a Frenchman, It would appear shortsighted for us to attempt to withdraw a privilege to which they are legally entitled.’

‘It would appear shortsighted for us to attempt to withdraw a privilege to which they are legally entitled’ Catalogue reference FO 371/3724

The political context thus weighed in favour of the French. While the Quai d’Orsay was prepared, in the long run, to give up the archaeological predominance it had fiercely defended for about forty years, the Foreign Office gave in for fear of providing the Egyptians with new reasons for discontent and unrest. It was a revolution but, against all odds, the Entente Cordiale still lived. Sort of.