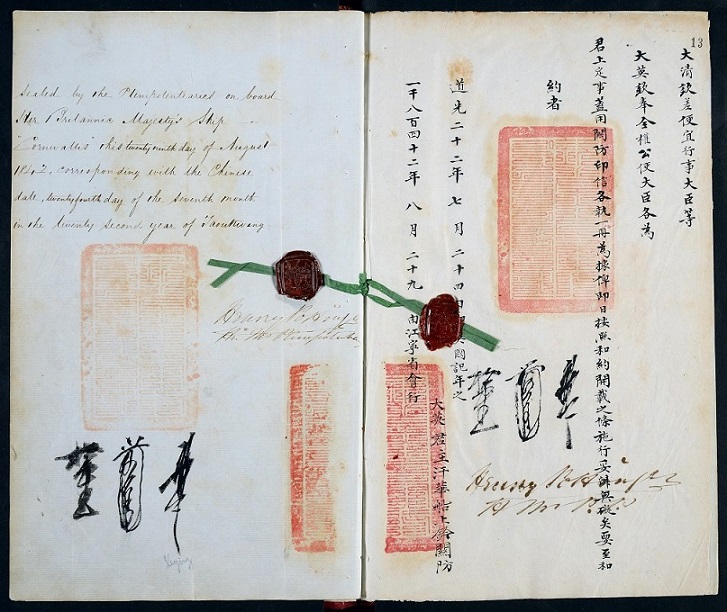

Over the past couple of months, The National Archives has been putting online our record series FO 17, Foreign Office correspondence for China between 1815 and 1905. This is one of the largest and most important series of records on British 19th century foreign policy and it is now available to researchers across the globe. Taking advantage of these new online collections, I decided to do a little digging into Anglo-Chinese relations in the early part of this period. Specifically, while the story of the ceding of Hong Kong under the Treaty of Nanking (FO 93/23/1B) and the establishment of the Crown Colony in 1843 is well known, I was less certain about the history of Kowloon, the area on the mainland directly opposite Hong Kong Island.

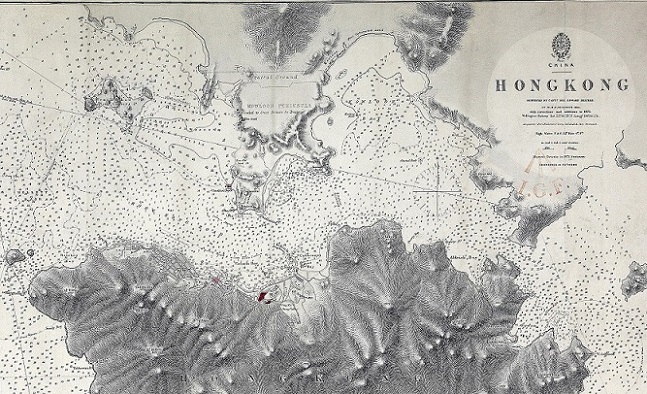

MPHH 1/421 Hong Kong Harbour showing Kowloon in 1841

Nowadays Kowloon is an extraordinary metropolis in itself, but in the mid-19th century it was a little town a few miles inland, which gave its name to the small rocky peninsular that jutted out into Hong Kong harbour. The area first came to the attention of the British government in 1841 when Lord Palmerston, the Foreign Secretary, wrote to Sir Henry Pottinger, British Plenipotentiary in China. He declared:

It seems that some portion of the opposite coast commands one of the principal anchorages of the island [Hong Kong] and it will therefore be necessary to stipulate that the Chinese shall not erect any fortification or work, or plant any cannon or station any military force within a certain distance of those points (FO 17/53, f. 96).

Pottinger did not see this as a particularly important issue and did not raise it during the negotiations for the Treaty of Nanking. In January 1843 the new Foreign Secretary, the Earl of Aberdeen, wrote to ask why he had not done as requested (FO 17/64, ff.115-6). Pottinger replied that this was not an ‘oversight’ but stemmed from him ‘thinking it totally unnecessary to raise discussion on the subject’. He went on to note that ‘the two works which the Chinese formerly built there, have long since been razed’ and that these ‘were from the first, totally untenable against even a company of Foot Solider or the smallest Brig of War’. Furthermore he noted that ‘the Chinese Government have not only evinced no disposition to interfere with the Peninsula, but appear to consider it as a part of the shore of the bay of Hong Kong’. As such it was being used by the Royal Navy for repairing ships and the Marines for exercise. Pottinger noted that a ‘considerable native Chinese village’ had already appeared on Kowloon and he was communicating with the Chinese to prevent ‘the place becoming a focus for the great and crying evil of smuggling’ (FO 17/66, ff. 249-50). Later in the year, Aberdeen replied to say that he entirely approved of Pottinger’s actions. (FO 17/65, f.22)

FO 93/23/1b Treaty of Nanking 1842 – with Pottinger’s signature

The administration of Hong Kong was at this stage a little confused, and the Colonial Office expressed further concerns about Kowloon and the prospect of it being used by the Chinese to command the anchorage at Hong Kong. Eventually they seemed content to let Pottinger’s judgement stand. (FO 17/75, f. 109)

It soon became apparent that the problems regarding Kowloon would not stem from the Chinese government. In August 1844 the new Governor General of Hong Kong, John Davis, reported: ‘[My] attention having been excited by the erection of buildings on the part of both British and American subjects on the Chinese shore opposite to Victoria (called the Cowloon peninsula) I deemed it advisable to address the enclosed letter to the Imperial Commissioner in which I declare that such proceedings are without my authority or permission’ (FO 17/88 ff. 256-7). Davis went on to issue a notification to the British merchants at Hong Kong stating that the new buildings were ‘not warranted by the Treaty and that should the Chinese Government proceed to remove them, they are not to expect the countenance or assistance of Her Majesty’s Government’ (FO 17/95, f. 300). The Earl of Aberdeen wrote to Davis say that he ‘entirely approve[d]’ of the position the Governor General had taken. The British government had no desire to be dragged into a further dispute over what they viewed as a worthless piece of land.

![CO 1069/453 Tsun [Tsuen] Wan, Kowloon 1873 - later part of the New Territories](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/01145055/CO1069-453-6-Tsun-Wan-Kowloon-1873.jpg)

CO 1069/453 Tsun [Tsuen] Wan, Kowloon 1873 – later part of the New Territories

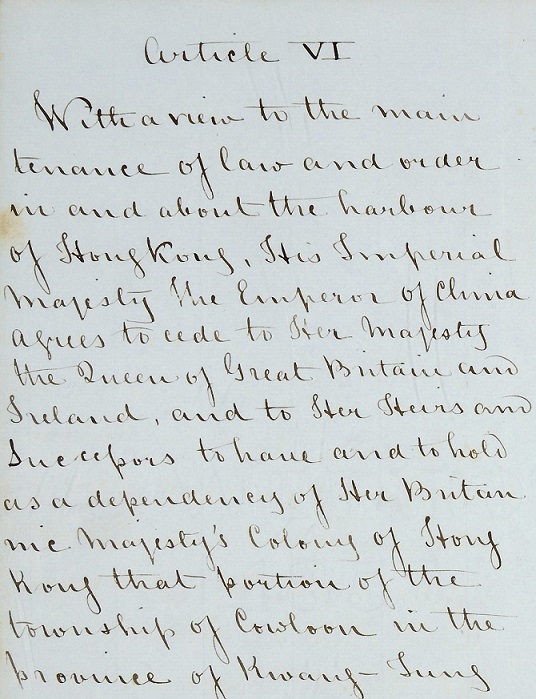

a cession of the promontory not only for the advantages which it would afford the Colony in Military, Sanitary and Commercial points of view, but chiefly for the purpose of enabling the Colonial Government to maintain order amongst the lawless population which have established themselves there and have hitherto been amenable to no practical control (FO 17/345, f. 111-113).

Following the Second Anglo-China War, Robinson got what he desired. The territory of Kowloon was ceded to Great Britain under the Treaty of Peking (FO 93/23/6). The Earl of Elgin and Kincardine, the British Special Ambassador in China, formally took possession of the territory on 19 January 1861 (FO 17/359, f. 160) The area was to form an essential part of the colony of Hong Kong until 1997 and remains at the heart of the city.

FO 93/23/6 Convention of Peking 1860 – article securing the cession of Kowloon

The FO 17 records, which are now available online, provide an extraordinary resource for anyone interested in the development of British foreign policy and the history of East Asia throughout the 19th century. The vexatious issue of Kowloon represents only a tiny fragment of the rich tapestry of stories that can be told from these fascinating records.