Nicholas Hilliard – goldsmith, portrait painter, royal servant – was buried in St Martin-in-the-Fields, at the western end of London’s Strand, on 7 January 1619, 400 years ago this year. Born in Exeter at the tailend of Henry VIII’s reign, Hilliard was about 72 at the time of his death. The nature of his final illness is unknown, though for decades he had suffered periodic attacks of both gout and melancholia.

Nonetheless, Hilliard’s was an exceptionally long and rich life, notable for the wide range of people he met and portrayed, as well as for his own journey to the heart of the Tudor and Stuart courts, where he decisively shaped the images of the monarchs he served: Elizabeth I and James I.

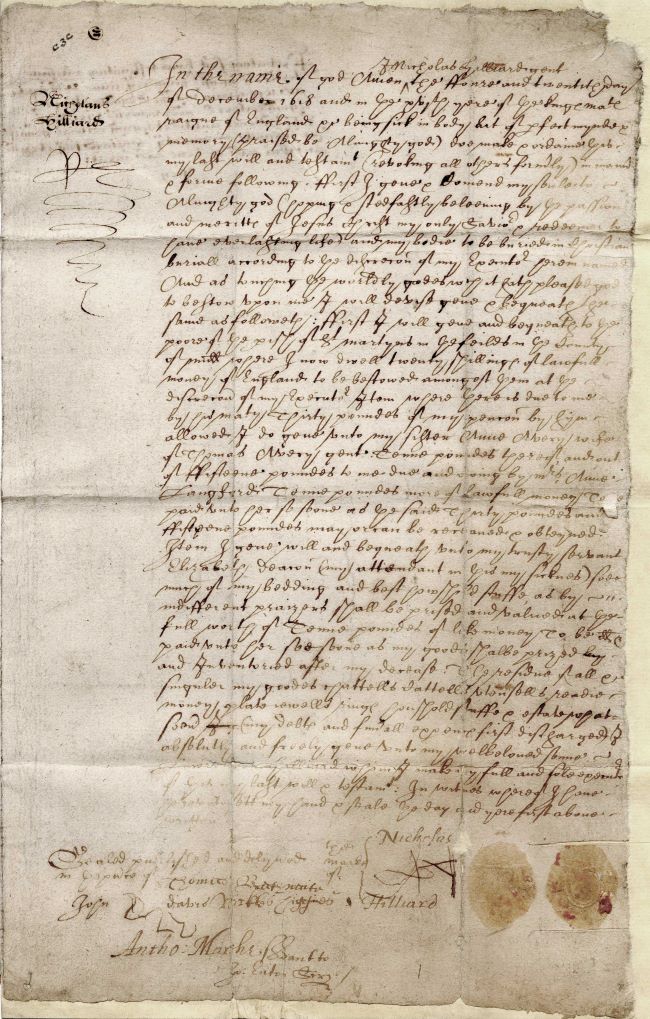

It is unclear on which day Hilliard died, but his will was drawn up on 24 December 1618 – about two weeks before his funeral and burial. The content of Hilliard’s will has long been known through the officially registered copy in The National Archives (PROB 11/133/69). A brief document, it reveals that Hilliard – who always had been hopeless with money and who, only a year or so earlier, had been imprisoned briefly for debt – possessed few material goods and little cash at the end.

The original will of Nicholas Hilliard written 24 December 1618 (catalogue reference: PROB 10/360)

To ‘the poore of the parishe of St Martins in the feildes…where I nowe dwell’, he bequeathed 20 shillings. To his sister Anne, he left £20 – though in true Hilliard fashion, he was not actually in possession of the money: £10 was to come from the last instalment of his pension from the Crown, the other £10 from a debt owed to Hilliard by one Anne Longford (which, perhaps optimistically, he expected would soon be repaid). To his servant Elizabeth Deacon, who had nursed him through his final illness, Hilliard bequeathed £10 – an amount which was to be realized by the sale ‘of my bedding and best houshould stuffe’ (though even Hilliard had doubts that these items would fetch such a high sum, owing to the ‘indifferent’ taste of others). Everything else, including some portrait miniatures executed decades earlier, Hilliard left to his ‘welbeloued sonne’ – and fellow goldsmith, portrait painter, and royal servant – Laurence, whom he appointed sole executor.

Recently, the original version of Hilliard’s will – the version, in other words, that the dying Hilliard dictated directly to a clerk – came to light at The National Archives, where it had been languishing in a box of uncatalogued, tightly-folded wills, misleadingly identified on the document’s outer cover by the name of the probate judge rather than Hilliard’s (PROB 10/360).

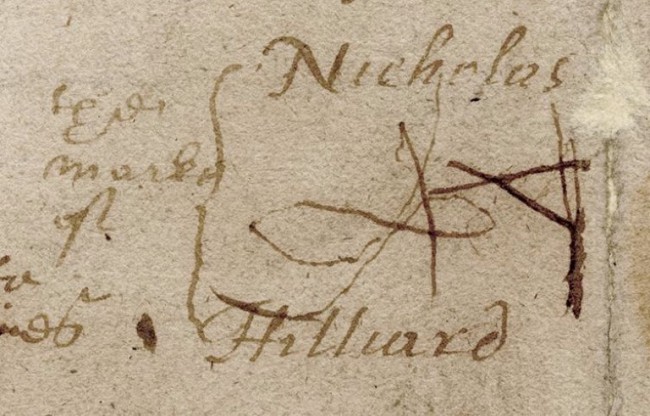

There are no substantive differences between the original text and the register copy; save for some minor variations in spelling, the same bequests may be found in both manuscripts. What sets the two documents apart is the fact that, in the original version, Hilliard – apparently unable to sign his own name – instead shakily has provided his ‘marke’: an ‘N’ superimposed on an ‘H’ in a manner reminiscent of the monogram seen on some of his miniatures. It is the ‘marke’ of someone no longer in control of the pen. As such, it provides a stark, and poignant, contrast to the carefully controlled precision which was – and is – a hallmark of Hilliard’s miniatures.

Close-up of the ‘marke’ of Nicholas Hilliard

Ruth Selman, Early Modern Principal Records Specialist at The National Archives, chanced upon the original version of the will just as my new book, Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist, was on the verge of being sent to press and generously alerted me to her find. It was a ‘stop the press’ moment and I am pleased to say that, after spending a delightful morning in Kew examining this extraordinary manuscript with Ruth – surely one of the last objects Hilliard touched – I was able to incorporate discussion of it in my book, along with a colour photograph of the ‘marke’ with which Hilliard attempted to sign it.

Book cover of Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist by Elizabeth Goldring

I have had the privilege over the years of studying many 16th- and early 17th-century manuscripts in archives throughout the UK, Continental Europe, and the United States. But rarely, if ever, have I felt such an immediate, and visceral, connection to the subject of my research as when holding the original version of Hilliard’s will in my hands.

Dr Elizabeth Goldring is an Honorary Associate Professor at the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick, and is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society.

You can hear her discuss the wide range of Hilliard-related manuscripts in The National Archives, on Tuesday 7 May 2019 at 13:00 at Kew (click here to book tickets).

A sample of these documents, including the original version of Hilliard’s will and the Great Seals he designed for Elizabeth I and James I, will be on display. Copies of Dr Goldring’s new book, ‘Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist’, will be available for purchase and signing in the bookshop.