On December 6 1918 the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) publication ‘The Common Cause’ declared:

The good feminist should now be trying to get good feminists returned to Parliament. [ref] The Common Cause, 6 December 1918. [/ref]

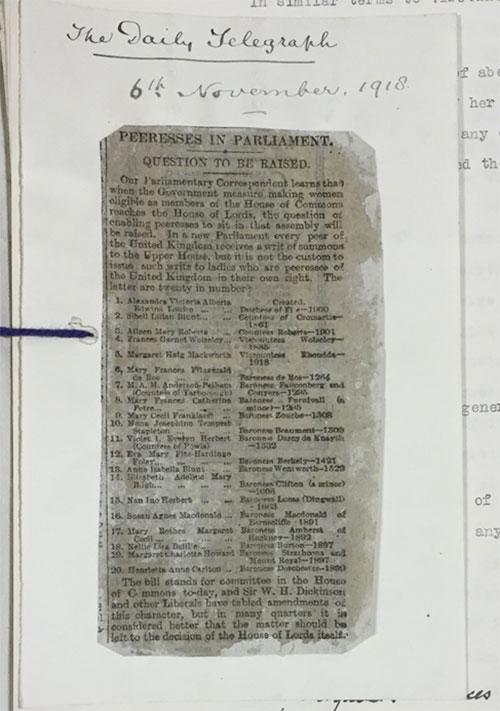

Discussion from 1918 regarding the right of women to sit in House of Lords, 1918 – 1919. Reference: LCO 2/388.

On 21 November 1918, the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act received Royal Assent: this enabled women to become Members of Parliament for the first time – you can read more about this in my colleague Katie’s blog post.

The opening up of the electorate in February 1918 to some women voters for the first time naturally triggered a conversation about female parliamentarians.

Reading parliamentary debates from this era, they seem to be dominated by the argument as intellectually won; if women could vote, surely they could stand for office? The foundations of the struggles for the vote were essential to the ease of this next victory (despite the attempted reassurances of suffrage campaigners to anti campaigners that one did not necessarily mean the passing of the other.)

The caveats around property qualifications and age restrictions did not apply. The cabinet was very clear on the reasons for restricted female franchise: they did not want a female-dominated electorate. They assumed that the same would not be reflected in Members of Parliament. Indeed there has yet to be a 50/50 Parliament, let alone a female-dominated one.

However, similar debates about allowing women into the House of Lords fell short. It would take another 40 years for women to be allowed into the Lords under the Life Peerage Act of 1958. Despite this act giving women access to the House of Lords, it was not until 1963 that women could become hereditary peers.

Women as candidates

With the knowledge that a post-war election would soon be needed, the short bill was speedily passed, in time for the 1918 General Election.

An election date was set for just three weeks after the passing of the legislation. Despite the limited time women had to organise their election campaigns, 17 women took to the hustings. This 26-word Act of Parliament gave women the right to stand as MPs, on equal terms with men: a much shorter, but in many ways more radical, act than the Representation of the People Act.

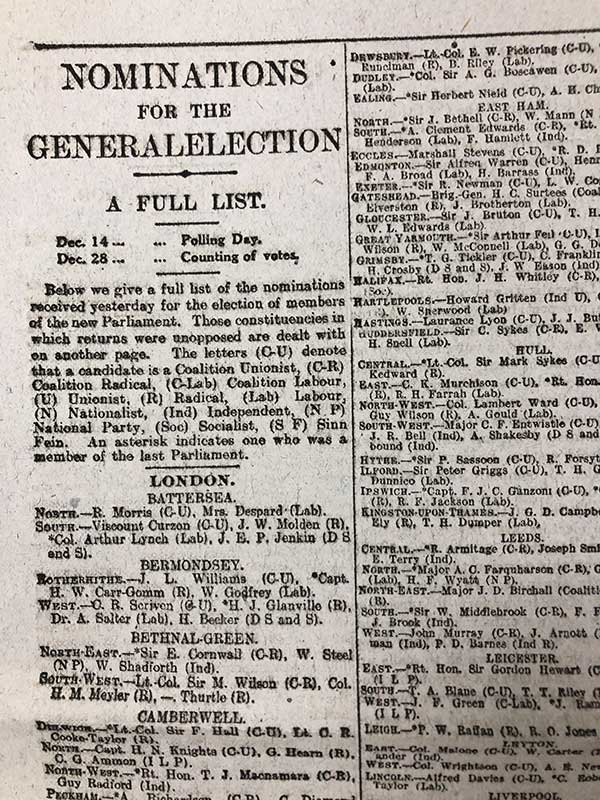

Full list of nominations for the December 1918 election. Reference: LCO 2/4412

These first 17 women to stand as parliamentary candidates were an eclectic range of individuals. Many have links to government records: through their war time service, their involvement in insurrections in Ireland, their continued work with post-war government bodies, or their encounters with the law from the Suffragette era.

The following women stood for Parliamentary seats in 1918:

Alice Lucas

Alison Vickers Garland

Charlotte Despard

Christabel Pankhurst

Constance, Countess Markievicz

Edith How Martyn

Emily Frost Phipps

Emmeline Pethick Lawrence

Eunice Guthrie Murray

Janet McEwan

Margery Corbett Ashby

Mary Macarthur

Millicent Mackenzie

Norah Dacre Fox

Ray Strachey

Violet Markham

Winifred Carney

Suffrage campaigners

Some of the first women candidates had been prominent in the militant and non-militant suffrage movements. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence stood as a Labour candidate for Rusholme, Manchester, while Christabel Pankhurst stood for the Women’s Party (a re-working of the Women’s Social and Political Union or WSPU) in Smethick. Both had been hugely significant in the pre-war suffrage campaigns. Christabel was considered one of the movement’s leaders, running militant campaigns from Paris during the most active years. Emmeline, and her husband Fredrick Pethick-Lawrence, had financially underpinned the militant WSPU and had gone to prison repeatedly as part of their fight.

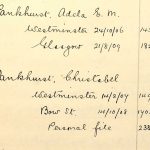

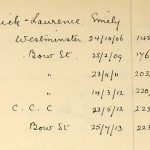

- Christabel Pankhurst, as listed in the Home Office index of Suffragettes arrested, 1906-1914. Reference: HO 45/24665. This has been made searchable online by Ancestry, in association with The National Archives: England, Suffragettes Arrested, 1906-1914

- Photograph of head & shoulders of Miss Christabel Pankhurst, 1910. Reference: COPY 1/550/238.

Alternatively, Charlotte Despard was an active suffragette, who broke away from the Pankhurst’s WSPU to form the militant but non-violent Women’s Freedom League (WFL). Home Office records show their pre-war arrests in the suffrage campaigns; now these women were fighting to influence politics from inside Parliament. To be what they had always truly wanted to be: ‘law makers, not law breakers’.

- Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, as listed in the Home Office index of Suffragettes arrested, 1906-1914. Reference: HO 45/24665.

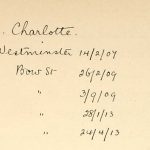

- Charlotte Despard, as listed in the Home Office index of Suffragettes arrested, 1906-1914. Reference: HO 45/24665.

Suffragist Ray Strachey, at the time parliamentary secretary of the NUWSS, also stood as an Independent parliamentary candidate for Brentford and Chiswick. You can learn more about these women through Suffrage scholar Elizabeth Crawford’s blog series. Suffrage societies had previously developed fighting funds to support pro-suffrage candidates, and many rallied around female candidates. Controversy ensued when women were asked to stand under their husband’s names, as in the case of trade unionist Mary Macarthur.

Women as parliamentarians (almost)

The vote was not announced until after an agonising two-week wait because of the many men in the process of being demobilised overseas. Despite the limited time women had to prepare their election campaigns, one woman did win her seat: revolutionary, nationalist, suffragette and socialist Constance Markievicz. Contrary to popular opinion, Constance was the first woman elected to the British House of Commons; however, as a Sinn Féin politician, she did not take her seat and was in prison at the time of her election. It is interesting that it was the most radical of the 17 women – arguably far more so than most suffrage supporters – who had become the first woman elected to the Houses of Parliament. (Although, as Dr Mari Takayanagi argues, there were questions over her legitimate candidacy.)

Despite the lack of women elected to Parliament after this significant election, Ray Strachey noted that the absence of women in Parliament seemed much less important than it had been before, as ‘every member there knew that he owed his election to the votes of women as well as men’ [ref]’The Cause’: A Short History of the Women’s Movement in Great Britain, Ray Strachey. 1928 [/ref] The nature of parliamentary politics had changed by the very allowing of women voters and Members of Parliament.

- Countess Constance Markiewicz, from Wikicommons

- Nancy Astor takes her oath and her seat, as the first woman to sit in the House of Commons, as documented in the Illustrated London News, 6 December 1919. Reference: ZPER 34/155

The women that followed Constance’s election were quite different in their pattern. The first three had already links to politics through their husbands – each, for different reasons, taking her husband’s seat. Indeed, this was the case with Nancy Astor in 1919. She was the first woman to be elected and take her seat: she served in as a member of the Conservative Party in Plymouth until 1945.

Many of the key players from the suffrage movement did not become prominent in parliamentary politics – as Sylvia Pankhurst wrote in her history of the suffrage movement: ‘The fight of the pioneers had been waged for generations yet unborn.’ [ref] The Suffragette Movement – An Intimate Account Of Persons And Ideals, E. Sylvia Pankhurst. 1931, p. 608 [/ref]

Election spread in the Illustrated London News from 1931, noting ‘there are more women in Parliament than ever before. In 1922 there were only two.’ ZPER 34/179.