One of the most important things that an archivist or librarian does when cataloguing a map or plan is to state which place or area it shows. One reason for this is that nearly everyone who decides to look for a map wants to find one that shows a specific place.

Naming or describing the area covered by a map is not always an easy task, for various reasons. The names, spellings and boundaries of places have often changed over the centuries, just as landscapes themselves have changed (for instance, through urbanisation). Printed maps made during the 19th and 20th centuries often show seemingly arbitrary rectangular areas of land, rather than single, identifiable places. [ref] 1. In many parts of the world, particularly in Europe and Asia, most places – including intermediate-level administrative units such as counties – have irregular boundaries. In other areas, such as parts of North America, straight-line boundaries are common. [/ref]

In some cases, it is not just difficult to state what place a map shows: it’s difficult to work it out, too. Not all maps have clear and unambiguous textual components, such a title or plenty of place names, to help identify the area covered. Although many maps held in archives have accompanying paperwork that may aid identification, others do not.

On rare occasions, a map has even been misidentified as depicting one place when it actually shows another. In today’s blog post, I look at two examples where government departments seem to have made this kind of mistake about maps among their records.

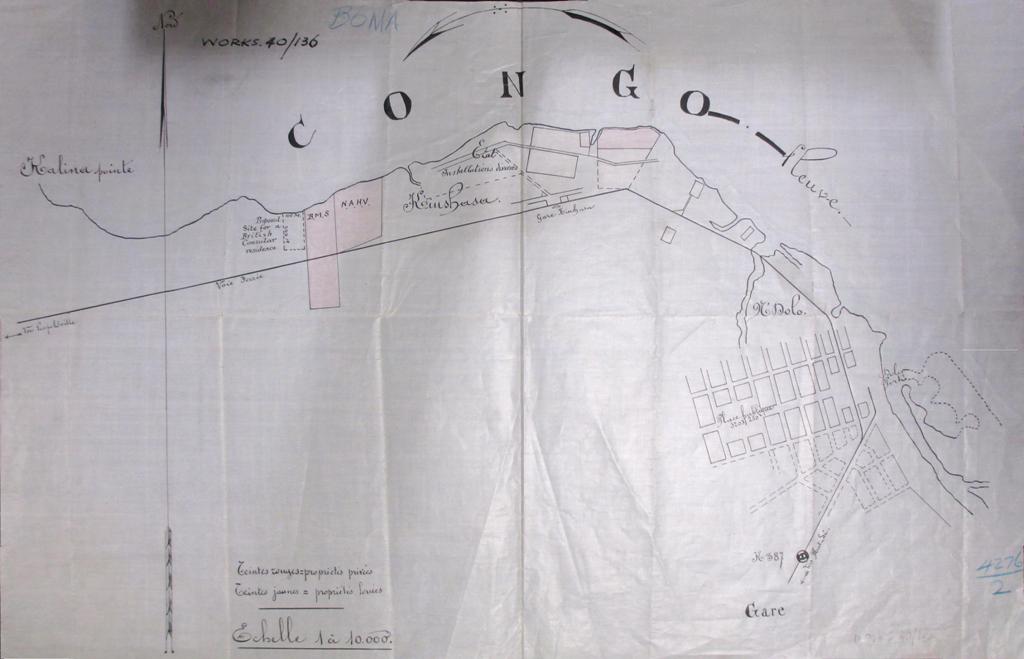

Map showing the proposed site for a British consular residence, probably dating from the early 20th century (Reference: WORK 40/136)

Where was the new consulate?

The sketch map above [ref] 2. WORK 40/136 [/ref] comes from a set of plans and drawings of British embassies, consulates and related buildings in other countries. These records were accumulated over many years by the Ministry of Works and its predecessors.

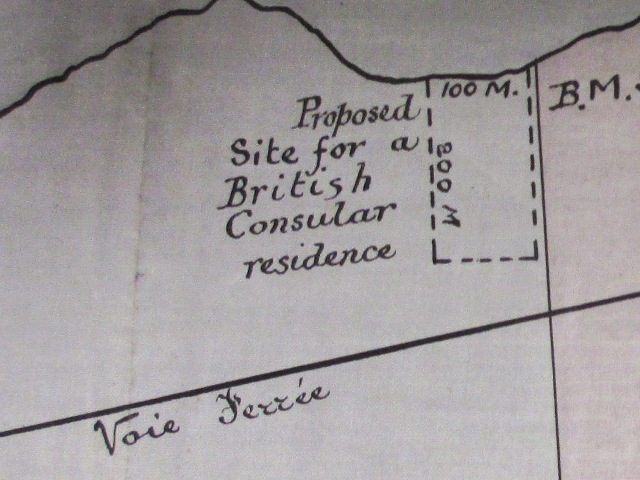

The map is labelled with the place name ‘Boma’ in blue pencil. It was originally filed with a set of architectural drawings for a British consular residence in that city, which was the original capital of the Congo Free State, later called the Belgian Congo. The map was also listed under Boma in the Ministry’s card index to its collections of drawings.

We now know that this map does not depict Boma. It actually shows the proposed site for the consular residence in Léopoldville, which took over from Boma as the capital of the Belgian Congo during the 1920s. There are several clues allowing the place to be identified as Léopoldville, notably the place names Kalina, Kinshasa and N’Dolo, and the curve of the River Congo, which forms the city’s northern boundary. Not only that, a small arrow on the left-hand side of the drawing, pointing westward to the more developed area of the city, is actually labelled ‘Vers Léopoldville’.

In 1966 the old colonial name Léopoldville was changed to Kinshasa (previously the name of a district within the city, and before that the name of a village in the area) [ref] 3. I told you place names could be complicated. [/ref] as part of a government drive to adopt more ‘authentic’ African place names. The name of the country itself has changed several times: once known as Zaire, it is now called the Democratic Republic of Congo [ref] 4. DR Congo is a separate country from the Republic of Congo (formerly French Congo), which lies to the north-east of DR Congo. The boundary between the two countries lies in the River Congo, after which both countries are named. [/ref].

A Spanish fort

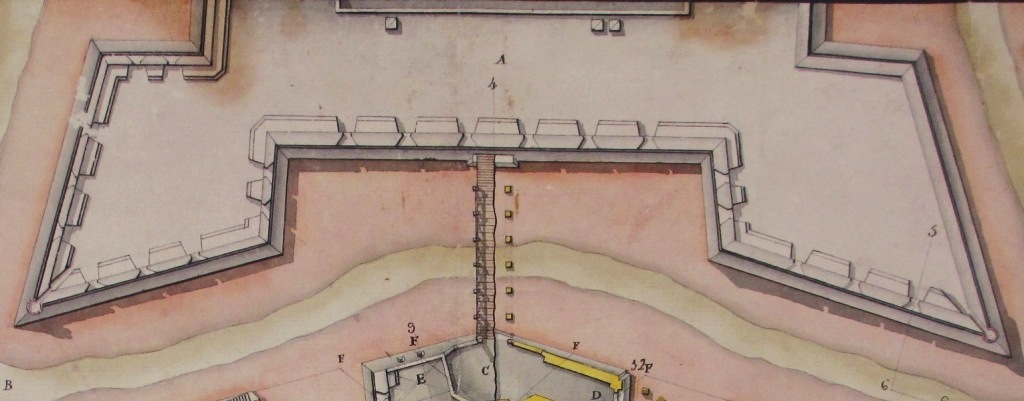

This Spanish-language plan [ref] 5. WO 78/1017/4/37 [/ref] comes from the War Office map collection. It bears the date of 22 February 1763 and shows part of a fort in a place called San Agustín.

Some years ago, when we were converting entries from our hard-copy map catalogues into descriptions suitable for the online catalogue [ref] 6. This conversion is an ongoing task. Some of our maps are still described in more detail in paper catalogues than in our online catalogue. [/ref], the question arose of where this San Agustín was. We found that two separate descriptions existed for the plan: one placing the fort in Spain [ref] 7. Geraldine Beech, Maps and Plans in the Public Record Office. Part 4, Europe and Turkey (TSO, 1998), entry 4367. [/ref] and the other placing it in Florida. [ref] 8. P A Penfold, Maps and Plans in the Public Record Office. Part 2, America and West Indies (HMSO, 1974), entry 2353. [/ref]

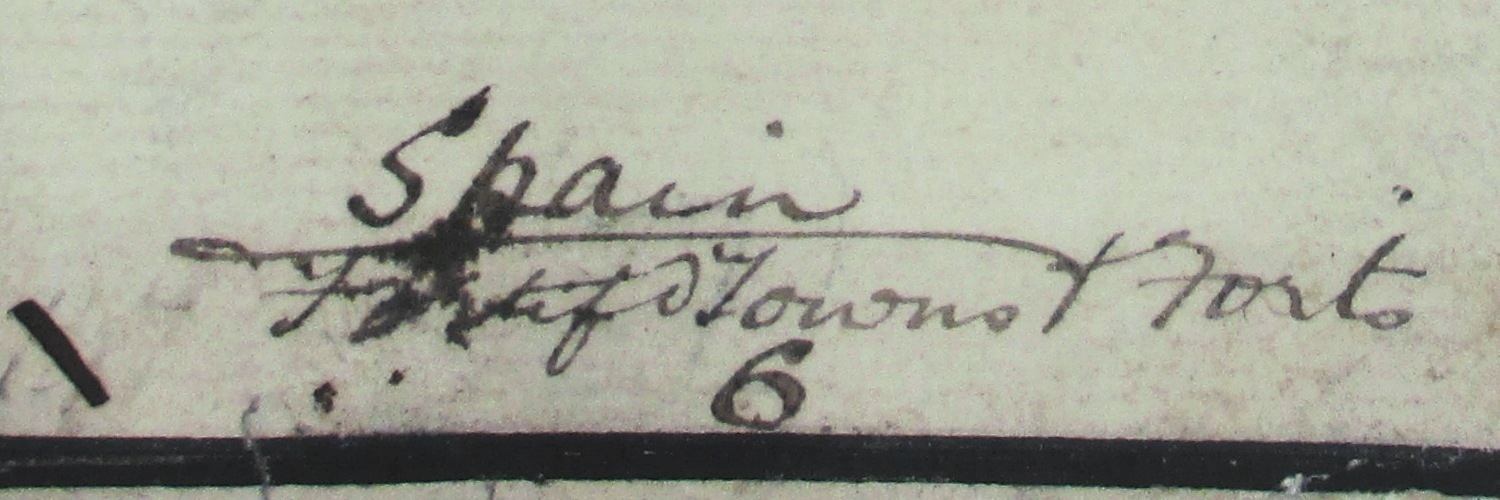

The War Office’s librarians evidently thought that the fort was somewhere in Spain. They wrote the reference number ‘Spain/Fortified Towns & Forts/6’ onto the plan and kept it as part of a set of maps and plans showing fortifications in Spain and Portugal.

We now realise that the Florida identification is almost certainly the correct one. The full title of the map gives the place name as San Agustín de la Florida, now known in English as St Augustine, and the shape of the visible part of the fort seems to match that of the city’s Castillo de San Marcos.

The fort was built in the late 17th century when the area was a Spanish colony. In July 1763, control of the region passed to the British as part of its new province of East Florida. It is likely that this plan came into British hands at that time. The name of the Castillo was rendered into English as Fort St Mark. British control was short-lived, as the region reverted to Spanish control under the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

When Florida became part of the United States of America in 1821, the fort was renamed Fort Marion. The fort now holds the status of a National Monument of the United States and is officially known in English by its original Spanish name, Castillo de San Marcos.

![The plan’s title: ‘Plano del frente principale del Castillo de Sn. Agustín de la Florida …’ [‘Plan of the principal front of the Castle of St Augustine of Florida …’].](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/01165018/wo-78_1017_4_37-title.jpg)

As far as the ‘Boma’ map goes the railway line and railway station would lead away from Boma (a former slavery post) and to a larger place. The question would be why would we have a new consulate when we already have one at Boma (see Discovery). However I doubt it is dated early 20th century (it looks more 19th century), it doesn’t look like 20th century and I believe that in 1903 Sir Roger Casement was the British Consul in the Congo who was sent into ‘the interior’. I am sure that Treasury would be asked for approval to the building. I am sure that the Foreign Office List would confirm the date one way or another.

As far as the Florida map goes it could be argued that it was part of the Spanish Empire but doesn’t excuse the error. The moto should be don’t assume the description is correct if it doesn’t seem to fit it probably is wrong.

Thank you for your comment, David. I’m sure that a researcher who took the time to trawl through other potentially-relevant sources, such as those that you suggest, would uncover some further useful information.

Whether or not the mistakes of the past are excusable is a matter of individual judgement. Speaking for myself, I am willing to forgive government officials from years past the occasional instance of human error.

The word “boma” was used quite widely to mean a colonial headquarters – perhaps that helps the explanation? In other words, Boma wasn’t a placename at all in this case, rather the name of a built, or proposed, feature?

Thank you for your comment, Graham, and for the ingenious suggestion. It’s only too plausible to think of one person referring to ‘a boma’ and another misinterpreting this as ‘Boma’ or vice versa.