There is a concept of life in Britain just before the First World War as the Indian summer of the Victorian world, a golden age when sunny days were as long as the dresses of ladies taking tea at country house parties, and, as Boris Pasternak wrote in The Last Summer, a time when ‘life appeared to pay heed to individuals’.

What was life really like then? An original contemporary source gives details that help to give a truer picture of how people from a wide cross-section of society lived.

The Valuation Office survey made around 100 years ago was a property valuation for tax purposes; it was such a comprehensive survey of land and buildings that it was dubbed a New Domesday. It has a wealth of detail about people and places, giving us a unique ‘snapshot’ of property and society in Edwardian England and Wales. Maps serve as the means of reference to more than 95,000 Field Books which contain descriptions of some nine million individual houses, farms and other properties.

Why and how was the survey carried out?

In the early 20th century much land was still owned by a privileged few, who often got richer as their land increased in value with no effort on their part. This was beginning to be seen by many people as a social injustice.

In 1909 the Chancellor of the Exchequer was David Lloyd George (who became Prime Minister in December 1916), after whom the survey is sometimes named. His Liberal Government’s so-called ‘People’s Budget’ introduced a new tax on any increase in land values due to the state rather than to landowners’ own efforts. First, a valuation was made of all land in the United Kingdom, to fix the base line from which increases in value would be calculated. Each property was given a plot number, unique within its income tax parish, which was written on the relevant map, and a description written in the related Field Book. The amount of detail varies but can give much information about the use and value of lands and buildings, and names of their owners and occupiers.

From grand estates to slums

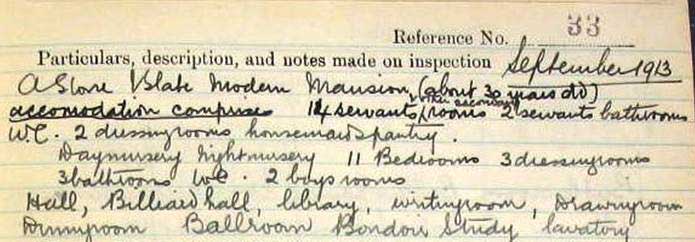

An example of a large estate was Bayham Abbey near Lamberhurst, Sussex, the Marquess of Camden’s ‘stone and slate modern mansion’ arranged to reflect the social status of its occupants. For the family there were 11 bedrooms, a billiard hall, library; writing, drawing and dining rooms; a study, boudoir, day and night nurseries, even a ballroom.

Page two of the Field Book entry for Bayham Abbey, Sussex (catalogue reference: IR 58/85764 plot 33).

Servants inhabited separate regions of the house: a servants’ hall, 14 servants’ bedrooms, housemaids’ and butler’s pantries, a laundry and a secretary’s office. Other ‘below stairs’ rooms you may find listed include scullery, china pantry, boot and lamp rooms. The rest of the estate had stabling for 17 horses, a garage, fire engine house, riding school, and even its own church for 150 people.

If the survey provides plenty of evidence of how the upper classes lived, with descriptions of grand country houses, there are contrasting descriptions of homes at the other end of the social scale, too, from rural hovels to city slums. Information written in Field Books varies between districts and surveyors, who might write very little when faced with endless rows of houses.

Crown Street in Camberwell appears on Charles Booth’s poverty map as inhabited by the ‘lowest class’ (image courtesy of London School of Economics)

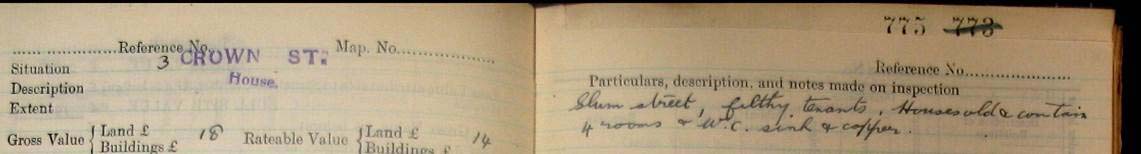

Looking at Charles Booth’s poverty maps of around 1900 showing the poorest areas of London, we find part of Camberwell looked rather black, which meant that Booth found these streets the hangouts of the worst criminal classes. How does this appear in the Survey?

The Field Book entry for 3 Crown Street, coloured black in the Booth survey, suggests that the surveyor did not want to spend much time in this area; he simply noted ‘slum street, with filthy tenants’. It is rare for a surveyor to comment upon inhabitants, and he did so because it affected the value – a mere £90 (compared with £71,275 for Bayham Abbey). The 1911 census entry for this property shows the four rooms divided among two families, with 15 people crowded in one small house.

Part of the Field Book entry for 3 Crown Street, Camberwell (catalogue reference: IR 58/27892 plot 775)

Online research tools

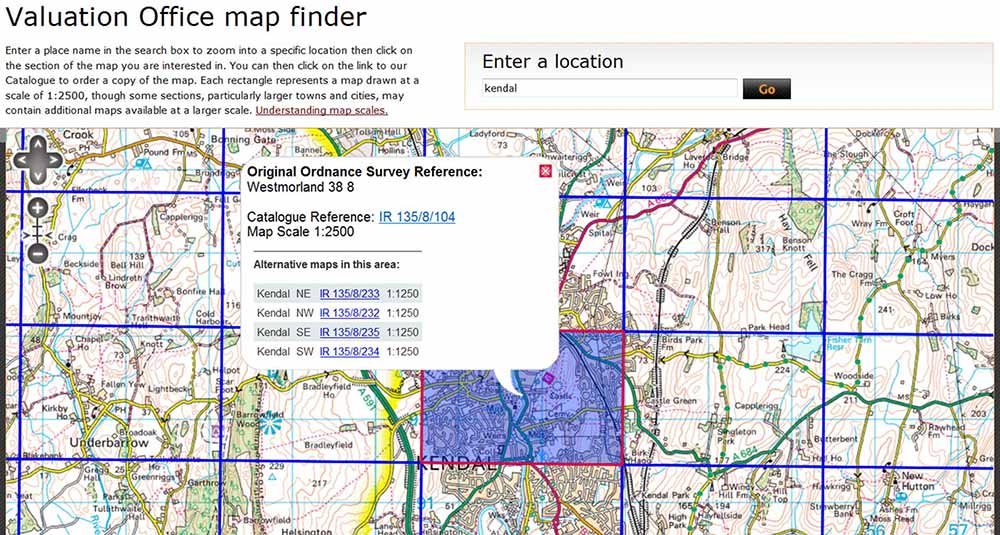

Now access to this complex set of records is made easier by innovative tools created by our Systems Development Team, which use modern online maps to provide a simple way to identify and order an original map, from among 50,000 Valuation Office Survey maps, without having to visit The National Archives. Use the Valuation Office map finder tool to find the document reference for maps in England and Wales, and the new tool to find maps of London.

For instance, a search on Kendal in the Valuation Office map tool shows that the document reference is IR 135/8/104 for the original map showing part of the town centre, with the railway and the castle. When using the tool yourself, you can click on the reference IR 135/8/104 which links to the description of the map in our online catalogue, where you can order a copy.

The Valuation Office map finder in action, showing results for a search on Kendal

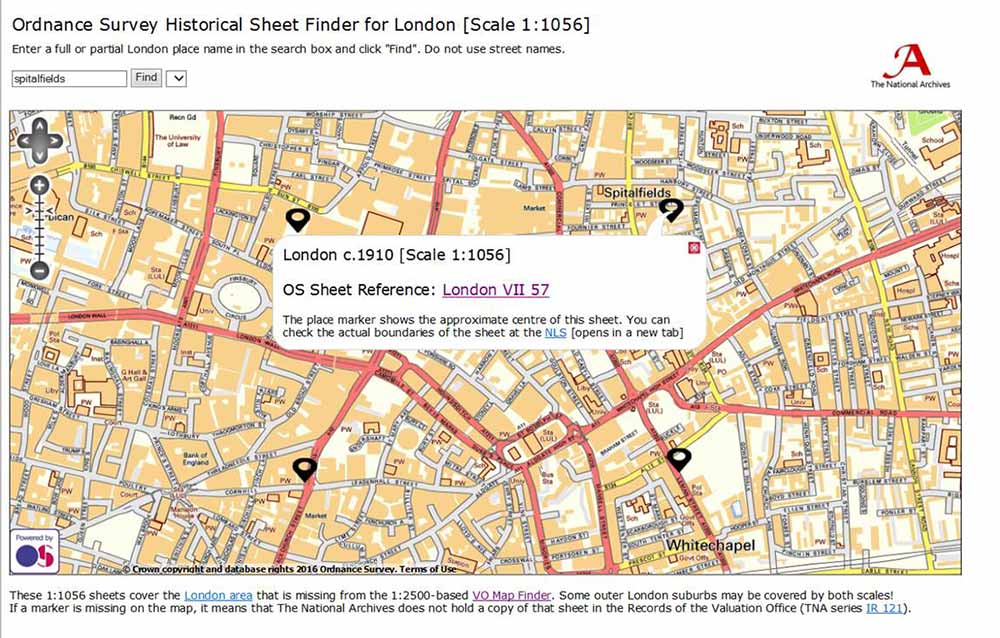

Use the new London Valuation Office map tool to find document references for original maps of places in London. This was previously made particularly difficult by the intense coverage of London using many maps at much larger scales than were needed in the provinces.

London example: Jewish East End

The new London Valuation Office map tool presents results for the area of Spitalfields in the Jewish East End

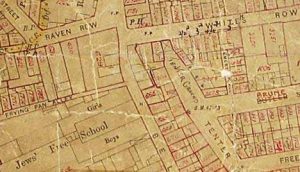

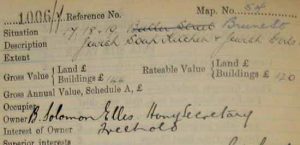

This is part of an original map of the area shown in the London map finder tool. It shows part of Spitalfields, in the area of Frying Pan Alley and the Jews’ Free School to the west, with a ‘tenter ground’ handwritten indicating an area for drying cloth, while in Brune Street plot 1006 is revealed by the Field Book entry to be a Jewish soup kitchen which the photograph shows had opened in 1902 – the Jewish date is also given – and only closed in 1992, being refurbished as bijoux flats for City workers.

- Part of the Valuation Office map showing Spitalfields (catalogue reference: IR 121/20/25)

- Field Book entry for soup kitchen (catalogue reference: IR 58/84296 plot 1006)

- Photograph of the former soup kitchen (image from Jewish East End website)

Thomas Hardy in his Dorset home

The survey can also work in conjunction with other sources such as the 1911 census, to give us a clearer picture of who lived in a house and what it was like.

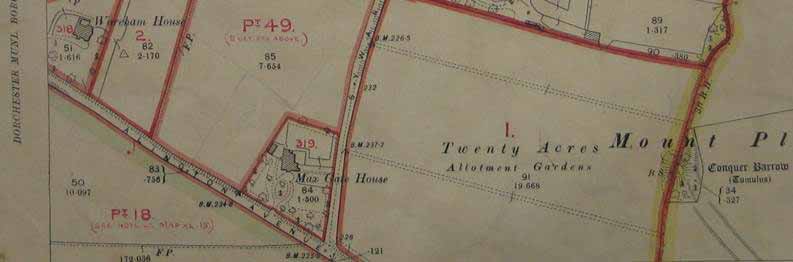

For example, Thomas Hardy, the writer of the ‘Wessex’ novels, was originally an architect, and designed his own house, Max Gate, near Dorchester. The map shows it with the number ‘319’ handwritten in red.

Part of the Valuation Office map showing Max Gate House (catalogue reference: IR 125/2/422)

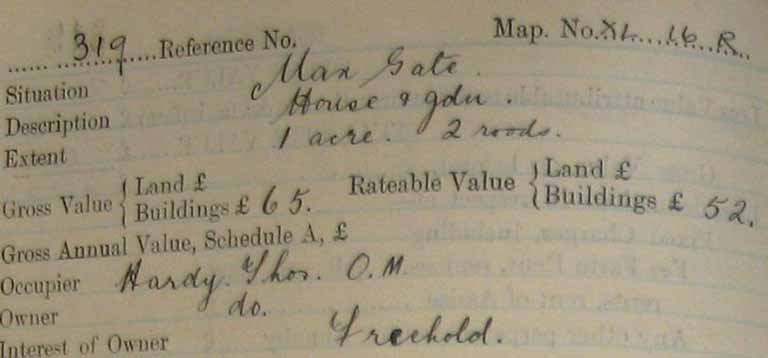

Page one of the Field Book entry for Max Gate (catalogue reference: IR 58/27892 plot 319)

Hardy is listed in the Field Book entry as owner and occupier of the house – ‘OM’ are not initials, by the way, but refer to his Order of Merit.

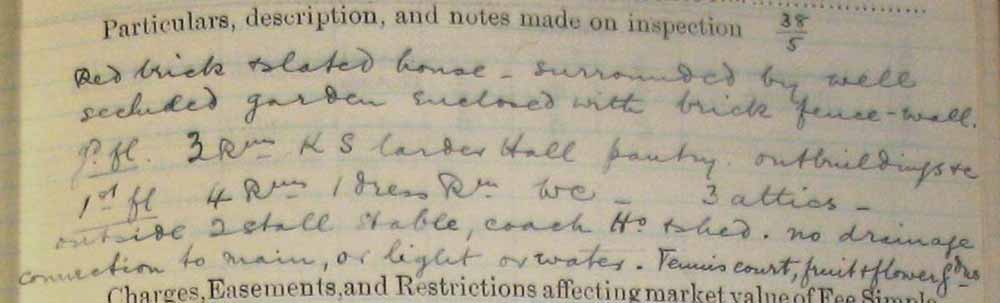

The visiting surveyor noted a red brick slated house with four bedrooms and three attics, surrounded by a well secluded garden with a tennis court, fruit and flower gardens, but no mains drainage, piped water or electricity.

Page two of the Field Book entry for Max Gate (catalogue reference: IR 58/27892)

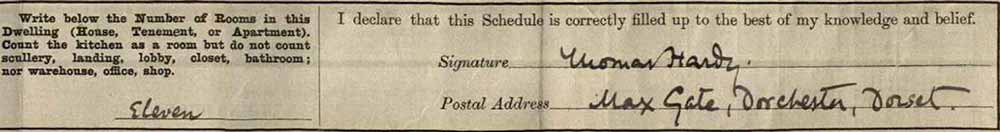

If we compare this Field Book description for Max Gate with its entry in the 1911 census, where for the first time the number of rooms in the house was given, we find that Thomas Hardy – who would have filled in this form himself – counted 11 rooms.

1911 census entry for Max Gate (catalogue reference: RG 14/12381).

The census shows Hardy, ‘author of books’, with his first wife Emma, who was to die the following year and inspire some of his most famous poetry. The Valuation Office survey records, along with other contemporary sources, can thus throw light on people and places at a particular moment in history.

1911 census entry for Max Gate shows Thomas Hardy and his wife Emma (catalogue reference: RG 14/12381)

Please note that Valuation Office Field Books can only be viewed at The National Archives. For more information on the Valuation Office Survey, its history, contents and how to access its information see the research guide Valuation Office survey: land value and ownership 1910-1915.

The original maps for London are expected to be placed online as part of a digitisation project called Layers of London based at the University of London‘s Institute of Historical Research.

Pasternak, not Nabokov, I think

Hi Chris,

Thanks for your comment. You are correct, and I’ve updated the blog.

Best,

Nell

As I am researching an entire village, I have several questions.

Would the plans and books be all in one place or in different volumes? (Are they done by parish, as with the Tythe Maps?)

Would I need to order a copy of every household, or do several households appear on the same page?

How much does a copy of the map and book covering the area of the map cost?

EG: The map I need is IR 127/9/755 and, obviously, I don’t know the rest of the information till I see the map but I know the parish is Weasenham St Peter. Can I apply for a copy of that map and, if so, how much would that cost me?

Can I apply for the book to go with that plan or do I need to wait for the plan to arrive and then apply for each household, or is each building in the same document? (Many buildings housed several households.)

It may be cheaper to come to the National Archives but is photography allowed?

Sorry for the questions but this appears to be an amazing source!

Many thanks.

Glynn

Hi Glynn,

Thank you for your comment.

We’re unable to help with research requests on the blog, but if you go to our contact us page: http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/contact/ you’ll see how to get in touch with our record experts via phone, email or live chat. You can also check out our research guide on the Valuation Office survey: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/valuation-office-survey-land-value-ownership-1910-1915/

There’s information on accessing and copying records here: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/about/visit-us/researching-here/accessing-and-copying-documents/

I hope that helps.

Nell