One of the best parts of my job is stumbling across unexpected items buried within our collections. Recently, a colleague told me about drawings of an early 19th century crime scene; I couldn’t resist taking a look for myself.

In 1837 a stonemason called James Gibbs was convicted of sheep rustling and sentenced to transportation for life. James protested his innocence and his friends sent letters of support to the Home Office.

Accompanied by the letters were four colour drawings of the local area and the scene of the crime. Altogether they tell us much about the inhabitants of the town and are a visual representation of the fact that James could not have been responsible for the crime.

The crime scene

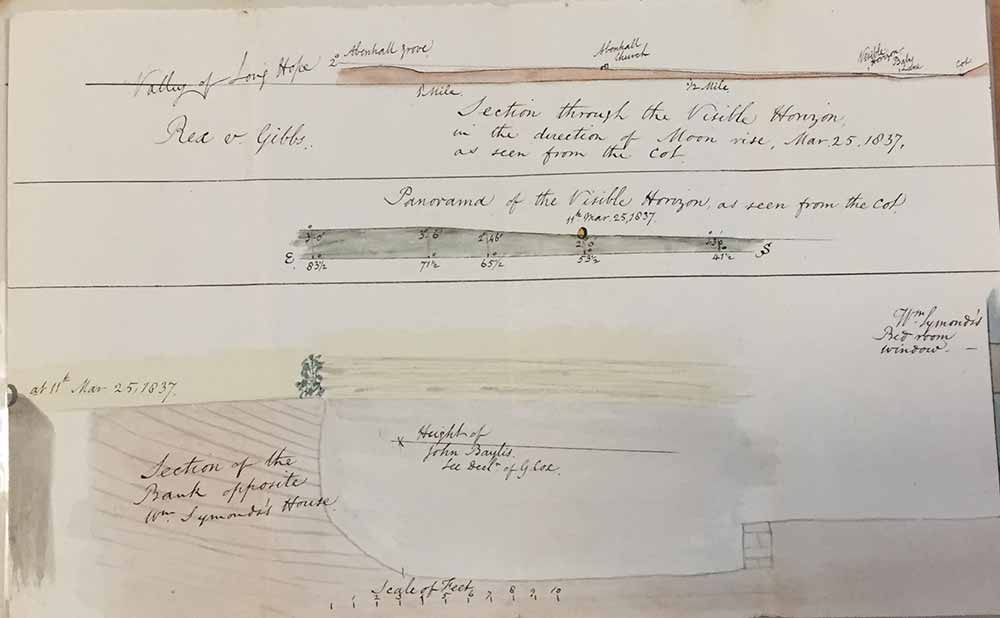

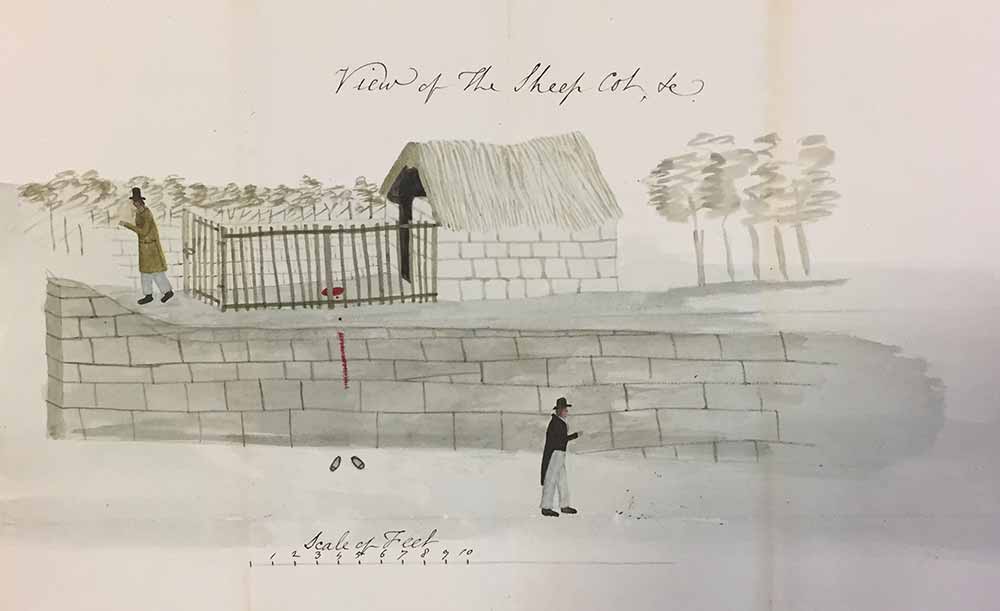

The details included in the drawings are staggering. The first drawing is a view of the sheep cot in question, including the trail of the sheep’s blood on the outside wall of the enclosure.

You may wonder what the significance of the blood is – why would a trail of blood be unusual in a sheep rustling case? The answer can be found within the accompanying bundle of petitions and evidence; the witnesses alleged that James dragged the sheep over the fence and wall before putting it back in the cot when he was disturbed. Surely then there would be blood on the fence as well? This was an argument used by petitioners to discredit the witness testimony.

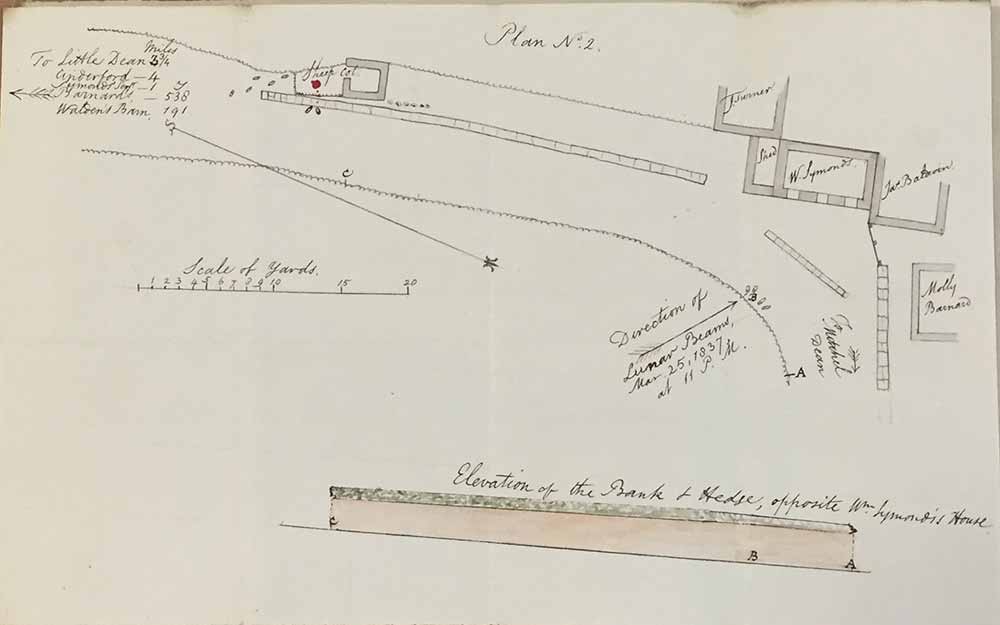

Other drawings detail what would have been visible in the moonlight by the witnesses at 23:00 on 25 March 1837. They show that because of the angle of the lunar beams, and the height of the bank opposite one of the witness’ houses, an alleged accomplice of James could not have been spotted.

Drawing showing what would have been visible on the night of the crime by the lunar beams (catalogue reference: HO 17/66/20)

The town

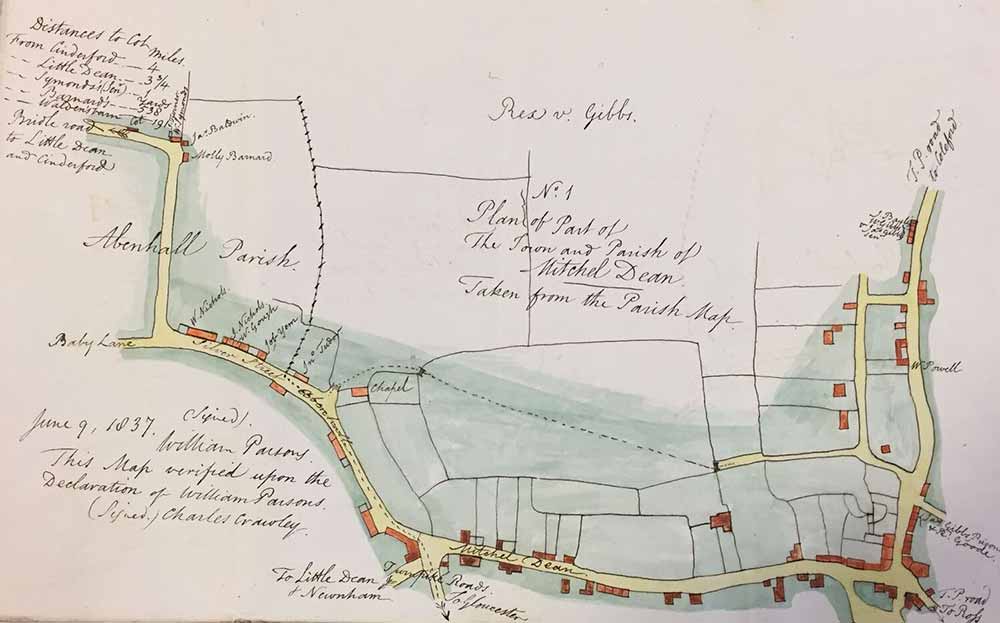

The document not only tells us about the crime that James was accused of, we can additionally learn about the town of Mitchel Dean, [Mitcheldean] Gloucestershire, in the mid-19th century.

The crime took place before the first census in 1841 so the only way for us to know about the town and its residents would be through parish records held locally. Yet, from the letters sent on James’ behalf held at The National Archives we know that the witness Elijah Symonds was staying at his brother William’s house on the night of the crime. Elijah usually resided with his father but on the night of the crime left his father’s house at 22:00 with a friend and arrived at William’s house at 23:00; taking an hour to walk a mile. This seems unlikely especially as petitioners stated that it was snowing on the night of the crime in March 1837.

Drawing showing the scene of the crime in the context of the surrounding buildings (catalogue reference: HO 17/66/20)

From the images we can see where houses were situated in the parish and where the key players in the saga lived in relation to the crime scene. The drawing above, titled ‘Plan No.2’, shows us that the scene of the crime was surrounded by not only the house occupied by William Symonds but also properties where a J. Turner, Jasper Baldwin and Molly Barnard resided.

The final drawing submitted shows where these people lived in relation to James Gibbs and other townspeople. For local history a plan like this could be invaluable; not only can you trace where local families lived but also the built environment of the town in the 1830s.

Plan of part of the town and parish of Mitchel Dean [Mitcheldean], Gloucestershire (catalogue reference: HO 17/66/20)

Ordinarily when receiving a box of HO 17 petitions we would expect to find a bundle of letters for each convict, they are quite text-heavy and can be difficult to read if you aren’t used to the handwriting of the period. You can find out more about what the records ordinarily contain from some of my colleague Briony’s blogs and from our research guides on criminals and convicts and criminal transportation. Suffice to say we wouldn’t expect to see detailed drawings of a crime scene.

James Gibbs’ petition is a great example of what you can find buried within our archival material held here at The National Archives. HO 17 isn’t a record series known for being particularly visual so it goes to show that it is worth ordering up records and browsing through them as you never know what you may find.

In case you are wondering, James’ sentence was initially reduced to 14 years transportation and he was later pardoned. The drawings were a success!

I love wading through old archives and documents. What a great blog, thanks, Suzanne.

Fascinating. Thanks!

That is so neat! And what a taste of the different circumstances of the day… Drawings, sheep blood, walking pace, weather, moonbeams! A true sleuthing feat 🙂