In 1829, John Travwicks, described as ‘a quiet inoffensive man’, was sentenced to transportation for life, leaving behind a loving wife and three children who were left in a ‘wretched and deplorable situation’.

John had served his country in the Navy and appeared well-respected in his community, apparent in the 25 signatures in support of his petition for mercy. Nevertheless, John was refused and banished to Australia. Despite the distance, John’s love for his family never faltered as he declared, ‘i shall have no hopes of ever seeing England any more’ but that ‘my h[e]art i[s] there’ (sic).

As with many other stories in the ‘With Love‘ exhibition, love could be found in unusual places. John’s love letter to his wife, Lydia, was found attached to a petition appealing for his freedom to return home. Separated for 20 years, the petitions of John and Lydia reveal a story of loss, longing and love which defied the odds.

Why was this man given the most severe life sentence?

John and Lydia argued that his conviction was a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. John was sentenced at the Old Bailey for stealing stationery from a wharf. However, the physical property was not actually carried away due to it being ‘four or five hundred weight’ but had been ‘removed about two feet’, and as John was the only person on the premises, he was found guilty. The Travwicks also emphasised the unfairness of the trial taking place at 9 o’clock at night when they ‘did not understand anything about wanting a council’.

John maintained his claim of innocence throughout his sentence, and his wife in her multiple petitions said, ‘If I know he was guilty I would not ask so great a favour’. Even 18 years later, his prior employer wrote to the Home Office stating that ‘I never had any reason to suspect him’.

A self-proclaimed innocent man, he was ripped from his native shores with no hope of freedom. Degraded, he endured his flesh being cut by a hundred lashes from additional punishments in Australia. How long could his faith in God, humanity, and the love for his wife last?

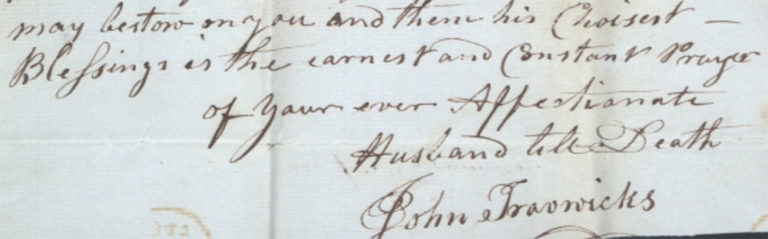

Loss, longing and love: ‘Your ever Affectionate Husband till Death’

Hardship had characterised the best part of John’s life, but it did not harden his affection towards Lydia and their family. In 1847, John wrote of news that he expected to be granted a pardon but stated that ‘if I obtain it will be of little use to me’ as it was conditional that he would not return to Britain. Admitting to having a ‘hard struggle to obtain a Living’, he maintained, despite his suffering, that if it was allowed ‘i should have come [home] had it been without a Shirt’.

John’s letter did not expand further on his suffering, but instead focused on his attempts to be part of his family’s life from afar. John wrote to Lydia, ‘why do i complain of my Trouble to you that have so many of your own’, and praised her for acting as ‘both father and mother to our dear Children’. His letter also refers to correspondence with his children, suggesting they maintained a relationship despite his wish that his son ‘may Prove a better father and husband than his unfortunate father’.

Central to his letter to his wife was his faith in their eternal bond despite their separation. Many convicts with a life sentence, and no prospect of legal return, chose to remarry in Australia and start their life anew. However, John did not accept the finality of his banishment and wrote to Lydia that he was pleased ‘those foolish suspitions where removed from your mind’ regarding his love for her, and assured her that he would remain ‘your ever Affectionate Husband till Death’ (sic).

The bittersweet chance of reunion: ‘The grief we have suffered no tongue can tell’

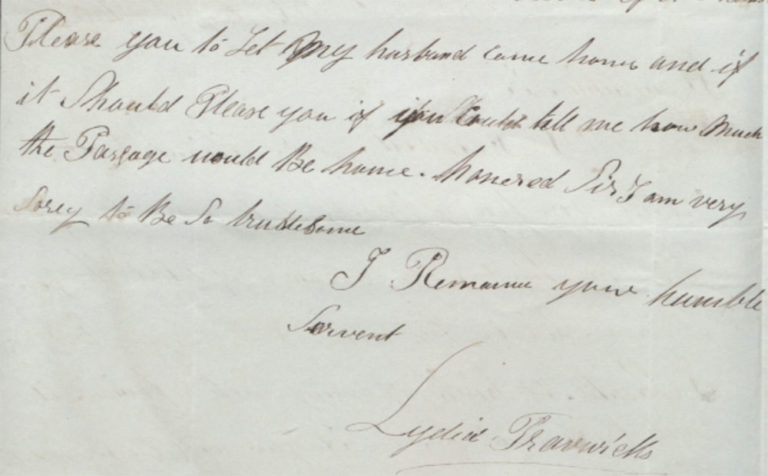

A conditional pardon was a sign of hope that John’s sentence could be changed, and his letter set into motion a campaign by Lydia to appeal for a full free pardon. Lydia presented her own emotional petition, which accounts her struggle to bring up her children alone, initially not knowing ‘how to get them a bit of bread’.

During John’s transportation, one of their children died, but despite this grief, Lydia displayed her worthiness for consideration by alluding to her good mothering skills, pointing out that none of her children had fallen into crime and were instead ‘eating the Bread of honesty.’ Her powerfully emotive petition, in which she wrote ‘the grief we have suffered no tongue can tell’, struck a chord with the Home Secretary, who answered her petition by offering her free passage to Australia to reunite with John.

Although ‘truly thankful’ for the offer, Lydia refused and instead requested an exchange of her free passage for John’s. Lydia’s case gained the attention of a parish minister who joined her petition, arguing that she was too old for the voyage, especially to join a man she had been estranged from for 20 years, an action ‘none interested for her cared advise’. Lydia vowed she would be ‘Heartly glad to embrace it if My Children where Young that I could lead them’, but she could not bear to never see her children again, especially as her daughter’s husband had died a year prior in a wharf accident leaving her and her grandchildren dependent on her.

An exceptional petitioner: Lydia Travwicks

A free pardon for a convict with a life sentence was a near impossible feat. After 1823, the majority of convicts were pardoned on the condition they would not return to Britain. Lydia’s petition demonstrates her agency to use the power of the letter to defy the odds and build a case for her husband’s return. As well as attracting support from the parish minister, she convinced John’s old employer to offer him employment on his return and raised the necessary money for his voyage and sent it to Australia. Lydia also tracked down John’s employer who returned to England from Australia, who provided a positive account of John and wished also to ‘join Lydia Travwicks humble petition’.

In 1849, after eight petitions and 20 years after his transportation, John Travwicks was given permission to return to his native soil. Death not distance seemed to part the couple as their death certificates show that Lydia died in 1865 and John a year later, both being laid to rest in London, England.

Source: TNA HO17/113/17

This was a very moving account of lives in the 1800s well done.

There is a John Travwicks who was acquitted of a misdemeanour (unclear for what) where he was acquitted in January 1829 at the Central Criminal Court, see ‘Old Bailey online’.