On 16 August 1819, 60,000 people gathered on St Peter’s Field in Manchester to hear the famous Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt (1773-1835). Hunt was a prosperous gentleman farmer from Wiltshire, who had become a famous figure in the fight for political reform. The meeting on 16 August was part of a wider escalating radical campaign, designed to place increasing pressure on the government. The authorities were nervous, referring to Hunt and his fellow reformers as ‘the little Gang of evil Spirits’ who were bent on breeding disturbance and rebellion[ref]Quoted in Robert Poole, ‘“By the Law or the Sword”: Peterloo Revisited,’ History 91:2 (2006): 269[/ref].

Hunt, however, told the radicals to come to the meeting on the 16 August ‘armed with NO OTHER WEAPON but that of a self-approving conscience; determined not to suffer yourselves to be irritated or excited, by any means whatsoever, to commit any breach of the public peace’[ref] Henry Hunt, Broadside: To the Inhabitants of Manchester, 1819, Manchester Archives, GB127.Broadsides/F1819.2.F.[/ref]. On 14 August, after hearing a rumour that the magistrates had issued a warrant against him, he offered to surrender himself to the authorities in order to prevent them using it as a pretext for breaking up the meeting[ref] John Belchem, ‘Hunt, Henry [called Orator Hunt] (1773-1835), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/14193, accessed 15 August 2019[/ref].

Hunt’s attempts to ensure the demonstration was peaceful failed. The magistrates sent in the local yeomanry and soldiers to arrest Hunt and the other speakers and disperse the crowd. In the chaos and violence that followed, as many as 18 people were killed and hundreds more injured.

(Henry Hunt’s invitation to the people of Manchester and other Peterloo documents have been brought to life by actors in Archives Alive: Peterloo, a collaboration between The National Archives and Royal Holloway, University of London, supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund. All 18 videos are available to view on YouTube).

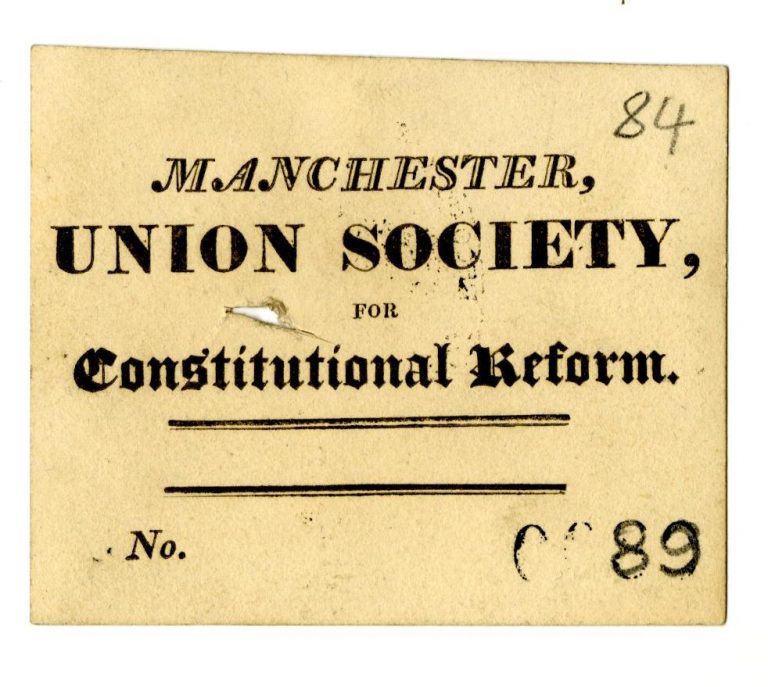

A card prodcued by the Manchester Union Society for Constitutional Reform, who helped organise the St Peter’s Field meeting Hunt spoke at in 1819. Catalogue reference: HO 40/10/2

‘Crime’ and Punishment

After the bloodshed, Hunt and nine others were charged with ‘unlawful and seditious assembling for the purpose of exciting discontent’[ref] John Belchem, ‘Orator’ Hunt: Henry Hunt and English Working-Class Radicalism (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), 118[/ref]. Hunt succeeded in getting his trial moved from Lancaster to York, where he felt the jury would be less prejudiced. He hoped that his trial would provide the opportunity to hold the authorities to account for the massacre, writing: ‘Some of the fools say I am going to be tried, but I am going to try the bloody Butchers of Manchester and I have not the least doubt that they will be all found guilty’[ref] Quoted in Poole, ‘By the Law or the Sword,’ 272[/ref].

After a two-week trial, Hunt was found guilty in March 1820 and sentenced to two and a half years in Ilchester Gaol. He used his time in prison to write a three-volume autobiography, as well as two volumes entitled To the Radical Reformers, Male and Female of England, Ireland and Scotland. His crusade against the poor conditions at Ilchester Gaol led to the governor being dismissed for gross misconduct.

Business ventures

Post-Peterloo, Hunt attempted to recover his lost personal fortune by launching several businesses which were shaped by his radical politics. The first of these was the production of a ‘Breakfast Powder’. Hunt advertised it as ‘a wholesome and nutritious beverage, made of prepared and roasted grain’. He also produced a ‘British Herb Tea’. Both of these products were designed as an alternative to taxed tea and coffee, which Hunt described as a ‘heating, deleterious, narcotic berry, the production of a foreign clime’[ref] Henry Hunt, ‘Suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act,’ in To the Radical Reformers, Male and Female, of England, Ireland, and Scotland (London: T. Dolby, 1821), 16[/ref].

An 1894 for Everett’s Blacking shoe polish from 1894. Somewhat more successful that Hunt’s business venture perhaps. Catalogue reference: COPY 1/115/439

He also created a ‘matchless blacking’ shoe polish, which led to countless satirical images of Hunt the ‘Blacking Man’. After one political opponent, Alexander Baring, made a jibe in parliament concerning Hunt’s business ventures, Hunt wrote him a letter thanking him for the free publicity, along with a complementary bottle ‘of my very best “matchless”’[ref] Henry Hunt to Alexander Baring, 14 February 1826, reprinted in Cobbett’s Political Register, vol. 68 (London, 1829), 602[/ref]. Even this business was connected to his radical interests: bottles were embossed with the slogan ‘Equal Laws, Equal Rights, Annual Parliaments, Universal Suffrage, and the Ballot’, while the vans used to distribute the product also served as hustings at meetings and floats at processions[ref] Belchem, ‘Orator’ Hunt, 269[/ref].

In Parliament and opposing the Reform Act?

In December 1830, he was elected MP for Preston. At the centre of his election campaign was his promise to help ‘the poor, the honest, and the industrious who live by the sweat of their brow’[ref] Preston Chronicle, 11 December 1830, quoted in Belchem, ‘Orator’ Hunt, 217[/ref]. Between February 1831 – when he took his seat – and August 1832, he made over 1,000 parliamentary speeches; he continued to call for justice for Peterloo; presented countless petitions on behalf of impoverished workers; and introduced a bill supporting women’s suffrage[ref] Margaret Escott, ‘HUNT, Henry (1773-1835), of Middleton Cottage, Andover, Hants and 36 Stamford Street, Mdx.’ in The History of Parliament: The House of Commons 1820-1832, ed. D. R. Fisher (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009)[/ref].

However, Hunt alienated many of his supporters with his criticism of the proposed Reform Bill. Hunt noted that the proposed changes failed to enfranchise or benefit the working classes. He told the crowds at Leeds: ‘I am determined the Working Classes shall have the reform they want, and by the living G-d [God] I’ll resign my trust before I desert my Constituents or the Working Classes of England’[ref]Henry Hunt, No. 6: An Address from Henry Hunt, Esq. M.P. to the Radical Reformers of England, Ireland, & Scotland… (London, 1831), 44[/ref].

Yet, his scepticism was not shared by other politicians or much of the public. His objections led to him being labelled a Tory conspirator. One working-class newspaper claimed the real reason for Hunt’s opposition was ‘that this is not his Reform. It is not Mr. Hunt’s Bill. The people do not talk about the great reformer, Mr. Hunt, and he foresees the end of his influence[ref] ‘Henry Hunt,’ Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 3 July 1831[/ref].

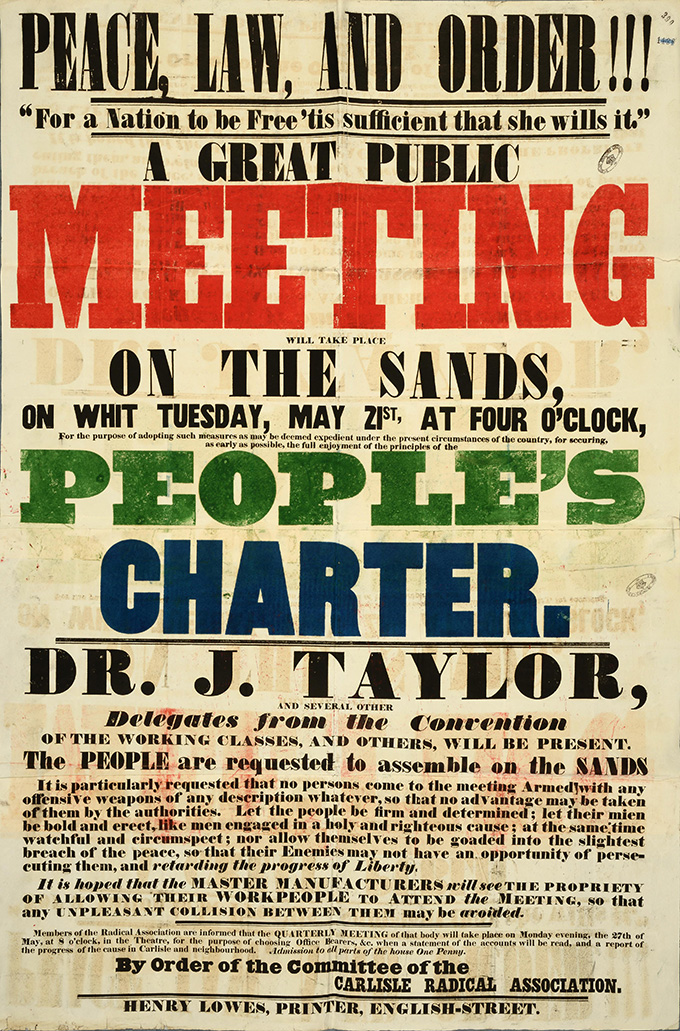

A poster advertising a Chartist public meeting chaired by Dr J Taylor in Carlisle 1839. Many Chartists continued Hunt’s insistence on non-violent protest meetings and his calls for universal suffrage and annual parliaments. Catalogue reference HO 40/41/1

Hunt’s campaign against the Reform Bill resulted in him losing his seat in the first general election that followed the passing of the Act in 1832. Following his ousting from parliament, he attempted to continue his work in radical politics, but was limited by his declining health. He died soon after suffering a stroke on 13 February 1835.

Despite declaring that he would ‘die the victim of patriotism,’ in the years following his death, Hunt’s reputation was restored. He was held up as the saviour of working-class politics and inspired the Chartists, who called for universal suffrage and parliamentary reform.

Michaela Jones is a PhD researcher at Royal Holloway University and was a volunteer researcher on the Archives Alive: Peterloo project.

A great man, we owe so much, long live his deeds and memory !

Tom Webzell

Very helpful details of the trajectory of Hunt’s influence. I am writing a novel of the following generation about the orphan and workhouse. I’m in the U.S.

No reply necessary. Just wanted to thank you.