On 4 December 1961, the contraceptive pill was introduced on the NHS in the UK for the first time. Although it was a relatively low key moment in parliament, it was to have a huge impact on millions of women, influencing everything from their sexual lives and family units to their economic freedoms. Sixty years on, the pill still often tops lists of things that have had the biggest influence on women’s lives, and as of 2019, 151 million women were believed to be taking the pill worldwide[ref]Contraceptive Use by Method 2019 – the United Nations.[/ref].

Despite the significance of this moment, the contraceptive pill was originally only introduced for a very limited number of women at a doctor’s discretion and, contrary to popular belief, many forms of contraceptives were already widely available. What is significant here was the more explicit state support, when just decades earlier discussions in government were rife around the policing of advertising and promotion of contraceptives.

In this blog I am going to focus on the contraceptives that were available, and the government response, rather than the wider birth control movement and family planning centres.

Syringes, enemas, whirling sprays and douches

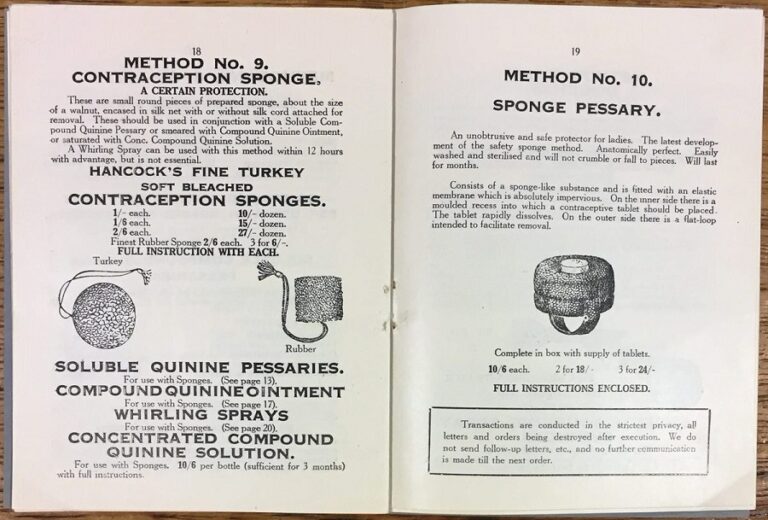

To really understand the impact of the pill it is necessary to look at life prior to its existence. Before the advent of the pill many, varied contraceptive options already existed: from French letters or rubber sheaths (condoms, used by men), to pessaries, contraceptive sponges and douches (used by women). The withdrawal method continued to be a popular preventative too. Birth control was the common term for contraceptives in the 20th century, however other, less explicit phrases were often used in advertising, such as ‘surgical appliances’, ‘female remedies’ and, for sellers of items, ‘herbalists’. Suppliers would target individuals through trade catalogues, which would be posted through letter boxes, often to unsuspecting individuals[ref]Documents reveal that individuals were often targeted if they had just announced a marriage or a birth in the local press. The National Archives, HO 45/10932/157111.[/ref]. Such services also provided a more discreet and respectable way of procuring contraceptives, for all classes of people[ref]Claire L Jones, ‘Under the Covers? Commerce, Contraceptives and Consumers in England and Wales, 1880–1960’, Social History of Medicine, Volume 29, Issue 4, November 2016, p.746.[/ref].

Government records show the policing and attempted control of these advertisements and catalogues, leaving us with a wealth of interesting items seized by the authorities which sometimes end up enclosed in our records. To locate 19th and early 20th century contraceptives in our collections, phrases such as ‘obscene’, ‘abortifacients’ and ‘indecent publications’ need to be used as search terms, reflecting the language of the time. The use of language such as abortifacients, relating to preventative contraceptives, is reflective of contemporary attitudes. Preventing conception was often deemed more controversial than abortions themselves, as this signalled an intention to have sex for the sake of sex itself, not procreation.

The fact that such publications were reported to the police or Home Office, at least by some individuals and societies, tells us something about the attitudes towards contraceptives at the time, and how divisive they could be. However, the nature of government archives also means we predominantly record the controversial cases; for many people, contraceptives were part of their lived reality. As this quote from a woman married in the 1940s women shows:

‘it was years before the pill, and it was just usual for the man to take precautions … You see things are very different in the ’40s … Everything was left to the men.’

Hilda, quoted in Simon Szreter, Kate Fisher, ‘Sex Before the Sexual Revolution: Intimate Life in England 1918-1963’. Cambridge, 2010. P.253.

Kate Fisher has argued that birth control in this period was more of a male domain, with women preferring that men primarily looked after contraceptives.

Automated rubber slot machines

By the 1920s, single-use rubber condoms had been developed, although the use of various other birth control methods also continued. In the 1920s and 1930s automated slot machines selling rubber sheaths started to pop up around the country. Much like leaflets put through letter boxes, they removed the embarrassment of face-to- face interaction.

Though seemingly not many in number, they attracted considerable attention. Many complaints were sent to the Home Office from organisations as varied as the Mothers Union to the Methodist church. One individual wrote in to complain of the ‘harmful moral effect’ of this ‘public evil’, while a school teacher claimed to wholeheartedly agree with contraceptives but was concerned about the impact of such automated condom machines on teenagers. Images in our collections show chemists that had prompted complaints due to the contraceptive machines affixed to their shop fronts, such as in Birmingham and Leeds in the 1930s[ref]Publications (including indecent publications): Literature advertising birth control methods, 1934-1937. HO 45/17040, The National Archives.[/ref].

Throughout the 20th century, birth rates had steadily declined, and the first half of 20th century had seen an increased use of birth control methods. Women were starting to see conception as more of a joint responsibility. Contraceptives were increasingly visible in society; present on the street, in these slot machines and shop displays; seen in national debates taking place in the press about family planning clinics; and, very literally, in people’s homes.

So, how did the contraceptive pill develop from this context? The second part of this blog will explore just that.

It was not until 1972 that the contraceptive pill was free on the NHS. Objections to contraceptives, specially on the contraceptive pill, were based on religious grounds of stopping creation. Unfortunately some women tried their own form of contraception in which at least one woman died through her own experiments.