Today (and tomorrow morning) mark the 198th anniversary of the Pentrich Rising in 1817. Sometimes referred to as ‘England’s last revolution’, the rising took place on the evening of 9 June 1817 and the morning of 10 June. Around 50 radicals assembled at about 10pm on 9 June near the village of Pentrich, Derbyshire with a small number of weapons. Those involved had been assured that there was a large force rising elsewhere, and that the revolutionaries would converge on London.

They tried to take an iron works, but were held off by a few constables. Eventually the company was met by about 20 dragoons in Nottinghamshire and dispersed. Within three weeks a total of around 85 were arrested.

24 rebels were tried at a special court in Derby, with those convicted of involvement often sentenced to death. However, most of the sentences were subsequently commuted; 14 were transported, others were imprisoned. However there was no such reprieve for Jeremiah Brandreth, William Turner and Isaac Ludlam; labelled as the ring leaders, they became the last men in England to be sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered.

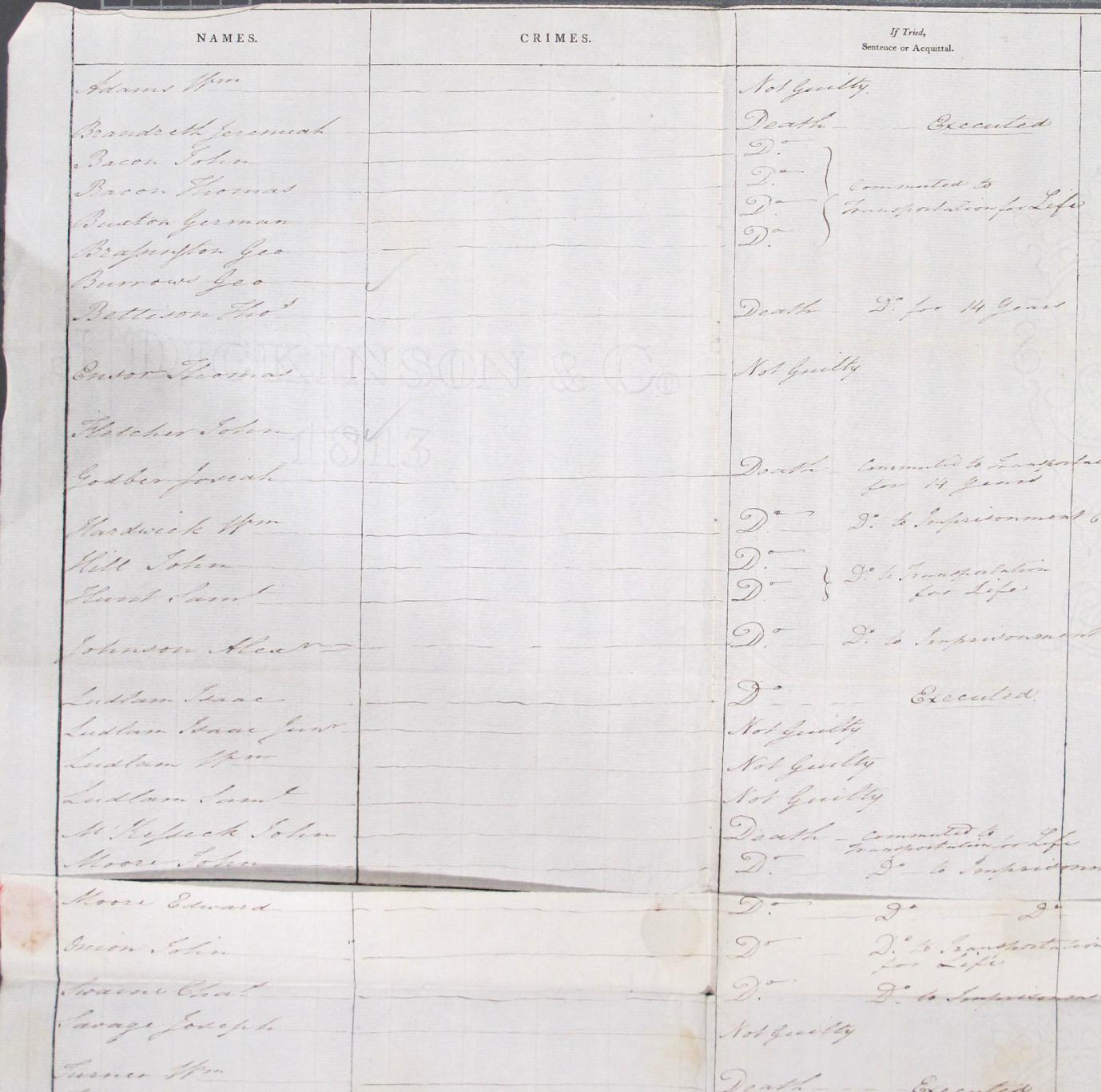

Home Office Criminal Register, 1817, showing the men tried for involvement in the Pentrich rising (catalogue reference: HO 27/13, folio 156a)

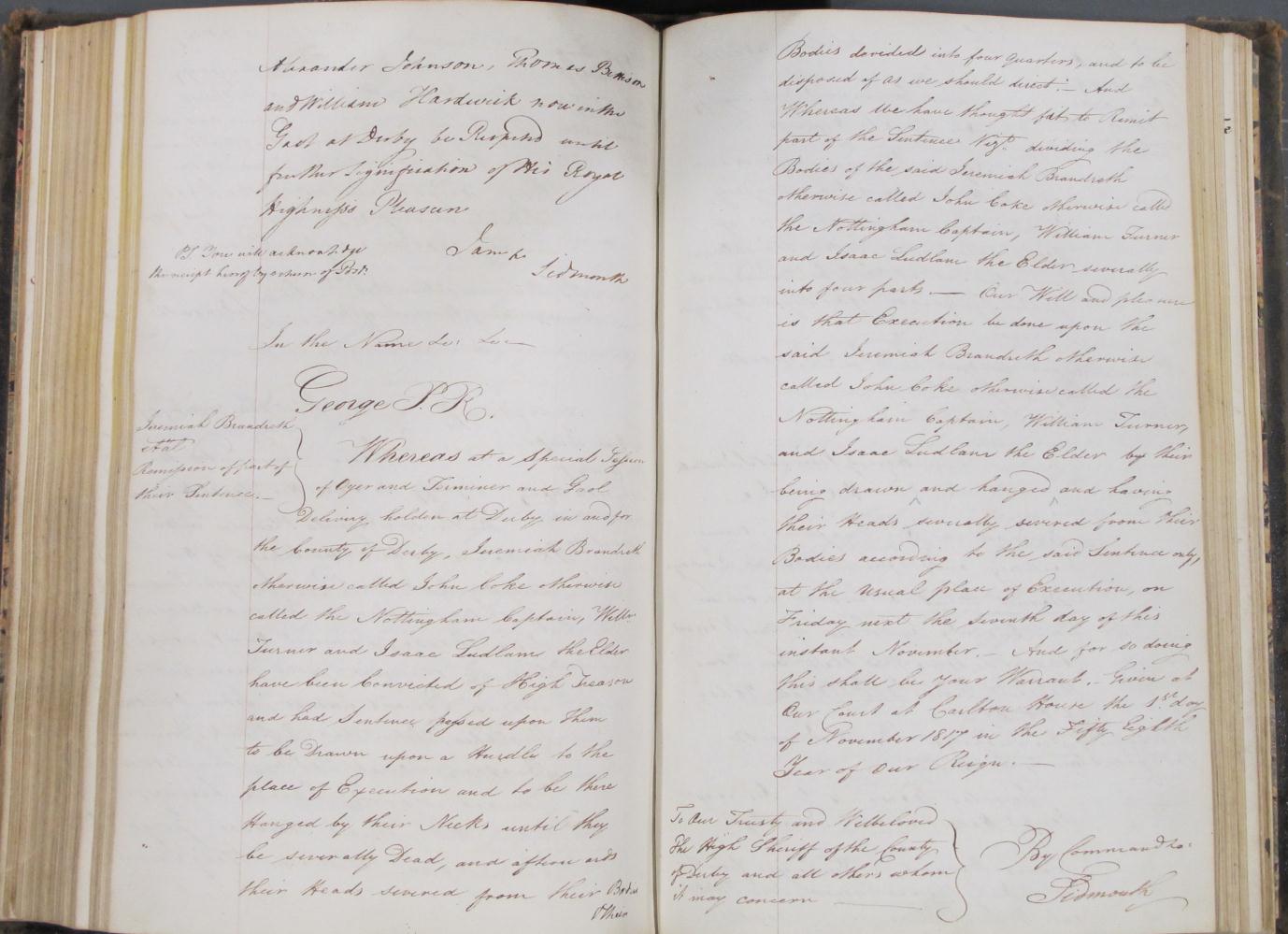

Warrant for Ludlam, Turner and Brandreth’s execution, 1 November 1817 (catalogue reference: HO 79/10)

The Pentrich Rising was clearly doomed from its beginning, with no other force to support it, but the rebels may have well believed the promises of a wider revolutionary movement, as in the spring of 1817 many radicals believed open rebellion was on the cards, as did the government.

The government had good reason to fear general insurrection, England’s economy was in a dire state; the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 had removed the demand of the war machine from the economy, the Corn Laws of 1815 had massively increased the price of bread.

These economic woes hit the poor of society the hardest, and had led to a clamour for something to change.

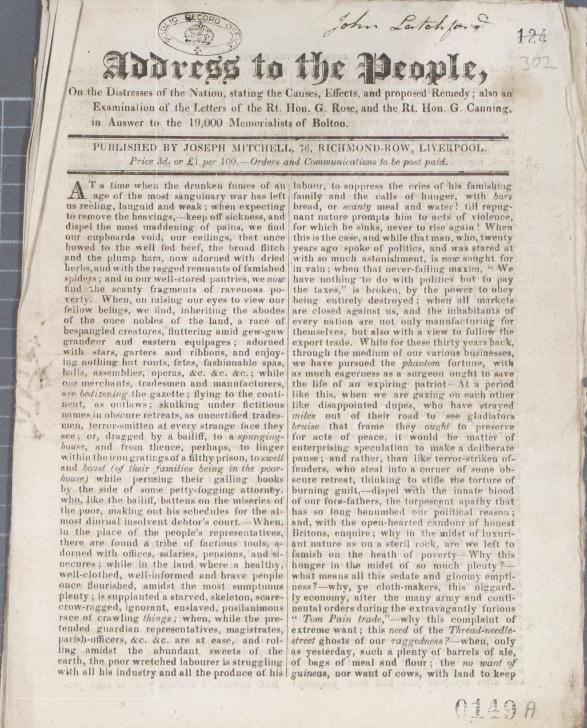

A pamphlet from the time found in the Home Office collections sums up the common feelings of radicals of the time in an eloquent manner, the writer remarks that:

‘we find our cupboards void, our ceilings, that once bowed with well fed beef…now adorned with dried herbs, and with the ragged remnants of famished spiders…The poor journeymen manufacturers, &c. are obliged to work late and early, to get money to pay enormous prices for food, to cruel adulterators of our bread, who are at this melancholy moment poisoning us with their villainy, under the pretence of enabling farmers to pay their enormous rents, and of course, keep up the splendour of the landholder’

The writer proceeds to recommend parliamentary reform, the extension of the voting franchise to working men, as the solution to these woes – so that the corrupt government run by landholders can be replaced. Debating societies discussing these topics flourished in this period. But the government, fearful of the consequences of this national discussion, sought to repress them, even going as far as suspending habeas corpus (trial by jury) to try and supress dissent. Radicalism was pushed underground.

This fear on the government’s part has left us with a rich documentary record of materials relating to early 19th century radicalism in Home Office series such as HO 40 Disturbances Correspondence, the catalogue descriptions of which (along with those of other series) have recently been enhanced as part of a British Academy funded project.

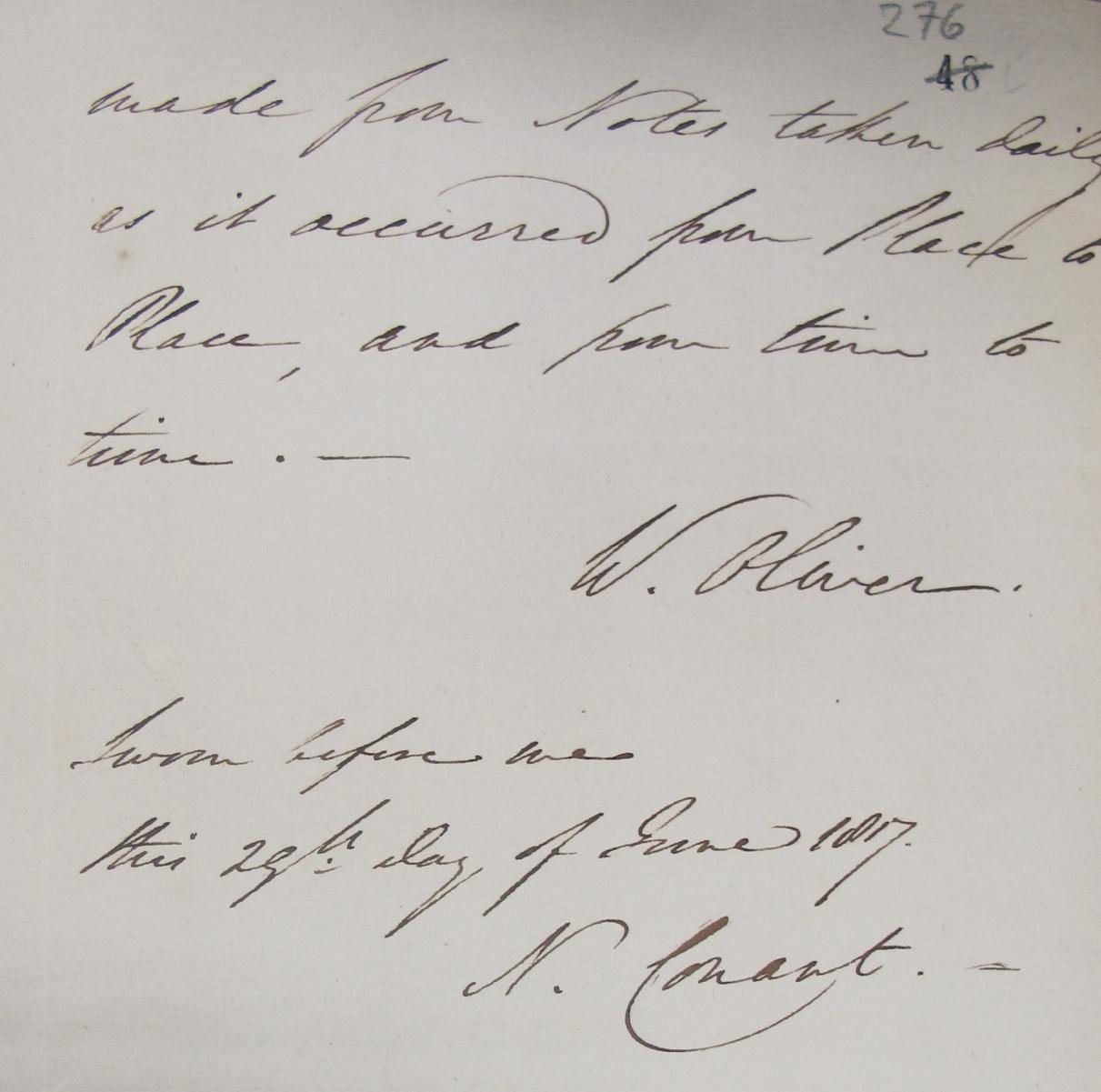

The Home Office established a network of spies and informers who successfully penetrated many radical circles and these give us first hand accounts of the mood of the country – most famous of these was William Oliver, or Oliver the Spy who became infamous as England’s firs agent provocateur, being accused of inciting the rebels to their damned action.

Oliver’s brief but successful career as a Home Office agent is well documented, especially in his accounts of his travels round the country in HO 40/9/2.

He offered his services to the Home Office in March 1817, shortly after befriending famous radical Joseph Mitchell, who was arrested in May 1817. In April, May and early June Oliver travelled round the midlands and the north, posing as a London radical offering support to planned insurrection. Many consider Oliver to be the real architect of Pentrich, encouraging the radicals to doomed action with overstated claims of their support elsewhere.

Along with intelligence received by the Home Office about the run up to the rising and many other details of other radical activity, HO 40 also contains the first reports of the rising sent to London, as well as an account of its aftermath. However, perhaps its greatest strengths are its collection of depositions taken from captured radicals, which give us an insight into how ordinary respectable men became involved in revolutionary action.

HO 40/9/5 contains one such document, that of John Cope, who was involved in the rising, but claims to have fled it whilst it wound its way through Derbyshire.

Cope originally joined a debating society in favour of parliamentary reform. He became involved in signing petitions in its favour, but also met radicals who promised ‘there would soon be a general insurrection’.

On 9 June, he became part of the rising when it came to his home in Ripley at about 3am, when ‘the mob, armed with guns, pikes and a many swords came’.

Cope says he fled the mob during its march, but that before that it was promised that in Nottingham ‘all public property would be seized, the national debt extinguished, and no taxes’. Sounds wonderful, but for the appearance of 20 dragoons.

26 year old George Weightman was one of the rebels transported to Australia for their part in the uprising. Thanks to records in HO 17 (criminal petitions) we can trace what happened to Weightman and his co-accused after sentencing. This may not be something we are familiar with today, but at this time it was possible, even common, to petition for mercy on behalf of a convict – to ask for either a full pardon or a reduced sentence (a conditional pardon). These petitions form part of the Home Office collection in record series HO 17 (1819-1839) and HO 18 (1839-1858). The petitions vary considerably in size, detail and style: there may be a single letter from family and friends, or a large bundle of letters and papers. Petitioners were generally seeking mercy, not justice, so they set out mitigating circumstances to explain a criminal’s conduct or to elicit sympathy. Such details can provide much needed contextual information about a crime and about an individual’s life, adding colour to the often dry, official information recorded in trial papers.

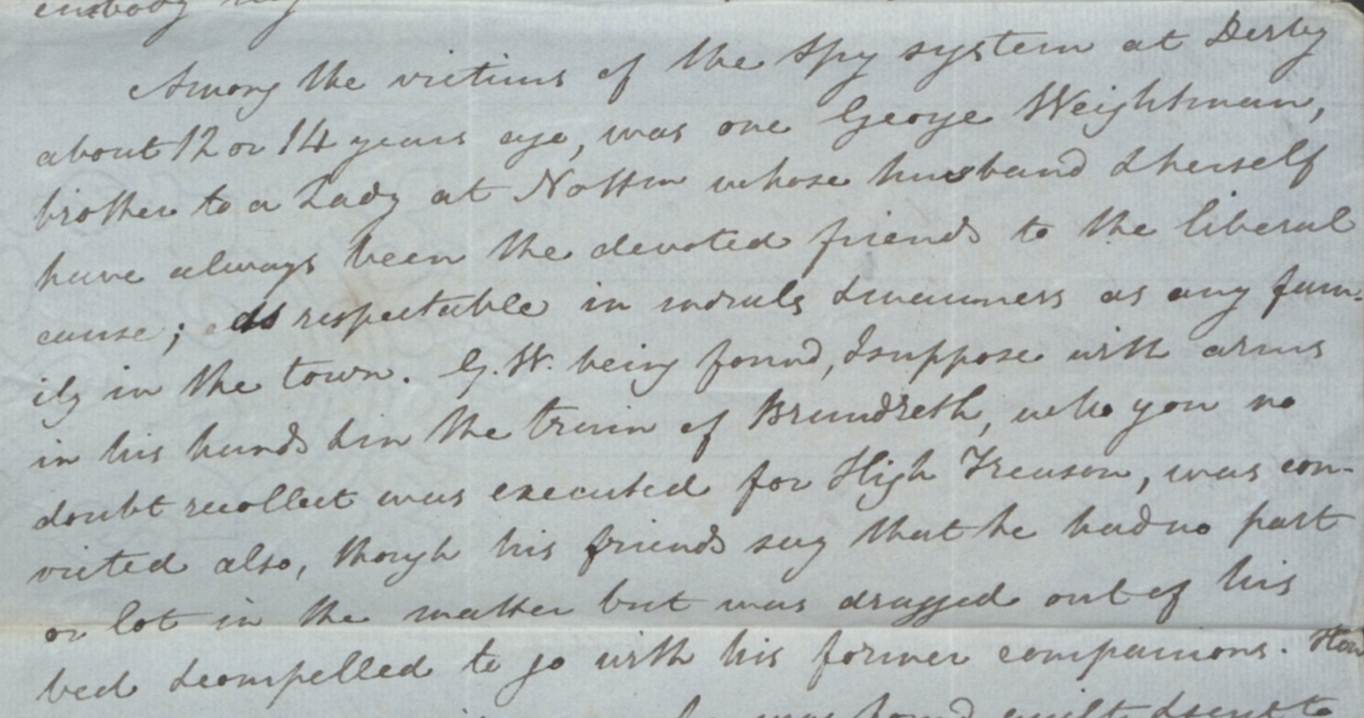

In 1831 Robert Goodacre, an acquaintance of Weightman’s sister, wrote to the Attorney General seeking a pardon so that George might leave New South Wales to join his family in America. In his petition Goodacre stresses Weightman’s naivety and limited culpability. Perhaps rather disingenuously he writes: ‘being found, I suppose, with arms in his hands and in the train of Brandreth’, he was convicted of treason, but his friends state that ‘he had no part or lot in the matter but was dragged out of his bed and compelled to go with his former companions’.

Goodacre also stresses Weightman’s respectability. He describes Weightman’s sister and her husband as very prosperous and ‘as respectable in morals and manners as any family’. Goodacre also highlights his own respectability: he gives astronomical lectures, is an elector in Nottingham, and one of his friends went to school with the Attorney General. All of these nuggets of information are designed to demonstrate that Weightman is deserving of mercy, that his offence was a one off and that if pardoned he will have a network of respectable connections to keep him on the straight and narrow.

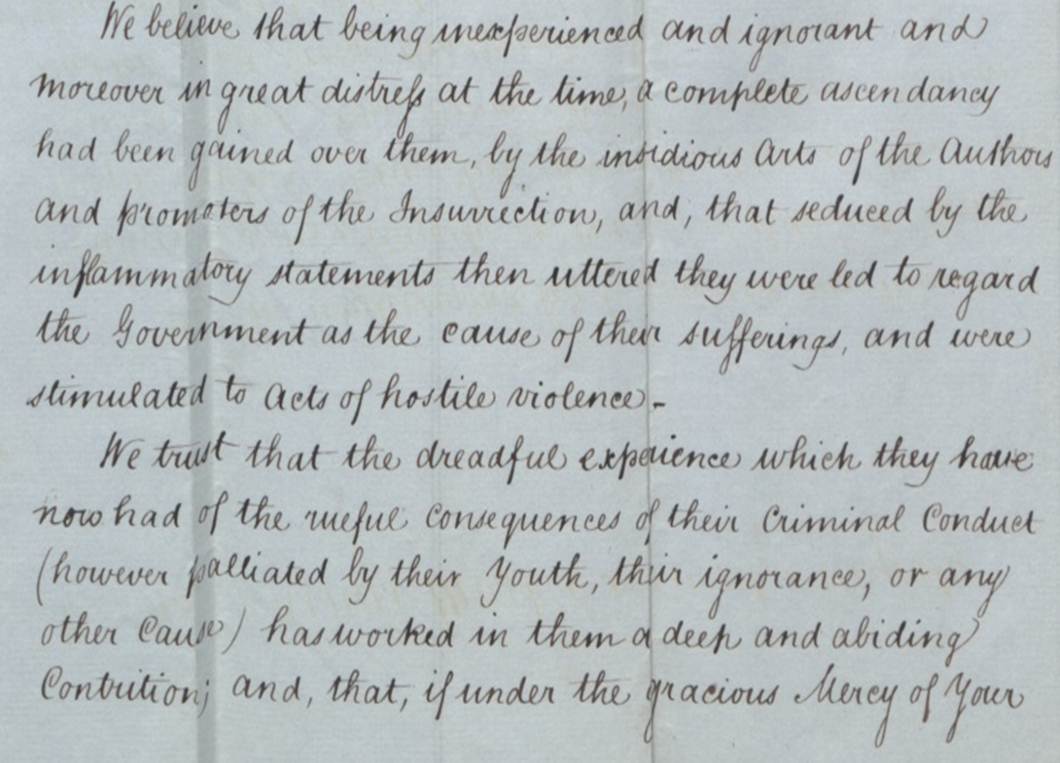

A scribbled ‘nil’ from a Home Office clerk indicates that Goodacre’s petition was unsuccessful. However, this is not the end of the story. On 2 August 1834 Weightman is listed with his co-accused in a petition from some Derbyshire magistrates and MPs. The petition picks up some of the themes mentioned above – stressing the convicts’ youth and naivety, their poverty, and their reformed characters:

This time it worked. 17 years after they were convicted, the Pentrich rebels received a full pardon and were free to return home.

These petitions can be a fascinating way to trace a convict’s story, potentially providing background information about their life and family, as well as clues as to what happened next. As I mentioned in a previous blog, I manage a team of volunteers who are working to make these records name and keyword searchable so that researchers can find cases like Weightman’s much more easily. Researching this blog reinforced how useful this work is: a simple catalogue search for ‘weightman AND spy’ located the 1831 petition in seconds, but it was only having speculatively trawled through three years’ worth of registers to criminal petitions in record series HO 19 that I happened to find the second petition in an as yet uncatalogued box.

Thanks to the cataloguing of HO 17, HO 40, and the other records selected for inclusion in the Home Office Disturbance Papers project, it will be much easier for researchers to piece together the Home Office archive to reveal a more complete picture of this fascinating period of our history.

Hiya, very interesting, we are currently (in the Pentrich/South Wingfield area gearing up to the bicentenary and a massive commemoration including all the local villages that took part in this and Australia and huddersfield where they also rose, (some Huddersfield men were sentenced after the pent rich men to be hung drawn and quartered as we have just found out?) could we gain some contact with you to assist with what we are doing?

We have an official website under construction, we are on Facebook http://www.facebook.com/pentrichrevolution and I personally am researching the revolutionaries http://www.spanglefish.com/pentrichrevolution please get in touch and I can send more details, would love access to some of the documents in this article!, thank you. Sylvia Mason

Hi

I have read several of your posts on Curious Fox and elsewhere.

I do not know whether you are still looking for information on John McKesswick (John McKissock) of the Pentrich Rebellion group but my current research has provided me the following;

John Mc Kissock died 1853 NSW Australia.

I believe his son William went by the name Bestwick or Beswick in the 1851, 1861 & 1881 census as this relates to the 1891 entry of William McKissock in Hucknall Torkard Nottinghamshire – see names of other occupants.

I am trying to find a John McKissock relationship with any of the other rebellion participants.

rgds

Terry Blaker

[…] We are now two years away from the bicentenary of the Pentrich Revolution. Want to know more? Then follow this link to the National Archives’ blog […]

Thank you for your comment Sylvia, and the best of luck with the events you are putting on to commemorate the bicentenary of the Pentrich rebellion.

You can use Discovery, our catalogue to find out how to access the records we mention in the blog, many of which are available online, either from our website or via findmypast.co.uk. If you enter the full reference as a search term, the document description page will tell you how to access that particular item.

For anyone interested in researching Home Office correspondence or records relating to convicts, we have some very helpful guidance on our website which explains how to search for these records. You can access these guides from the ‘Records’ part of our website (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/).

The following guides would be particularly relevant:

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/research-guides/home-office-1839-1959.htm

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/looking-for-person/criminal-trial-or-conviction.htm

what happened to oliver the spy ?

Thanks for your comment F Webster. Oliver’s fate is not something Briony and I have done a huge amount of research into ourselves. However, according to A F Freemantle’s 1932 article ‘The Truth about Oliver the Spy’ (English Historical Review, Vol 47, No 188) Oliver was exposed by members of the press as being a government informant. His life was viewed to be in danger, so he was accordingly given passage to the cape in 1817.

The image above which you describe as Oliver’s signature is in fact a deposition from Oliver taken by the Bow Street Magistrate, Nathaniel Conant, and is in his handwriting, rather than Oliver. Extensive examples of Oliver’s handwriting can be found in his reports to the Under-Secretary of State at the Home Office, John Beckett, in HO 40/10, although he signs his name WJ Richards (his real name).

[…] inn, calling for a march on Nottingham, insisting they would be paid and fed. All the while Oliver kept the authorities informed. Ms Mason said: "The government as good as organised it – they named the day in documents and […]

Why was The Pentrich Revolution so named? What is the significances of Pentrich to the Revolution? Also did any women join in with the march and/or get arrested?