On 19 June 1829, Sir Robert Peel’s Act for Improving the Police in and near the Metropolis received royal assent. Peel argued that there was a real need for the establishment of a new police force stating that:

It is the duty of Parliament to afford the inhabitants of the Metropolis and its vicinity, the full and complete protection of the law and to take prompt and decisive measures to check the increase of crime, which is now proceeding at a frighteningly rapid pace.[ref] David Ascoli, ‘The Queen’s Peace: The Origins and Development of the Metropolitan Police 1829–1979’ (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1979), p. 76.[/ref]

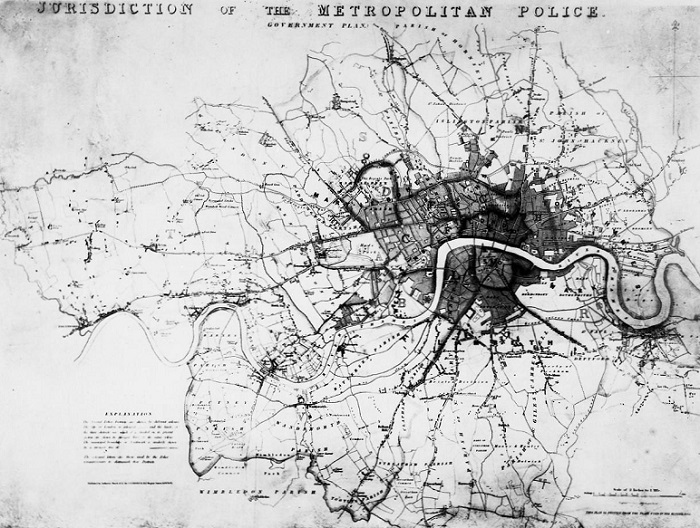

Map of Jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Police, 1837. Catalogue reference: MEPO 13/326

Between 1823 and 1830, Peel introduced a series of reforms which radically changed law and order in Britain. Prior to these reforms, conditions in prisons had been horrific – they were overcrowded, filthy and disease-ridden. Child offenders and hardened criminals were housed together; jailers were prone to violence and were unpaid, meaning that they had to extort money from prisoners in order to make a living. On top of this, Britain had no police force, relying instead on the antiquated system of ‘hue and cry’, the Bow Street Runners and night watchmen.[ref] Norman Lowe, ‘Mastering Modern British History’, fifth edition. (London: Palgrave, 2017), p. 22.[/ref]

Contemporary accounts suggest that London was a ‘thieves’ kitchen’, with organised gangs ruling the streets. This popular perception of crime in London can be summarised in the poem ‘Ways of the Town’, which reminds its readers to:

‘Prepare for death if here at night you roam,

and sign your will before you sup from home.’[ref] Gary Mason, ‘The Official History of the Metropolitan Police’ (London: Carlton, 2004), p. 9[/ref]

Peel was a strong advocate of crime prevention rather than of harsher punishments for those found guilty. During his time in office he made three key reforms in an attempt to prevent crime. The first of these was the penal code reform which abolished the death penalty for over 180 crimes, along with the practice of burying suicides at crossroads with a stake through the heart. The government also stopped using spies to report on ‘would-be’ troublemakers. The Jails Act (1823) enabled magistrates to inspect prisons up to three times each quarter, and for jailers to be paid for the first time, and allowed all prisoners to have visits from doctors and chaplains.

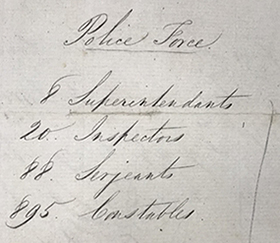

Detail of the strength of the Metropolitan Police force, 1829. Catalogue reference: MEPO 2/10768

Peel was also convinced that having an effective force to track down and deter criminals would make the law more effective and the prison system more manageable.[ref] Lowe, ‘Mastering Modern British History’, p. 22[/ref] Between 1811 and 1827, it had been estimated that crime had risen in London and Middlesex by 36%.[ref] ‘Report from the Select Committee on the Police of the Metropolis’, House of Commons Papers, 1828, no. 533, vol. 6, p. 7[/ref]

On 29 September 1829, in a direct attempt to reverse this trend, Peel established the Metropolitan Police. At the time of its establishment, the Metropolitan Police had eight superintendents, 20 inspectors, 88 serjeants and 895 constables.[ref] Catalogue reference: MEPO 2/10768[/ref]

The recruitment criteria for the new Metropolitan Police Force was that men had to be under the age of 35, in good health, strong and at least 5ft 7in (1.7 m) tall.[ref] Mason, p. 12[/ref] Having entered the force, recruits were not allowed to visit public houses, talk to prostitutes, associate with known criminals, or cultivate them as informants. These decisions were taken largely as a result of the public outcry that former voluntary upholders of the law had been in the pay of criminal gangs.[ref] Ibid.[/ref] A strict stance was taken on officers’ behaviour and within two years of the Metropolitan Police being established, more than half of its officers had been dismissed and replaced for alcohol-related offences.[ref] Ibid., p. 13[/ref]

At the time of its establishment the Metropolitan Police was tasked with controlling the crime in its vicinity, rather than shutting down or driving out the various establishments that attracted the criminals. [ref] Ibid., p. 14[/ref] The main way that the new officers ‘policed’ their areas was on foot, patrolling interlocking ‘beats’ and reporting to their sergeants at pre-arranged points throughout their shifts.

Peel’s police force was a clear success and recorded crimes certainly appeared to drop significantly after 1830. By the turn of the next century, there were fewer reported crimes than there had been seventy years earlier, despite a population growth of five million in the city.[ref] Ibid., p. 13[/ref] There were even growing complaints from provincial authorities that Peel’s ‘raw lobsters’ had been so successful in the metropolis, that they had driven the criminals out into the midlands and the north of the country.[ref] Ascoli, p. 97[/ref]

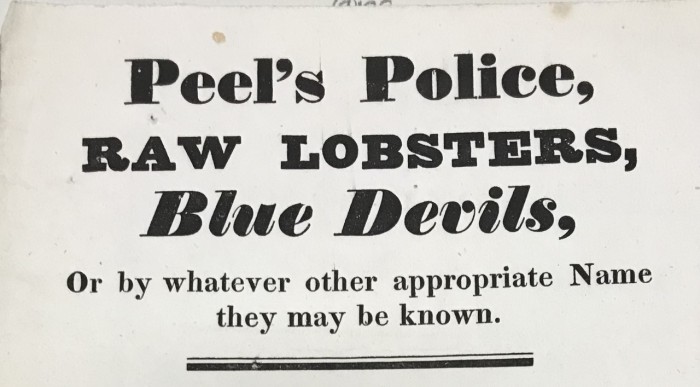

Anti-police handbill, 1830. Catalogue reference: HO 44/21, f. 326

Soon after the Met’s establishment, there were criticisms levelled at both its officers and Peel. Quickly after their appearance on the streets, the officers in their blue uniforms earned the nicknames ‘bobbies’ and ‘peelers’ – a clear reference to the fact that they were directly responsible to the Home Office and therefore the Home Secretary. Some people even felt that Peel was developing his own personal army.[ref] Mason, p. 12[/ref] There was also growing concern that the truncheons carried by the police posed a threat to the public. In a handbill entitled ‘Peel’s Police, Raw Lobsters, Blue Devils’ details are given of how the public will be distributing ‘staves of superior effect’, which could be used if the police begin to attack people.

Despite the criticisms levelled at Peel’s new police force, it was hoped that the Metropolitan force would be used as a model for reformed policing across the country. In 1835 the Municipal Corporations Act required that all new local councils appoint paid police constables. This brought professional policing to 178 towns in the United Kingdom.

In 1839, the Rural Constabulary Act allowed entire counties to set up their own police forces if they wanted to and Wiltshire became the first county to do this. Although legislation did not insist that local authorities establish their own police force, by 1851 there were more than 13,000 police officers across Britain, showing the huge success Peel’s ‘raw lobsters’ and ‘blue devils’ had been.[ref] UK Parliament accessed 28/03/2019[/ref]

A good read but you left me baffled as to what the nickname ‘raw lobsters’ was supposed to mean. Googling turned up a BL article (shame on you TNA!) with the answer that “Raw lobsters are blue and only turn red when boiled: the suggestion being that the police in their blue coats were only ‘hot water’ away from becoming the red-coated army.”

Great article, thank you. Linked to here by the Reform & Radicalism course on FutureLearn (which is great course, by the way).

“The recruitment criteria for the new Metropolitan Police Force was that men had to be under the age of 35”

So it was okay to be nine years old? Surely there was a minimum age?

It says “MEN had to be under the age of 35”. A nine year old boy is not a man, so he wouldn’t be admitted.