In the Collection Care Department we are responsible for preserving the documents stored at The National Archives and ensuring that the public can access them. Decades ago, in an effort to meet these goals, conservators at The National Archives laminated many commonly accessed documents in the collection using semi-transparent tissues.

These ‘area bonded fibre laminates (ABF)’, are covered on one side with a thin layer of adhesive (usually a synthetic acrylic polymer). During lamination, a document was sandwiched between two ABF tissues and pressed using a heat press at approximately 85°C for one minute. In the 1970s and 1980s, this process was considered state-of-the-art in ensuring document preservation.

Promotional materials and samples sent to The National Archives from manufacturers of lamination presses and laminate tissues.

Cartoon showing lamination materials and the process.

Although the ABF laminate tissues and synthetic adhesives used on many of our documents are in relatively good condition, times have changed and lamination is now not only considered unnecessary, but in some cases, unsightly.

In addition, the long-term effects of the adhesives have not been fully explored, nor could the consequences of lamination be known or studied for every type of paper and ink in our collection. So earlier this year, conservator, Ilaria Budgen, and I started exploring strategies for safely removing the lamination. We created model samples for testing using de-accessioned documents written on a variety of paper types, with text in iron gall ink, pencil, wax pencil, ball point inks, printer inks, and stamp inks. The models were artificially aged using heat and high relative humidity to accelerate some characteristic deterioration processes.

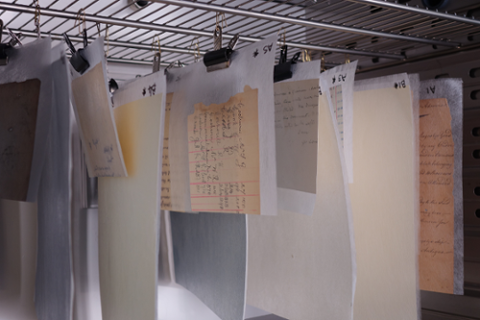

Model laminated samples hanging in our artificial ageing chamber.

Most contemporary conservation treatments should be reversible, or at least ‘re-treatable’. In the brochures for ABF laminate tissues, you can often spot a statement like ‘spirit reversible’, which may lead to a false sense of comfort. But what does ‘spirit reversible’ mean in the context of a document fully encapsulated in laminate? Should we bathe the document in spirits to dissolve away the adhesive? Which type of ‘spirit’? This term is used both for ‘white spirit’ and ‘rectified spirit’ – essentially paint thinner and alcohol, respectively.

Critically, since the documents are already laminated, we cannot check if any of their inks are sensitive to either type of spirit. Without this knowledge, we risk losing the writing by attempting to reverse the lamination with a ‘spirit’ wash.

We first tried reversing the lamination using heat. Since the ABF tissues were applied using a heat press to activate the adhesive, we thought we might be able to use heat to reactivate it and peel off the laminate.

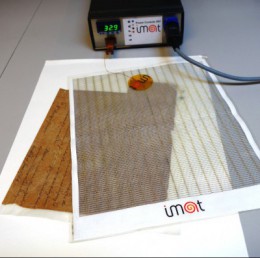

To achieve this in controlled way we used a prototype iMAT on loan to us from the Munch Museum in Oslo, Norway. The iMAT is a transparent mat containing carbon nanotubes and silver nanoparticles, which can heat up in a precise and controlled matter at a rate of 0.1°C.

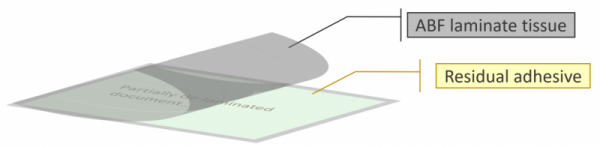

We attempted to remove the laminate from our model samples after they had been pressed under the heated iMAT at different temperatures and for different time periods. Unfortunately, we discovered that the adhesive sticks more strongly to the paper than to the semi-transparent ABF tissue. Once reheated, the ABF tissue easily peels off, leaving a layer of adhesive on the paper beneath!

The iMAT and its controller console on top of a model laminated and artificially aged document.

A magnified image of the ABF laminate tissue fibres – in this case, made of nylon.

A cartoon of our results after trying to remove the lamination with heat alone – the ABF tissue comes off, but the adhesive remains on the document sample.

Over several months of testing, Ilaria developed a method for removing the ABF laminate and the majority of the accompanying adhesive using acetone vapour delivered through a microporous tissue.

This technique greatly reduces the risk of dissolving away the inks, and we can test in a small area of the document first, to ensure that the inks are not affected.

Now Ilaria and I are working on a series of experiments to measure whether all of the adhesive is being removed by her treatment method. We’ve also started testing whether the lamination has beneficial properties for the documents, like protecting some inks from fading over time. Stay tuned for the results of these studies!

This is a fascinating article. I am interested in your reference solely to use of ABF tissue, since we supplied very large quantities of paper tissue for the same purpose. Our L2 was 100% abaca fibre. However the adhesives were usednot just by conservators but also by intermediaries like Ademco. My recollection is that Ademco used Paraloid B-72 (also known as Acryloid) or a similar adhesive for the tissue supplied for conservation. Paraloid B-72 is a copolymer of ethyl methacrylate and methyl acrylate.

The concern at the time was blocking (i.e. adjacent sheets of laminated tissue or a whole book adhereing together in solid block). There was a lot of testing for this then whilst conservators seemed to accept the claim for reversibility long term which your research seems to disprove.

It is worth bearing in mind that Ademco used other tissues and other adhesives for their main line of business supplying other users of drymounting presses such as photographers. I wonder what the legacy of these is.

At one time we also supplied very large quantities of L2 tissue and before that Green’s 105 Lens Tissue to the National Archives in New Delhi. They were continually inviting us to quote for celluslose acetate sheets for use in their presses. As I was aware of a lot of concern about cellulose acetate, I declined to supply it.

I once had the opportunity the visit the National Archives in New Delhi where I was interested to find they were using steam heated (and prossibly steam propelled) presses and I would imagine the temperature may have been higher than 85 C.

My understanding that the Indian National Archives had followed the lead of either the Public Records Office (later TNA) or the British Museum Bindery (later BL) in this, particularly for newspapers. It was, I think, in succession to silking. Silk did seem much more consipicuous than tissue in examples I have seen and the silk also appears to yellow or brown and become brittle more than tissue (or at least our tissues).

Lamination was progressively rivalled by encapsulation. As a paper scientist, I was concerned in that case about sealing the paper and its degradation products into a bulky (and visually unattractive) capsule but there was lots of research showing this was fine. I wonder what current research as been done on paper encapsulated decades ago.

Hi Simon,

Thanks for your thoughtful and insightful comment! Your experience with the Indian National Archives was also really fascinating. I have to say, it’s reassuring to know that as a supplier, you chose not to provide cellulose acetate laminate!

Other types of laminating tissue were indeed used at TNA in the past, including Crompton, Archibond manila fibre tissues, L2 and lens tissues. The backing heat-set adhesives were analysed by researchers in our department about a decade ago and revealed a variety of synthetic polymers, including poly(vinyl acetate), poly(ethylene-vinyl acetate), and acrylic-based adhesives (Paraloid B-72, Texicryl 13-002, Plexitol B500/M630)… the list goes on but I won’t go into the technical details here.

This project started with the hope of removing heat-set laminate from some of the documents within HO 45/24514, which contains Oscar Wilde’s sentencing to hard labour. Analysis showed that the laminate used in this file was a combination of nylon ABF and Archibond adhesive (Paraloid B-72 and Texicryl 13-002). To help with Ilaria’s conservation treatment, we set-up the model samples using this combination and so, our initial testing is limited to the nylon/acrylate lamination type. I would be very interested in expanding the research further, and looking into different combinations of laminate tissues/adhesives.

What we find in general, is that the tissue itself is not all too difficult to remove; it is the adhesive that is the problem (as one might expect, especially having been applied with heat and pressure, and like you said, possibly harsher conditions). In tests carried out at TNA in the past, paper tissues and PVAc-based adhesives were removable or at least ‘swellable’ with water. However, we are trying to find a method which does not require wetting of the document.

As for encapsulation, you are correct – trapping of acidic deterioration byproducts was shown for mylar encapsulated documents by the Library of Congress. I believe this process is now only used for specific types of documents. You may already know these publications but I found the sequence of papers by Down et al. (Evaluation of selected adhesive tapes and heat-set tissues) and the review of cellulose acetate lamination by McGrath et al. (Cellulose Acetate Lamination: A Literature Review and Survey of Paper-Based Collections in the United States) very useful. Nonetheless, there seems to be a relatively limited body of research into this historic common practice, and I think there is space for a lot more work on this difficult problem!