Last time, I blogged about the fate of antiquities and ancient monuments in times of war. You’ll be pleased to know that archaeology was also a concern during the peace-building process.

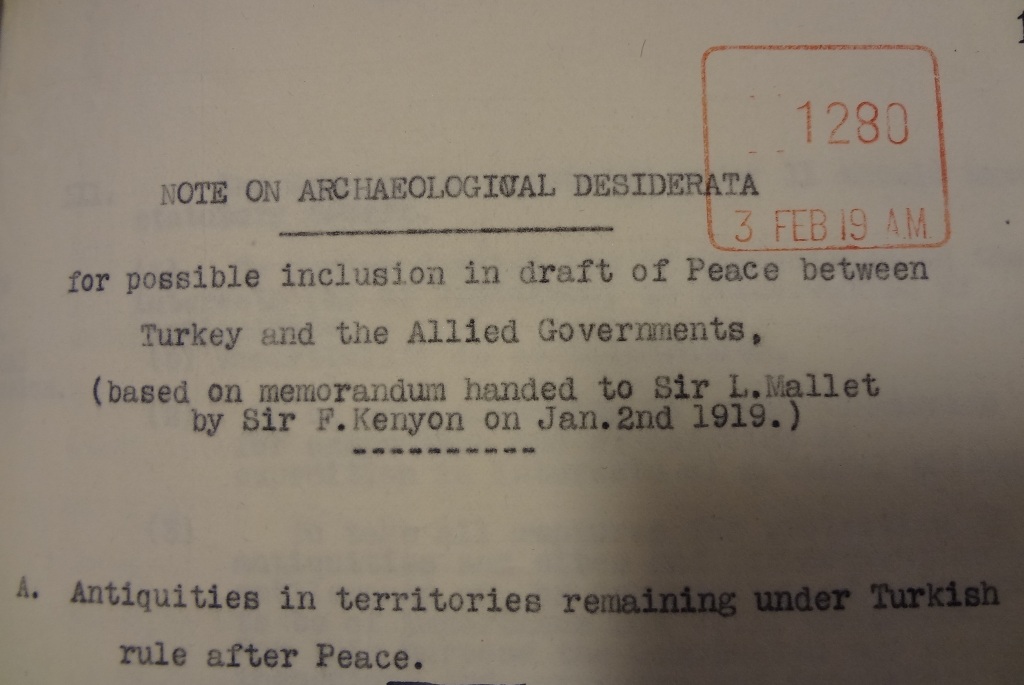

While it was felt that the establishment of an Institute of Biblical Archaeology in Jerusalem ‘hardly concerned the Peace Conference’, which had opened in January 1919 to determine the terms of peace, archaeological matters kept cropping up in Paris, and were mentioned in the Treaty of Versailles as well as in the Treaty of Sèvres. As early as February 1919, a ‘Note on archaeological desiderata’ was presented to the British delegation (FO 608/116).

As it was established that Britain would obtain mandates over Palestine and Mesopotamia, the Delegation, the Foreign Office and the India Office paid special attention to these regions. The necessity of including archaeological clauses in the Treaty of Peace with Turkey was made quite clear. There was, after all, ‘no security that the representatives on the spot of each mandatory power will have any sympathy with antiquarian matters’ (FO 608/240).

There was no shortage of views, and the British Delegation to the Peace Conference was inundated with proposals, some sounder than others – six letters suggested returning the Mosque of Saint Sophia, in Constantinople, to Christendom as it had been built as a Byzantine church; the opinion of the Delegation was very clear: ‘the writers are rather a scratch lot’ (FO 608/116).

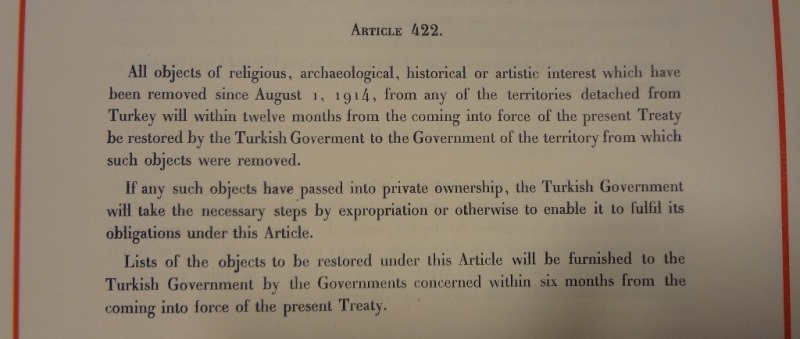

A committee, with one archaeologist for each of the Big Four (Britain, France, Italy, the United States) was formed, and, along with Foreign Officials, started drafting. It was decided that the Turkish government should return the antiquities removed from those provinces which were to be detached from the Turkish Empire during the war, and that local governments should submit lists. Overwhelmed by requests to trace various artefacts in advance, an irritated Delegate to the Peace Conference noted in June 1919: ‘we can hardly follow up and recover each tile!!’ (FO 608/82).

Archaeologists are not immune to greed, however, and John Garstang, who was about to leave for Palestine to head the School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, asked for all the antiquities removed from 1900 to be returned – mostly because he was hoping to open his own museum. As T E Lawrence, noted, this would set a dangerous precedent: ‘if we demand them back, we open the door to demands by other powers on the same principle, for antiquities looted by us or by France and Germany before the war’ (FO 608/82).

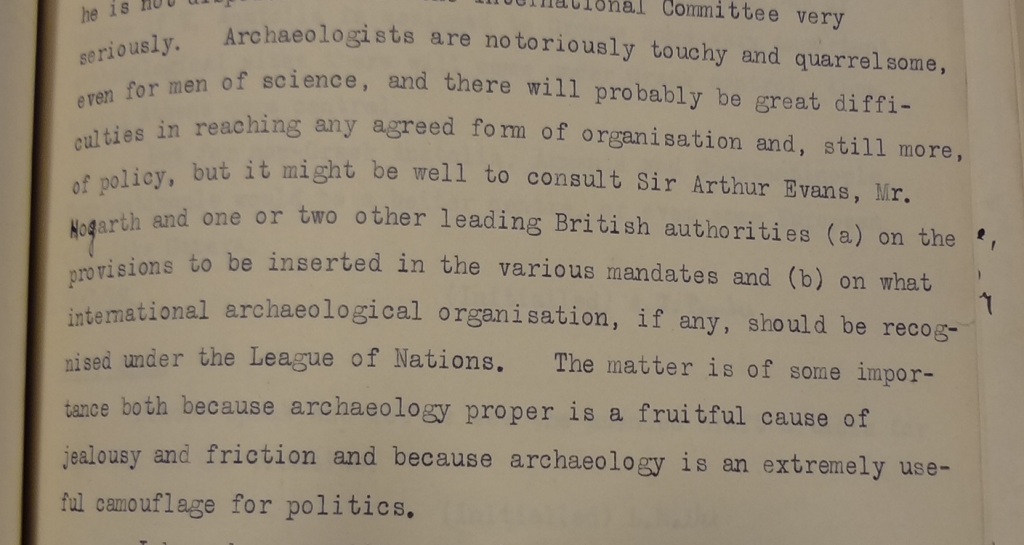

It was, at first, all very international. Hogarth thought it was ‘inconceivable’ that the Germans should be barred from the archaeological committee, the Archaeological Joint Committee of the British Academy suggested an international control over antiquities in countries under Turkish rule, and archaeologists and diplomats of all nationalities agreed that excavations should be allowed to resume as soon as possible – it was almost a League of Nations on a smaller scale (FO 608/82).

However, as the Peace Delegation noted, ‘archaeologists are notoriously touchy and quarrelsome, even for men of science’, and the spectre of old rivalries soon raised its ugly head again (FO 608/116).

Carchemish, for instance, where Leonard Woolley and T E Lawrence had conducted excavations before the war, was placed within the French sphere of influence, in Syria. Sir Frederick Kenyon, the Director of the British Museum, issued in January 1919 a hardly veiled threat against monopolies, clearly directed at the French: ‘it should also be made clear that any nation whose law on antiquities imposes harsh conditions on foreigners or which maintains a selfish monopoly of archaeological privileges in its sphere of control should modify its methods if it desires to enjoy rights of research outside its own provinces.’ (FO 608/82). He was even more transparent a year later: ‘I do not think that any difficulty will arise in Paris, where it is fully realised that French scholars cannot expect to have facilities to work in Palestine or Mesopotamia if they do not grant them in Syria’ (FO 371/4176).

Carchemish, however, was a sensitive topic. The foreign office warned: ‘Jerablus is, of course, a very sore subject with the French, as the pre-war habitat of Colonel Lawrence, whom they will certainly not welcome in a French zone’ (FO 371/4176).

Apart from the usual bickering between the French and the British, Germanophobia was surprisingly vivid in archaeological circles, notably in Egypt, where accusations of espionage soon started flying around.

According to articles 297 and 298 of the Treaty of Versailles, the properties of the German State abroad were to be liquidated. Through the Swedish consul, German Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt wrote to the British government, arguing that the buildings housing the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo were his private property and, as such, should be released, especially as he had diplomatic immunity. This triggered two types of reactions – sometimes coming from the same people. On the one hand, Borchardt was a respected Egyptologist whose manners were sometimes disliked, but whose achievements were generally admired. The dispersion of the library of the institute, which had always been at the disposal of archaeologists of all nationalities, raised serious criticisms. On the other hand, he was a German – therefore an enemy and probably a spy (FO 141/440/1).

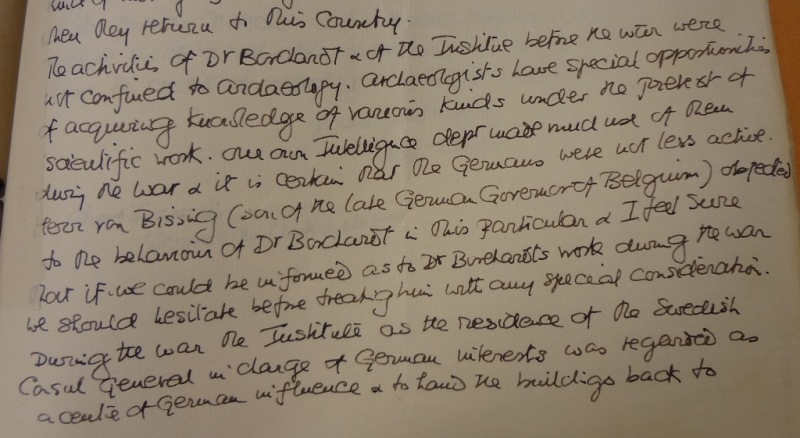

As I have already explained in another blog post, archaeology and espionage often walk hand in hand, but it seems that Borchardt was mostly innocent – even though his deputy, Curt Prüfer, had suspicious political inclinations and was generally believed to be ‘a spy first and a scholar in the second place only’. Cecil Firth, Chief Inspector of the Antiquities Department acknowledged that the Library of the Institute couldn’t be dispersed, and suggested it could be held ‘as hostage for the good behaviour of the German Egyptologists who will, I suppose, one day return to this country.’ He also recalled, however, that ‘archaeologists have special opportunities of acquiring knowledge of various kinds under the pretext of scientific work. Our own intelligence department made much use of them during the war and it is certain that the Germans were not less active’ (FO 141/440/1).

The Director of the Antiquities Department, French Egyptologist Pierre Lacau, who had fought in the trenches and wasn’t one to forget too quickly, wrote quite bluntly that he didn’t understand why anyone would want to return the institute to the Germans, and was particularly hostile to German archaeologists, their presence in Egypt, their approach to Egyptology and their methods in general. He was soon accused by the British to be opposing Borchardt’s return ‘in the interest of the somewhat pretentious French claims to the lion’s share in archaeological research (not only in Egypt but everywhere).’ In the end it was decided, in view of the services rendered by German archaeologists in the past, that the property wouldn’t be liquidated but handed over to the care of the Antiquities Department. The issue of the eventual return of Germans to continue their scientific work was ‘left open for consideration at a later date’ (FO 141/440/1). The German Ambassador in London perceived the decision as ‘a premeditated blow to German scholarship’ (FO 371/6330).

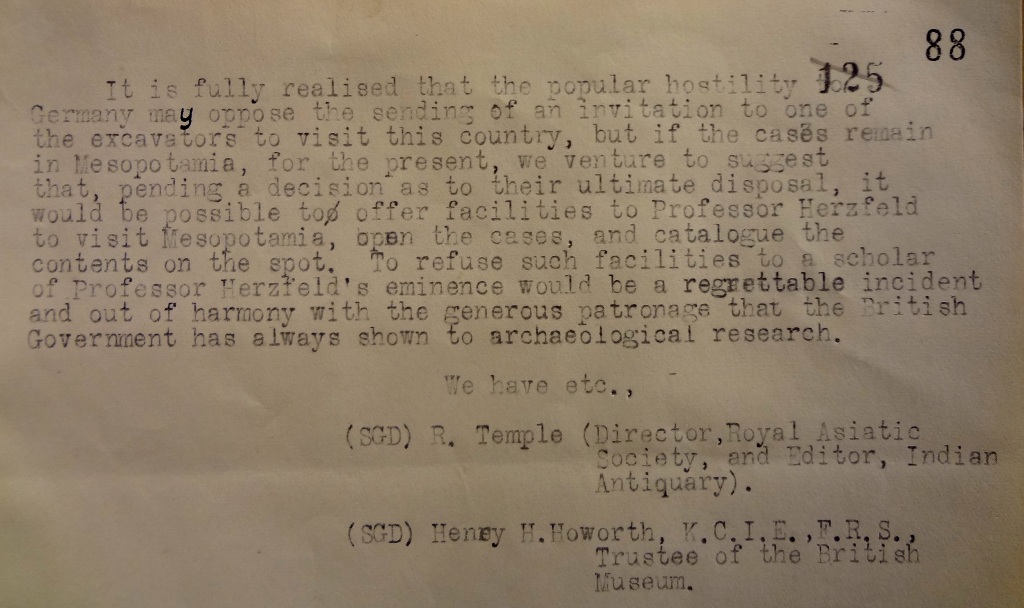

It wasn’t all that bad, though, and archaeologists sometimes remembered they were all animated by the same thirst for knowledge and desire to protect the invaluable remnants of the past. In 1920, some 90 cases of antiquities found in Basra during the British advance on Bagdad were sent to London as ‘a purely provisional measure designed to facilitate their preservation and study’. These artefacts had been discovered by German archaeologists Herzfeld and Sarre at Samarra, in Iraq, during the 1910-1913 seasons. A group of British archaeologists and orientalists wrote, in November 1920, to the Secretary of State for India demanding that Ernst Herzfeld should be present when the cases were opened (FO 371/4175).

British archaeologists and orientalists to the Secretary of State for India (catalogue reference: FO 371/4175)

Coming from a site of extreme importance for the study of the genesis of Islamic art, the antiquities were unique and in a rather unstable state. Without Herzfeld and his notes, it would probably have been impossible to preserve them. In June 1920, he was invited to proceed to London – archaeology had won the war.

[…] Peaceful archaeology […]

‘Students’ of the British School at Athens had been heavily involved with the mapping and recording of archaeological sites in Ottoman lands prior to the First World War. Hogarth himself had undertaken a series of travels through Anatolia, and was a great authority on the Near East. It needs to be remembered that a large number of archaeologists (many former students of the British School at Athens) were associated with the Arab Bureau (in Cairo) and related intelligence gathering operations. For more on this topic see my Sifting the Soil of Greece (2011)

http://bsahistory.blogspot.co.uk/2011/04/sifting-soil-of-greece.html

Thanks for your comment, David, and for the link to your blog and books. You are quite right – a lot of archaeologists were associated with intelligence gathering in the Middle East during the First World War. You can read more on this in my blog post on Digging for King and Country.