This blog, published as part of Cervical Screening Awareness Week (15-21 June 2020), looks at records held at The National Archives that provide insight into how and why cervical screening was established from the 1960s as a means to reduce cancer mortality in women.

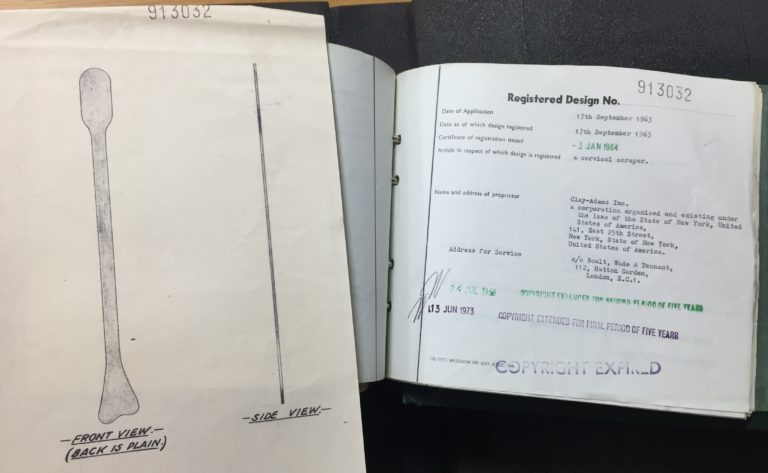

Cervical screening, or a smear test, involves exfoliating (or swabbing) cells from the cervix, and then sending the cells to a laboratory to identify whether any abnormal cells are present that could lead to cervical cancer.

From the mid-19th century researchers understood that cancerous cells could be identified under a microscope, which led to the development of exfoliative cytology – the study of cells for diagnostic purposes[ref]The study of cells as a diagnostic process can be traced back further to the likes of Alfred François Donné and Johannes Müller in the 19th century, see: A. Diamantis and E Magiorkinis, ‘Pioneers of exfoliative cytology in the 19th century: The predecessors of George Papanicolaou’, Cytopathology, 25, No.4, (August 2014)pp. 215-224.[/ref]. In 1928 George Papanicolaou showed that smears could identify abnormal cells found in the uterus. With the introduction of the Papanicolaou test in clinical trials in the 1950s (also referred to as the Pap test or the Pap smear), the identification of pre-cancerous cells from the cervix was made possible by a simple test, helping to identify women who were at risk even before cancer had developed.

Early screening of ‘Well Woman’

Cervical cancer screening programmes were being trialled in the US and Canada throughout the 1950s. By the early 1960s discussions began to take place about starting a screening programme in the UK, particularly as health policy began to shift towards policies that looked at preventative measures and non-communicable diseases such as cancer. Infectious diseases were beginning to be eradicated or brought under control; the 1950s and 60s had seen a successful mass X-ray campaign against tuberculosis and Lord Leatherhead remarked in the House of Lords that:

‘If a similar mass campaign on behalf of cervical cancer were carried on in the same serious mood we might meet with a similar degree of success. And in that event it could bring peace to millions of women; it could make many happier homes; it could save 3,000 lives a year, and prevent an enormous amount of suffering.'[ref]Extract from Hansard, 2 November 1965, vol. 269.[/ref]

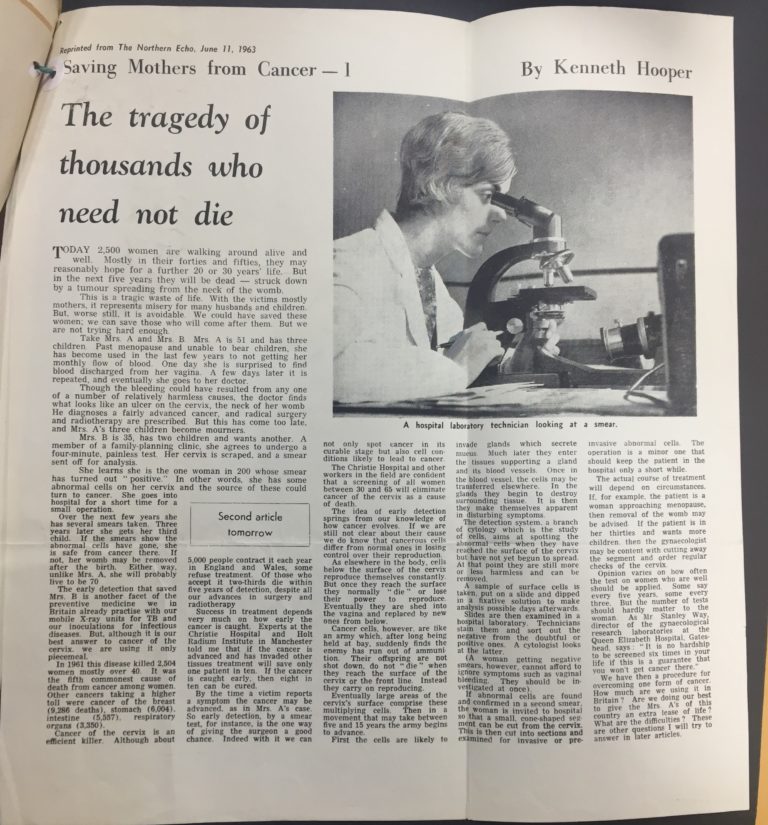

Some early advocates of cervical screening included Stanley Way, a Newcastle-based gynaecologist who had spent time in the USA, as well as the journalist Harold Evans, who started a public campaign in the newspaper The Northern Echo. There were also calls for the introduction of screening from public groups, such as Women’s Institutes, the Townswomen’s Guild, the National Council of Women, and the Women’s British Legion[ref]Ibid.[/ref].

Pilot schemes began to take place across the country. Two of the most developed were in Newcastle and South Wales[ref]BD 18/306, Welsh Hospital Board, Exfoliative cytology service: general correspondence 1961-66 and MH 160/85, Ministry of Health, Newcastle RHB cytology services: meeting notes and papers.[/ref]. In November 1963 the Ministry of Health issued a circular (HM 64 (70)) prompting Hospital Boards to allocate funding for cytology services. In order to make provisions for the service, the Ministry sought to expand the training of pathology laboratory staff, and five training centres were set up across the country: in Newcastle, Hammersmith, the United Birmingham Hospitals, the United Manchester Hospitals, and the Royal Free Hospital[ref]MH 160/85, Principal Regional Officers, Minutes of the Meeting, 6 October 1964.[/ref]. In December 1964 there were just 150 trained technicians; by June 1966 this had risen to 457 with another 145 in training[ref]RG 26/386, The Medical Officer, 4 November 1966, p. 249.[/ref].

Despite these efforts, the lack of trained specialists and health practitioners was an ongoing barrier for screening programmes[ref]For example, see: MH 160/85, Minutes of the Central Health Services Council, 8 October 1963, pp. 3-5 and MH 159/81 Cervical Cytology Service, Development Meeting, 4 October 1965.[/ref]. One solution, consistently put forward by Baronness Summerskill in the House of Lords, was to recruit married women doctors, who had left the field to look after their families, on a part-time basis[ref]Extract from Hansard, 2 November 1965, vol. 269.[/ref].

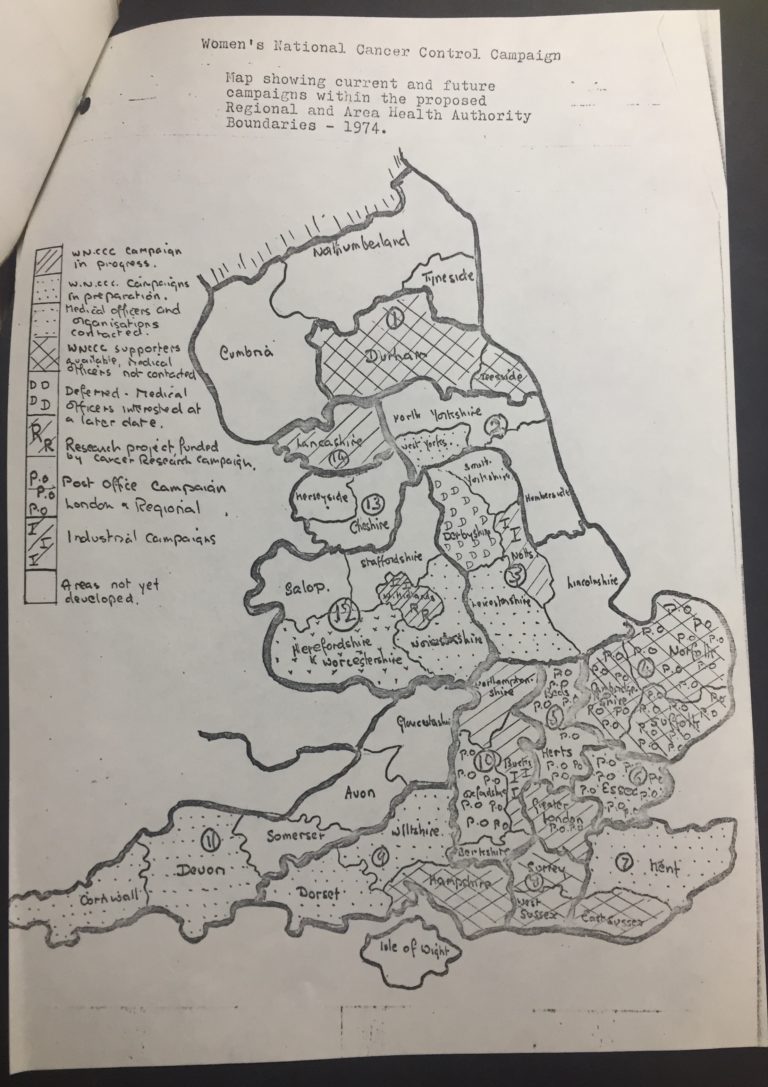

Screening varied considerably by location, as the centre did not provide any funds, and it was up to local authorities how they approached it. Some early schemes were carried out by volunteer health clinics, family planning centres, and even businesses. In 1965 Marks and Spencer, as part of its health welfare service for employees, introduced free cervical screening for women over the age of 35, extending it to women over the age of 25 in 1967[ref]L A Reynolds and E M Tansey (eds), History of cervical cancer and the role of human papillomavirus, 1960–2000, Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine (London, 2009), p. 89. See also, Marks and Spencers Company Archive.[/ref].

Expansion of the Cytology Service

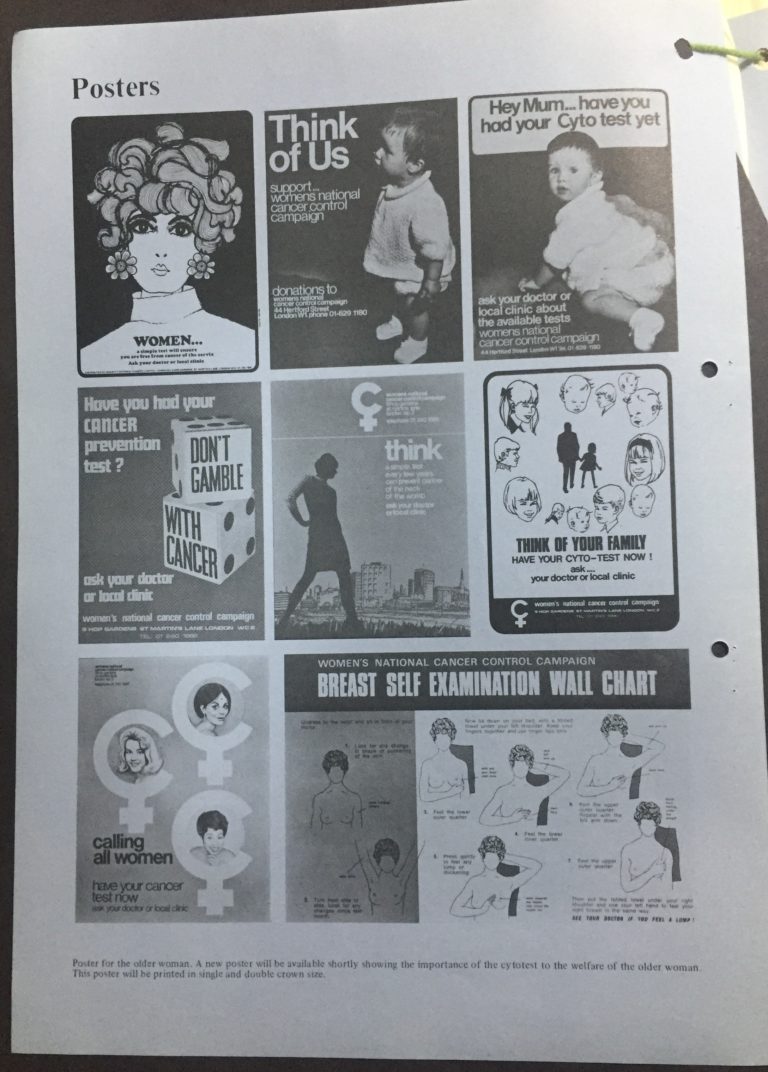

Cervical screening continued to expand haphazardly over the course of the next few decades. With ad hoc government support, volunteer services became integral in continuing the service. The Women’s National Cancer Control Campaign (WNCCC) was a national body, partly-funded by the Health Education Council in the early 1970s, that assisted health departments of local authorities with the organisation of educational campaigns, relating mainly to the prevention of breast, lung and cervical cancer. The WNCCC had two mobile units for cervical cancer cytology screening, staffed mainly by volunteers. In fact, ‘The units were entirely female staffed’, which helped targeting at risk women from lower socio-economic groups[ref]MH 154/484, ‘Notes of Meeting with Lady-Llewelyn-Davies, Chairman of the Women’s National Cancer Control Campaign’, 8 June 1973.[/ref].

Since its introduction the cytology service was marred by limitations and problems, including:

- Lack of funding and guidance from the government leading to haphazard organisation

- Ethical concerns about the over-treatment of pre-cancerous abnormalities, particularly as it turned out that some abnormalities could regress on their own

- Poor evidence of the reduction of mortality due to (1) difficulties in attracting women considered to be high risk; (2) the failure to implement national population-based screening. (Mortality was reduced in areas with successful screening programmes, such as Aberdeen)

- Hesitancy from general practitioners about implementing the service

- Administrative errors leading to abnormal results not being followed up, such as with the Kent and Canterbury Hospital’s cytology service in the 1990s

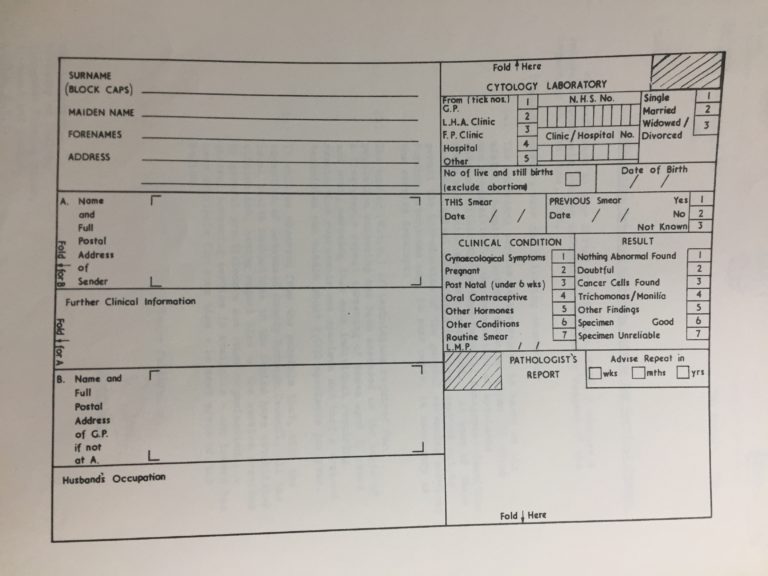

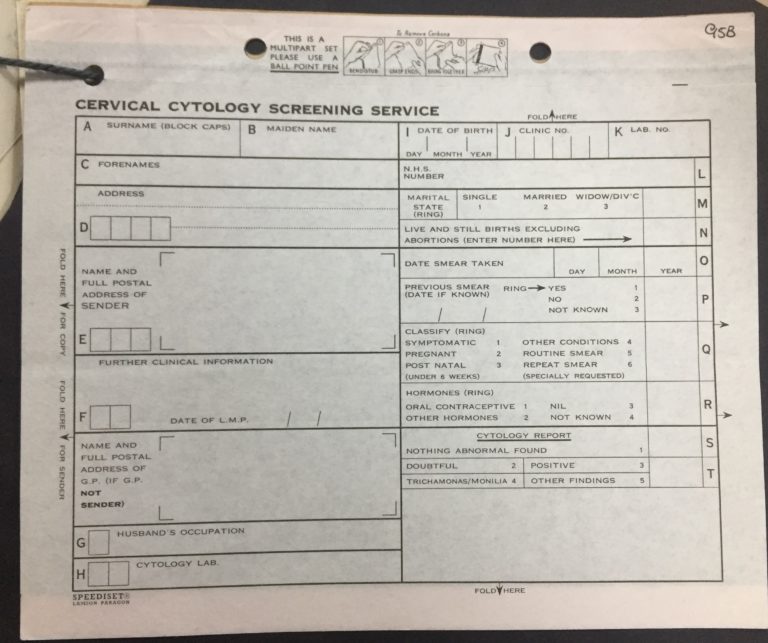

While little equipment was needed to carry out the actual tests, the accompanying administration of the scheme presented a problem – from the design and wording of the form, the cost of postage, the storage of files, to how to invite women for regular screening in the first place. Mr G W Jewkes of The General Register Office remarked on the high number of nuisances ‘which, whilst apparently trivial in relation to a single form, add up to a very considerable problem when thousands of forms have to be handled'[ref]RG 26/386, G W Jewkes, ‘Memo, Cervical Cytology – Recall’, 17 February 1967.[/ref]. Archival records from the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys (in department references RG 26) point to the difficulties faced in standardising procedures.

Cervical screening today

In the 1980s the Cytology Service’s failures were brought to wider attention with the publication of an anonymous editorial in the medical journal The Lancet, citing rising mortality rates, predominately due to the failure to administer a nationwide population-based scheme. As a result of increasing public dissatisfaction the government launched the National Health Service Cervical Screening Programme in 1988, which standardised processes and implemented a computerised call/recall system to invite women to get a smear[ref]A E Raffle, A Mackie, and J A Muir Gray, Screening: Evidence and Practice (Oxford, 2019), pp. 17-19.[/ref]. Mortality rates fell. Today women aged 25-49 are invited every three years, and women aged 50-64 years are invited every five years.

Understanding of the causes of cervical cancer has also developed since screening was first introduced. The Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) was established as a cause of cervical cancer in the 1980s (HPV is also linked to other forms of cancer, such as penile cancer and neck cancer). An HPV vaccination programme started in 2008, which was offered to girls and young women, and last year, this was extended to school-age boys.

Regular screening has helped save the lives of countless women and today it is estimated that 2,000 women are saved each year through the programme. Screening attendance, however, is currently at a 20-year low, despite estimates that if everyone attended screening regularly, 83% of cervical cancer cases could be prevented[ref]Public Health England, ‘PHE launches ‘Cervical Screening Saves Lives’, 5 March 2019.[/ref].

For more information

Cervical Screening Programme Overview, UK Government: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/cervical-screening-programme-overview

A E Raffle, A Mackie, and J A Muir Gray, Screening: Evidence and Practice (Oxford, 2019)

I Lowy, A Woman’s Disease: The history of cervical cancer (London, 2011)