It is generally accepted that primary sources detailing paupers’ experience of the 19th century are largely written about the poor rather than by them.

This is true. However, at The National Archives we estimate there to be thousands of documents written by paupers within our record series MH 12. These ego documents (meaning autobiographical writing) take the form of letters, petitions and signed depositions that came into the Local Government Board and its predecessors, the Poor Law Commission and the Poor Law Board. So within one (admittedly huge) record series we can find documents setting out the pauper experience written by paupers themselves.

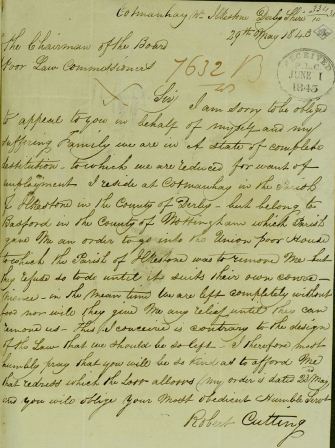

One letter that details the hardship of a family is MH 12/9233/164.

Image of a letter, dated 29 May 1843, to the Poor Law Commission asking for redress (catalogue reference: MH 12/9233/164)

In 1843 Robert Cutting wrote to the authorities in London asking for redress; he had been refused help by those charged locally with administering relief. The letter states that his family has been left without food. While no timescales are given, it is possible that Cutting’s family had been in this state since an order had been given for him to go into the workhouse, six days prior to his letter. As a starting point this letter shines a bright light into a very murky and opaque part of our history. From here researchers could look to see how the case was dealt with, using sources here at The National Archives or at local record offices (should the records survive). In addition, researchers could use the census to trace the family through time.

Another standout ego document is a petition (in MH 12/9234/41) that forms part of a fascinating report on an inquiry into complaints against the authorities of the Basford Union Workhouse. This is a copy of a petition, originally sent to a local newspaper, from paupers complaining about the treatment they had received. On reading it I was immediately struck by the fact that the inmates had written their names in a circle so that a ring-leader could not be established. If they had signed the petition as a conventional list the inmate who signed first (at the top) may have shown himself to be the ring leader and been seen as a ‘trouble maker’. This shows the perceived risk the inmates were taking in making their complaint.

Interestingly, when read in the context of the report we find it is possible that the complaint was part of a greater plan by the petitioners in league with a guardian, Mr Harrison, who is described as a ‘Chartist Preacher’.

![Petition signed in a circle by inmates of the Basford Union Workhouse (catalogue reference: MH 12/9234/41 [page 17 of the download])](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/01155957/petition-2.jpg)

Petition signed in a circle by inmates of the Basford Union Workhouse (catalogue reference: MH 12/9234/41 [page 17 of the download])

There is a catch though: they are not easy to find.

Parts of MH 12 are digitised and catalogued to item level[ref] 1. This means that a detailed description has been created for each piece of correspondence that was sent to authorities in London. [/ref] (we have a research guide that lists the records that are available in this format). This means that a small proportion of the pauper letters held here can be found by browsing the records in Discovery, our catalogue.

For unions that haven’t been digitised the only option is to leaf through volumes of MH 12 looking for letters that have been written by the poor. With volumes that are approximately 600 folios[ref] 2. A folio is an individual leaf of paper that is only numbered on the front side. This means that each MH 12 volume has approximately 1200 pages. [/ref] long this can be a daunting task.

However, there are signs to look out for. One sign is that letters written by paupers can be distinctive; often they are not on headed paper or the draft letter sheet used by the Poor Law Commission/Poor Law Board, and are usually smaller than the pages around them.

We are hosting a free workshop on 7 October to share what we have found so far. During the workshop myself, Professor Steven King (University of Leicester) and Principal Record Specialist Dr Paul Carter will put the pauper letters that we hold into context and discuss their significance. Most importantly however, through group exercises you will learn how to locate the ego documents that are buried within MH 12.

[…] for letters that have been written by the poor. With volumes that are approximately 600 folios 2 long this can be a daunting […]

[…] A pauper’s life in their own words […]

Hi, it’s great to see someone from a government department reflecting on pauper’s own words, needs to be far more. Well done and an enjoyable read.