Find your inner inventor at Spirit of Invention, a fun, free design exhibition at The National Archives opening on Saturday 27 May 2023 until Sunday 29 October 2023.

‘Art is pleasure, but invention is treasure. What is more important to society: a sheep in formaldehyde or a paperclip?’

Trevor Baylis, inventor of the clockwork radio

The point Trevor Baylis makes in this quotation is that inventors don’t have automatic rights over their ‘intellectual property’ in the way that artists, musicians and writers do.

Inventors have to go through a slow and expensive process of applying for a patent to show they ‘own’ an idea. And even then, if someone copies their invention they have to take them to court and risk losing large sums of money to challenge them.

The history of intellectual property – or the right to prevent others from copying your work – is a long and complicated one, and you will be glad to know I’m not going to attempt to go into it here. Instead, I want to explore how you can look at historical inventions recorded in documents at The National Archives.

Our original patent documents are not used very often, possibly because it takes a bit of detective work to find what you want, but also – we think – because people don’t realise what they offer.

Our research guide to Intellectual property: patents of invention explains how to find these records at The National Archives. In this blog I am going to illustrate the search process, using a specific invention, patented by Victorian photography pioneer William Henry Fox Talbot in 1843 as an example.

Background

Our records of patents start in the 17th century, at which time inventors applied for patents through the Court of Chancery. This carried on until 1852 when the Patent Office was established, and our patent records finish around this time.

You can also find details of patents in the British Library. They are easy to access and include inventions from before and after the creation of the Patent Office. However, the illustrations are not in colour, and often not as detailed as those in our collections.

There are two different elements to the records created in the patenting process:

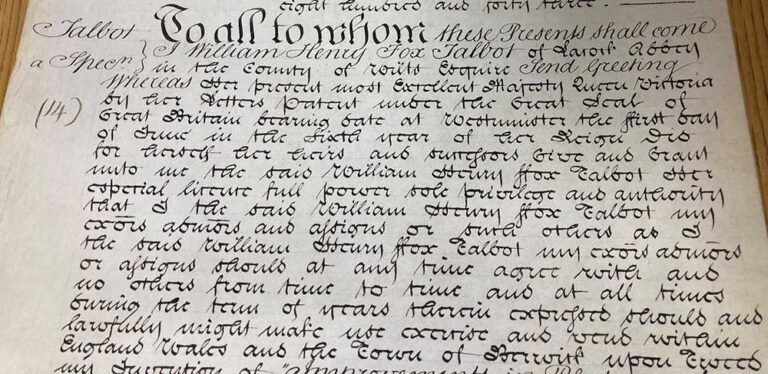

- the patent – this was a formulaic text which expressed the rights of the patentee to the invention, their name and the date the patent was granted

- the specification – this was where the details of the invention were carefully described. If anyone tried to copy the invention without permission, the patentee could show that they had the sole rights.

Of the two documents, the specification is the more interesting so I’m going to look at how I found the specification for one of William Henry Fox Talbot’s inventions.

Bennet Woodcroft

If you want to research inventors or inventions at The National Archives, the best place to start is in the second floor reading room (also known as the Map and Large Document reading room). To enter the room, you will need a reader’s ticket.

There you can find a series of books by Bennet Woodcroft which include:

- An Alphabetical Index of Patentees of Inventions – where you can look a person up by name and see what patents they registered

- Subject-Matter Index of Patents of Invention – where you can look up different areas of technology such as ‘brewing and distilling’, ‘light and lighting’ or ‘musical instruments’ and see what patents were registered and by whom

- Reference Index of Patents of Invention – where you can look up a patent using its specific patent number

The books cover the period 1617–1852 which is the period before the Patent Office was established and when the Court of Chancery was still the place to apply for patents.

Alphabetical and Reference indexes

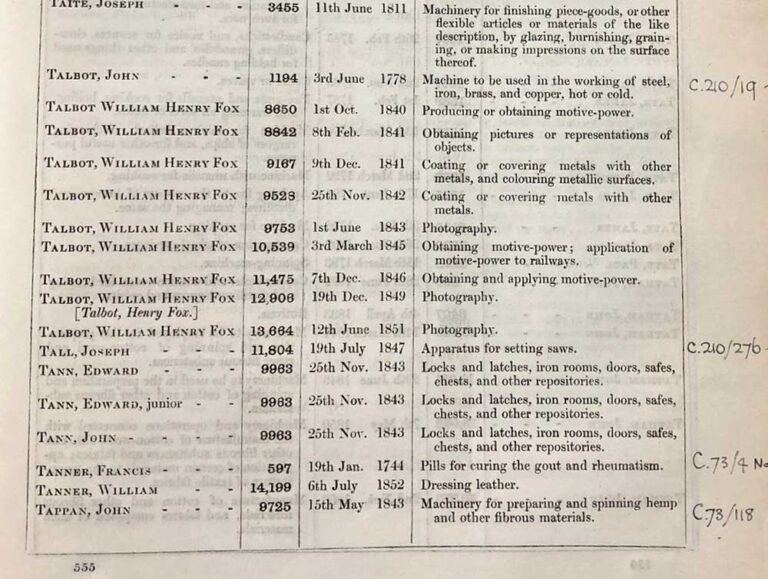

To find out about Fox Talbot I began with the Bennet Woodcroft Alphabetical index. The index shows he took out nine patents, six of which related to photography and three to motive-power.

The entries in the Alphabetical index show the date the patent was ‘enrolled’ and the number given to it (i.e. the patent number). For this example we’re going to see how to find the specification relating to patent number 9753 dated 1 June 1843.

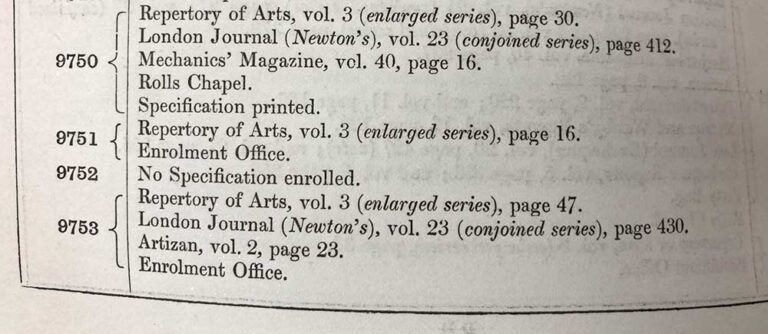

Now switching from the alphabetical to the reference index, I looked up the entry for patent number 9753. This shows the different places that information about the patent was published and the place where the details of the invention (the specification) were ‘enrolled’.

As explained in the research guide mentioned earlier, specifications were enrolled in one of three different government offices – the Enrolment Office, Rolls Chapel or Petty Bag Office. In this case it was the Enrolment Office.

Specifications for inventions in the ‘close rolls’

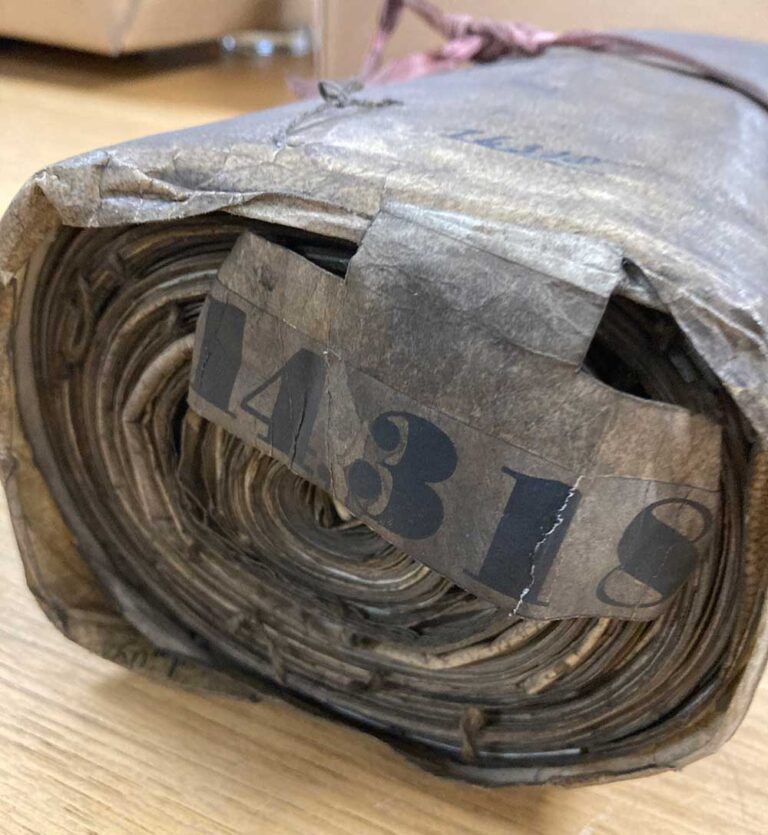

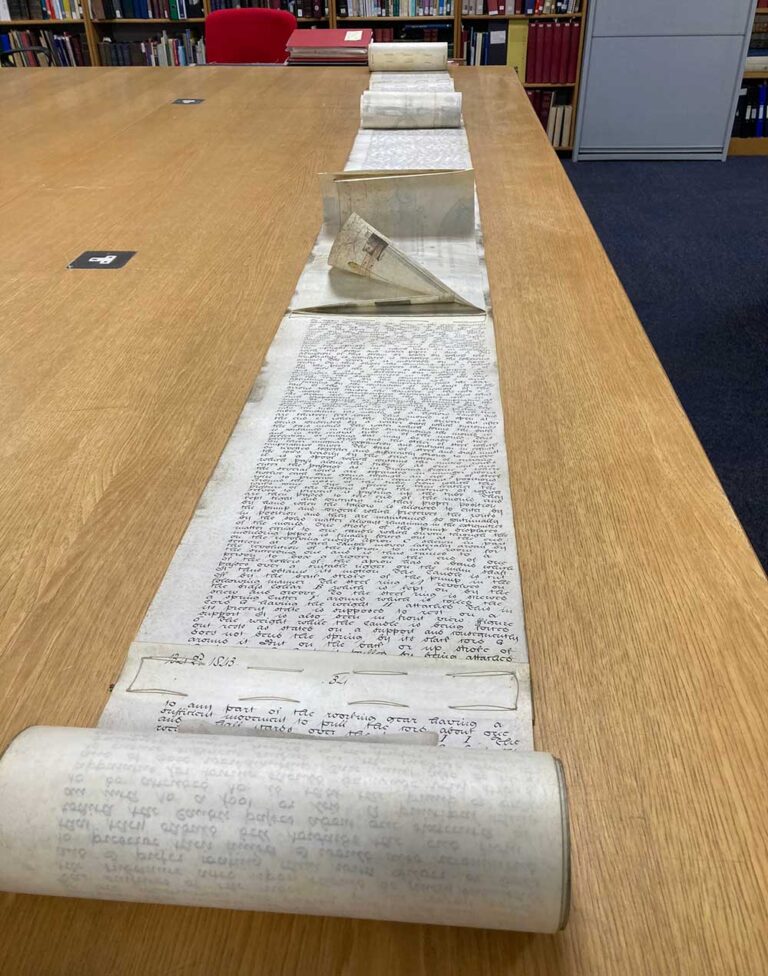

Specifications enrolled in the Enrolment Office are part of the Close Rolls. These are parchment documents covering a variety of matters, not just specifications. The documents are stitched together end to end and then rolled up – a bit like a roll of kitchen paper towels.

There are over 20,000 close rolls and together they form the record series C 54,. They cover a 700-year period, and each roll has a unique ‘piece number’ shown on a label attached to the roll.

At the moment there is no database showing which close rolls contain which patent specifications. Instead, the process is very old school – using hand-written indexes that are only available on site at The National Archives.

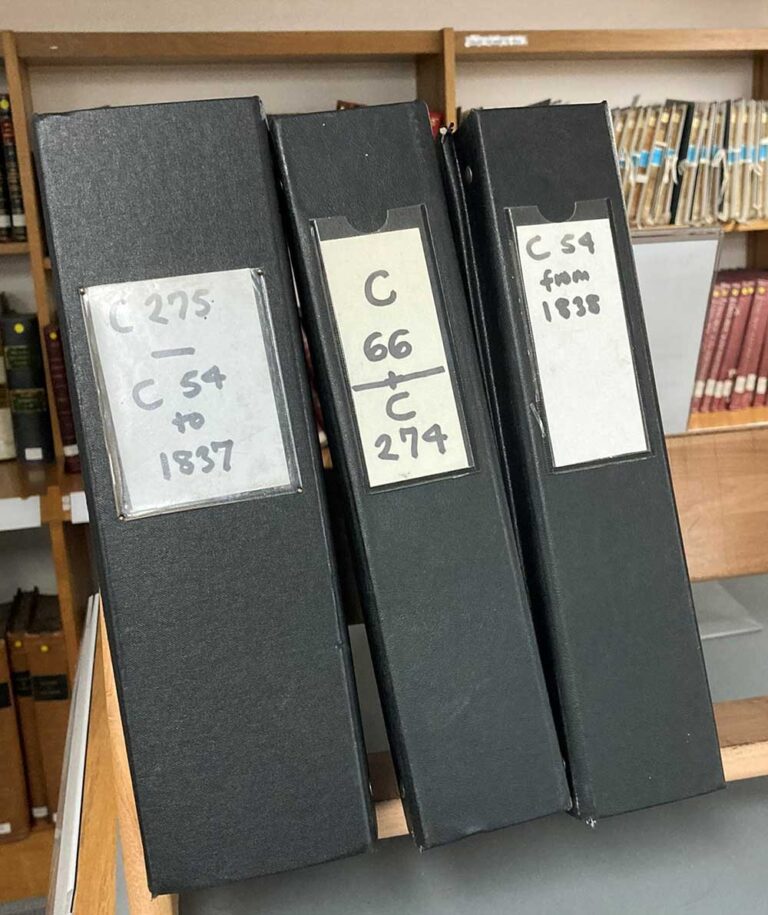

Indexes in record series C 275

The indexes are original documents that were created by the clerks working in the Court of Chancery to help them locate specific items in their offices. There are lots of original indexes kept on shelves in the second floor reading room, but the ones that relate to the close rolls in record series C 54 are

- C 275/209 covering 1617 to 1826

- C 275/210 covering 1826 to 1845

- C 275/211 covering 1845 to 1853

The last index goes up to 1853, even though our patent records end in 1852. This is because inventors enrolled their patents first, followed later by the specification. This means that sometimes the specifications weren’t enrolled until the following year.

Each index is organised first by year, and then alphabetically by the first letter of the surname of the inventors.

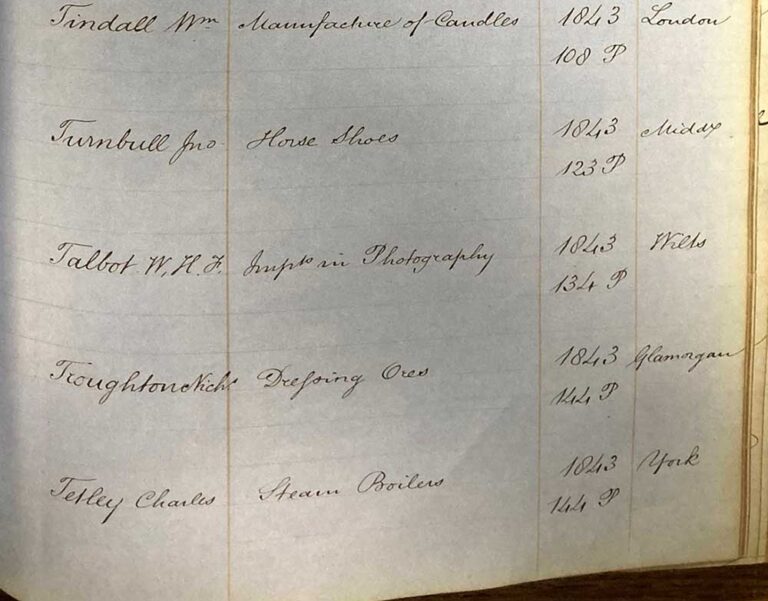

Using the index covering 1843, I found the entry for Talbot. It shows the invention described as Impts (improvements) in Photography and in the final column it shows Wilts (Wiltshire). However, the detail I needed was the part number (134) shown in the third column.

Finding the close rolls piece number

The process involves lots of moving between different indexes and references so just to summarise what I’d done up to this point:

- Looked up Fox Talbot in the Bennet Woodcroft alphabetical index and found nine inventions including one from 1843 which had the patent number 9753 (in bold)

- Looked up the number 9753 in the Bennet Woodcroft reference index and found it was enrolled in the Enrolment Office, meaning it was part of the close rolls in record series C 54

- Looked in an index to the close rolls for the year 1843 and found Fox Talbot’s entry showing the part number 134.

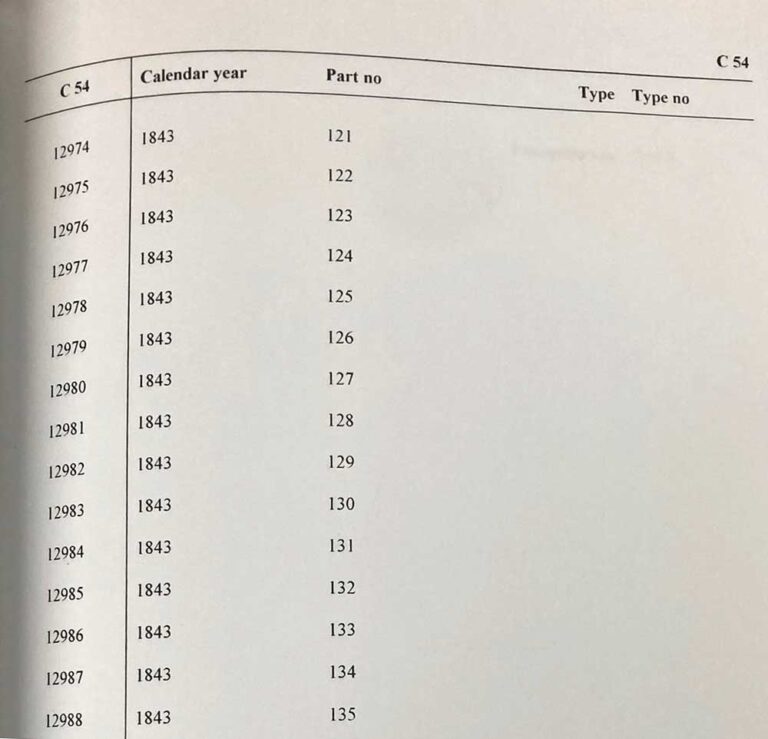

Now I needed to locate the relevant piece number in the close rolls or record series C 54. To do this, I used the printed list of pieces which is in a black binder on top of the shelves of indexes.

Within the binder the pages are arranged by year, and within each year the ‘part numbers’ are shown in order. I found 1843 and part number 134, and then read across to the left-hand column where it showed the C 54 piece number 12987.

Every document in The National Archives has a ‘document reference’ which identifies it from the millions of other documents in our collections. By putting together the record series number C 54 and the piece number 12987 into the format C 54/12987 we get the document reference for the close roll with Fox Talbot’s invention.

So finally, I ordered the close roll C 54/12987 and was able to see the specification for Fox Talbot’s patented process for improvements to photography. The specification lists nine different ‘parts’ and covers over four sections of parchment, stitched together. There are no drawings but each part of Fox Talbot’s invention is described in detail.

Fox Talbot caused controversy during his lifetime, with many feeling his patents and litigious actions were standing in the way of developments in the field. Knowing we also have records of legal disputes, I searched our catalogue for mentions of ‘Fox Talbot’ in the 1840s and 1850s and found descriptions of documents relating to legal disputes between Fox Talbot, James Henderson and brothers Richard and Lebbeus Colls.

Conclusion

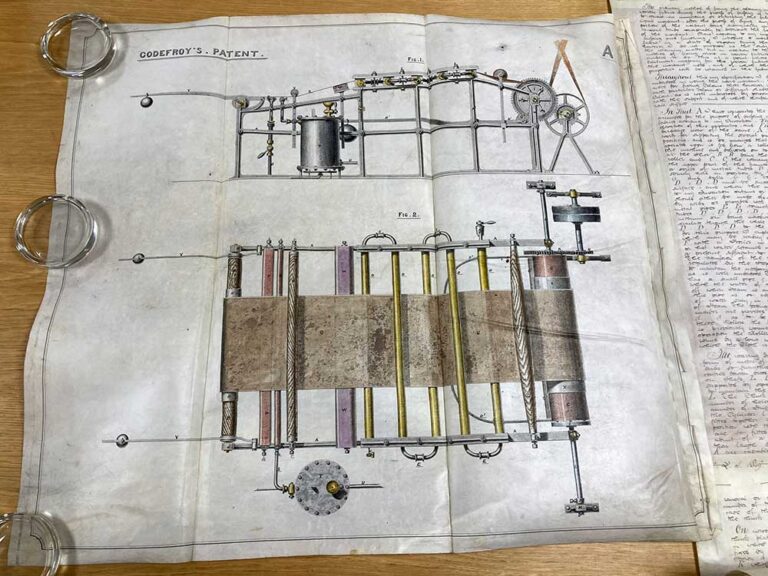

Exploring The National Archives’ patents and specifications has the potential for serendipitous moments. You can order a close roll with the intention of looking at the details of a particular invention, and then start unrolling it only to find a number of beautiful drawings that intrigue you and take you down another path.

Or maybe you try searching for an inventor in our catalogue and spot new avenues of research to get drawn into. Whatever the reason you might have for exploring these collections I hope you enjoy it.

Find your inner inventor at Spirit of Invention, a fun, free design exhibition at The National Archives open until Sunday 29 October 2023.