In 1895 Oscar Wilde had two successful plays in the West End: ‘The Importance of being Earnest’ had opened at the St James’s Theatre on 14 February and ‘An Ideal Husband’ was enjoying a successful run at the Haymarket Theatre. Wilde was at the height of his fame and success.

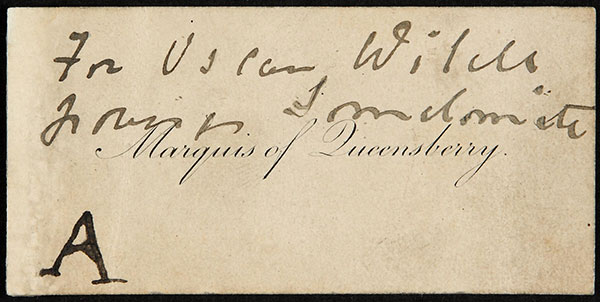

Exhibit A: Queensbury’s calling card. Catalogue reference CRIM 1/41/6

On 18 February the Marquis of Queensbury left his calling card at the Albemarle Club, endorsed ‘For Oscar Wilde posing Somdomite’ (Catalogue reference CRIM 1/41/6). Wilde did not receive the message until the 28 February. He then made the fateful decision to prosecute Lord Queensbury. Wilde lost the libel case in March – he was arrested on 5 April and his first trial began on 26 April; however, the jury were unable to reach a verdict. The Solicitor-General refused to halt further proceedings and a retrial went ahead from 22 to 25 May.

On 25 May 1895 Wilde was convicted at the Central Criminal Court of gross indecency and sentenced to two years’ hard labour. This was the maximum sentence allowed, which was considered excessive for a man of his class at that time.

The National Archives has an important collection of records relating to the trials and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde among the papers of the Home Office (HO), the Central Criminal Court (CRIM) and the Prison Commission (PCOM). Unfortunately, no shorthand notes or transcription of the trial proceedings have survived. However, the trials were widely reported in the press, and detailed accounts of the proceedings in the newspapers were used to reconstruct the trials by H Montgomery Hyde in his book ‘The Trials of Oscar Wilde’, originally published in 1948. A podcast by Charles Tattersall, Genius on trial: key sources relating to Oscar Wilde at The National Archives is available to listen to on our Archives Media Player.

Sent first to Pentonville, Wilde was passed as fit for light labour: oakum-picking, sewing mailbags, working the crank and the treadmill. He was kept in solitary confinement and the food and conditions began to have an effect on his health. He was moved to Wandsworth in July and had the ignominy of having to attend the Bankruptcy Court on 24 September and again on 12 November. In the meantime, his health completely broke down and he suffered a serious fall in his cell. Wilde was then moved again from Wandsworth to Reading on 21 November – on this day he was forced to wait for the Reading train on the platform at Clapham Junction, where he was recognised and abused by the crowd.

In Reading Gaol he petitioned the Home Secretary on 2 July 1896 (HO 45/24515). There was no reply to the petition and no mitigation of his sentence. The Prison Commissioners, however, did authorise more books and allowed him additional writing materials (PCOM 8/433). While in prison in 1897 he wrote ‘De Profundis’ his letter to Lord Alfred Douglas. He asked the governor for it to be sent to Douglas, and Major Nelson wrote to the Prison Commissioners (PCOM 8/434), but the request was refused. Nelson kept the manuscript and gave it to Wilde on his release. Wilde sent two further unsuccessful petitions in November 1896 and April 1897. In the third he asked for his release date to be brought forward by just four days to 15 May to avoid unwanted attention. Although not agreed to, arrangements were made to move him from Reading back to Pentonville on 18 May and he was released at 06:15 on 19 May 1897. After a brief morning reunion with friends, he left for Newhaven that afternoon and caught the night boat to Dieppe. He was never to see England again.

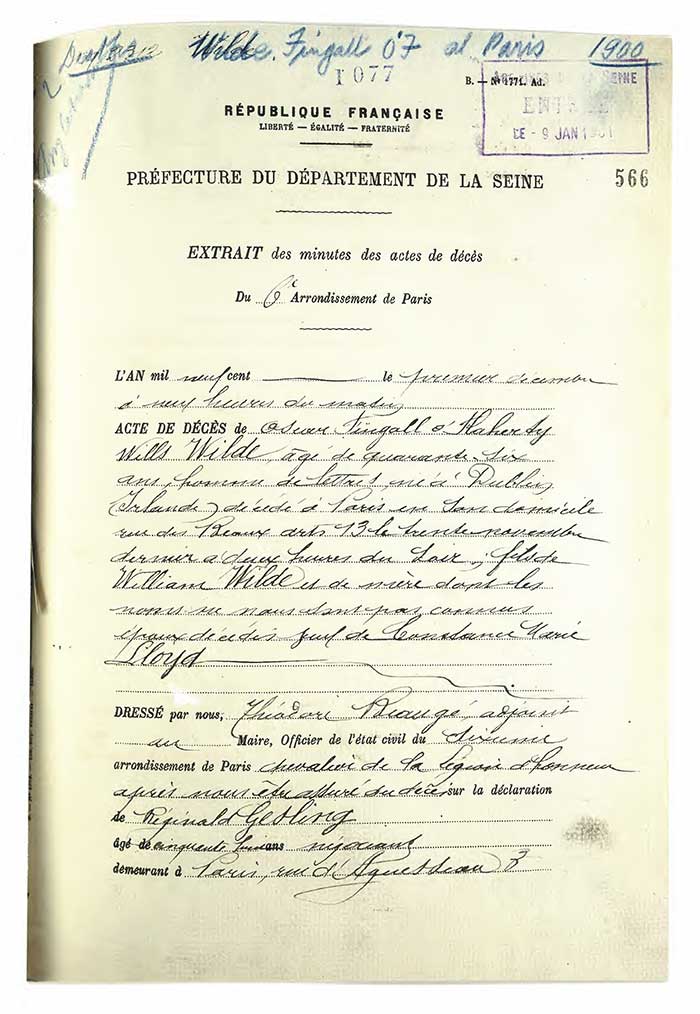

In Berneval he began working on ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’. In August he had a reunion in Rouen with Douglas and they went to live in Naples, but by the end of December their relationship was over. ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’ was published in February 1898 the author’s name being replaced by C.3.3 the number of his cell. Wilde spent the next two years wandering around Europe with sojourns in Switzerland, the south of France and Rome. However, he returned time and time again to Paris, where he eventually died from cerebral meningitis in the Hotel d’Alsace on 30 November 1900. A copy of his death certificate was returned to the General Register Office in London via the British Embassy in Paris (RG 35/35 f. 566).

Wilde’s death certificate. Catalogue reference RG 35/35 f. 566

As Michael Taylor wrote in ‘Oscar Wilde: Trial and Punishment, 1895-1897’:

Any student of late-nineteenth-century culture is amazed to see how quickly the rich cultural diversity of the 1890s evaporates, and it seems likely that Wilde’s downfall played a major part in this process.[ref]‘Oscar Wilde: Trial and Punishment, 1895-1897’ (London: Public Record Office, 1997)[/ref]

Related resources

In 2016, some of our staff created a short play using documents from our collection. ‘Suffering is one very long moment: The imprisonment of Oscar Wilde’ used words taken directly from the records.

To find records relating to sexuality and gender identity history, use our research guide.

No criticism intended, but the spelling is Queensberry. As it says on the card.

Reading prison records say he was transferred on the 20th.