The Close and Patent Rolls are two different types of administrative record of the English royal government. Both were begun in the early 13th century. The Close Rolls ceased to be used by the early 20th century, but the Patent Rolls have continued and are still in use today. Almost all of them survive, with The National Archives holding more than 26,000 such rolls.

Close rolls at The National Archives

The rolls contain copies of the letters sent out in the king’s name during a given period (each usually covered one year of a monarch’s reign, or part of one year) which were summarised and written on to membranes of parchment sewn head to head, generally in reverse chronological order, and then rolled up. Letters patent, from the Latin patens, meaning open, are exactly that. They were usually something like a published written grant or order, expressing the monarch’s will on a variety of matters of public interest, authenticated with the Great Seal, and which were to be publicly proclaimed. Appointments to hold office are among the most popular, for example, or as here, acknowledgements of the king’s debts.

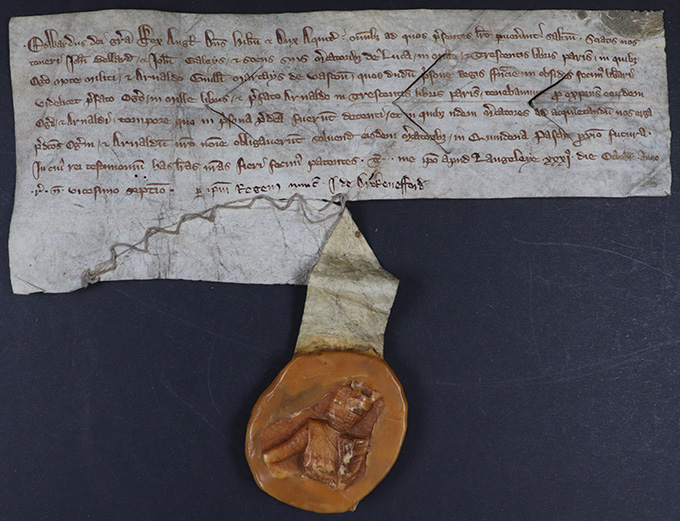

E 156/28/14 – letters patent acknowledging that King Edward I owes John Ballard and John Galeys and their fellows, merchants of Lucca, £1,300 Paris, which the King caused them to deliver to Oger Mote, knight, and to Arnald Guillelmi Marcays of Gascony while hostages in the prison of the King of France, namely £1,000 to Oger and £300 to Arnald, to be repaid a fortnight after Easter next. By the King on the information of J. de Drokenford. Dated at Kings Langley, 31 October 1299

Letters close were almost the opposite. Pertaining more often to matters of a private or personal nature, they were designed only to be read – and the seal by which they were closed shut, broken – by their addressee. For example, letters patent might be issued to royal judges holding pleas around the country where it would be necessary for any involved to know that this came with the monarch’s authority, while letters close might be issued to someone who was to take 20 oaks from a royal forest, which only the king’s forester needed to know about. The matters discussed within both these types of documents are very wide-ranging and diverse, covering all aspects of medieval royal administration and government.

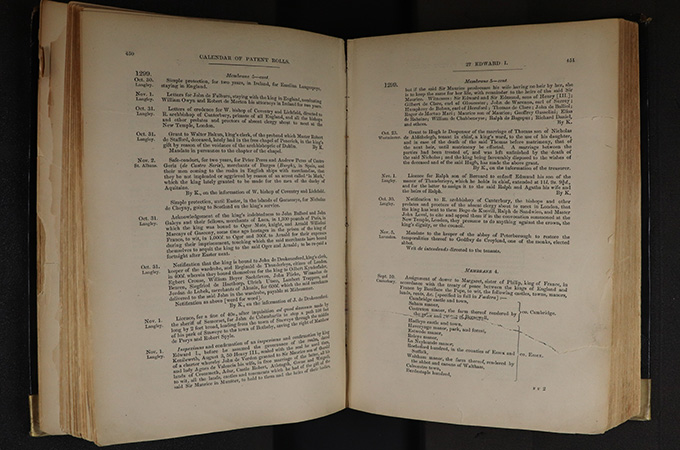

As a student intern researcher for The Northern Way project – a collaboration between the University of York, The National Archives and York Minster – I have been working with the late 19th- and 20th-century ‘Calendars’ of these two sets of rolls. Printed in book form by Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, these valuable resources are now also available online (Patent Rolls and Close Rolls) and provide well-indexed, short but comprehensive, English summaries of the material from the original rolls. This makes them a lot easier to access, navigate, and read, than a large cumbersome roll handwritten in Latin.

Having seen an actual patent roll (series C 66) at The National Archives, I’m very grateful to those who prepared these Calendars; they are relatively easy to use and written in a language which, though sometimes technical, is easy to understand and interpret, as you can see in the entry for the letters patent pictured above.

Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1292-1301, p. 450

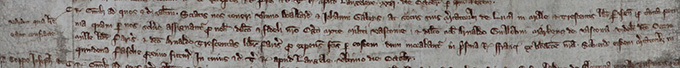

Trying to mine the original patent roll for the same information would have been incredibly laborious and lengthy by comparison, as the entries on each roll are close together, written in a small hand with no easy, reliable means of reference like an index, and only very brief headings in the margin for guidance.

C 66/119, membrane 5 – note the reference to the cancellation of these letters because they have been broken; this is marked in the original by the three slits cut into the parchment

I had never worked with these documents before and their peculiarities can take some getting used to. But, once familiar, the wealth and variety of information contained within is invaluable.

I have been looking at the rolls from 1398 to 1405, during Richard le Scrope’s tenure as archbishop of York. Archbishop Scrope was a highly controversial figure whose northern rebellion against Henry IV in 1405 ended with his execution[ref]Richard Scrope: Archbishop, Rebel, Martyr, ed. P J P Goldberg (Donington, 2007)[/ref].

The contents of the calendars relating to his period as archbishop here range from the rather repetitive and mundane confirmations of appointments to various offices, particularly to prebends (a benefice – the share of the revenues of a cathedral or collegiate church granted to a canon or member of the chapter) within York Minster, to some very juicy gossip. There are details of excommunications, summonses to parliaments, bridge-building instructions and even a compulsory purchase of wax for unspecified reasons.

I restricted my search to material relating specifically to Archbishop Scrope, but even within this narrow focus the results covered such an array of persons and interests that they show how these rolls could be used by any researchers for almost any purpose.

These rolls can highlight incidental detail about the material culture of the period. For example, there is one entry (CPR 1401-5, p. 50), where John Elvet, a clerk of Henry IV, gave to the king a golden chaplet covered in jewels, including 144 pearls and 150 diamonds. However, it notes that nine of these diamonds were counterfeit. This isn’t entirely relevant to the entry, which is chiefly concerned with matters of finance between Archbishop Scrope, King Henry IV, and the Earl of Northumberland, but clearly someone had spotted these forgeries in a chaplet heavily jewelled with genuine precious stones and it was being noted, perhaps as a black mark against Elvet. The inspector must have been quite thorough to pick up nine fakes among 141 genuine diamonds.

Another fascinating tale is that of born-and-bred Yorkshireman Nicholas Bubwith. Bubwith had a career in Chancery, eventually rising to move through several senior ecclesiastical posts, including Bishop of London, Bishop of Salisbury, and finally Bishop of Bath and Wells, in which post he died in 1424. But before this success it seems that he had a tricky time trying to take up a post.

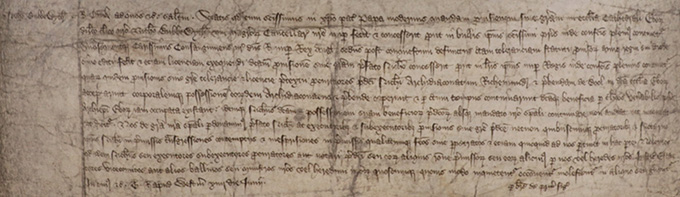

An entry in the patent rolls dating from 1400 states that Pope Boniface IX made a provision of the archdeaconry of Richmond to Bubwith, and Richard II granted licence for the execution of this. Bubwith accordingly took possession of this and the prebend of Bole, but these offices were occupied by clerks of the archbishop of York, and the roll states that Bubwith ‘dares not continue his possession’. The king pardoned him the trespasses in this.

A year later a licence was issued for Bubwith to sue his right to the archdeaconry of Richmond in the Court Christian and continue his possession. And a year after that Bubwith was again granted the archdeaconry of Richmond, with a mandate to Archbishop Scrope and the dean and chapter of York.

Then in the Archbishop’s Register (YDA Abp Reg 16), dated not even two months later, Stephen le Scrope junior, the nephew of the archbishop, is confirmed as the archdeacon, following the resignation of Bubwith in exchange for the prebend of Driffield. A fierce tussle for this office seems to have taken place with Archbishop Scrope eventually winning out, conceding a prebend in exchange for his nepotistic goal.

The exchanges have been recorded in the Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae but no detail of why this happened is mentioned. In Bubwith’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography his brief holding of the archdeaconry is touched upon, but this much more complex story is not explored fully.

C 66/354, membrane 1 – pardon to Nicholas Bubwith, master of Chancery, for taking possession of the archdeaconry of Richmond and the prebend of Bole in York Minster, 14 June 1400: CPR 1399-1401, p. 43

By working across the Patent Rolls and Archbishop Scrope’s Register, we can gain a much fuller understanding of what occurred than we ever could by using either in isolation. We see two kings, Richard II and Henry IV, intervening in a dispute that had gone as far as the pope, as the ultimate arbiter. The involvement of the hand of the archbishop of York is closely felt through this struggle, so we can see how his business stretched across the country and to as far as Rome in dealing with a matter specific to the northern Church. Local and national documents reveal how this involved figures whose realms ranged from all of Christendom down to a few prebends in Yorkshire. This enables us to understand more fully how far-reaching the consequences were of both cooperation and conflict between Church and State and how these decisions affected so many lives.

Stephen Huws has recently completed an MA in Medieval Studies at the University of York. The research for this blog post was undertaken while an intern on The Northern Way project at the University of York and The National Archives.

Bibliography

- The National Archives, C 66/347-375 (Patent Rolls) and C 54/240-254 (Close Rolls)

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1396-1408, four volumes (London, 1903-09)

- Calendar of Close Rolls, 1396-1409, four volumes (London, 1927-31)

- York Diocesan Archive, Archbishop’s Register 16, f. 9 (verso), entry 1 [Accessed: 10 Jul 2019]

- John le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541, VI: Northern Province (York, Carlisle and Durham), ed. B Jones (London, 1963)

- ‘Bubwith, Nicholas (c. 1355–1424), administrator and bishop of Bath and Wells.’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 12 July 2019

[1] Richard Scrope: Archbishop, Rebel, Martyr, ed. P J P Goldberg (Donington, 2007)