Ernest Bevin catalogue reference: INF 14/20

4 April 2019 marks the 70th anniversary of the signing of the treaty that brought NATO into being.

Ernest Bevin was the British Foreign Secretary. He believed that co-operation between the nations bordering the North Atlantic was essential to protect against the threat of an attack by the Soviet Union, and to contain communist expansion. Bevin’s vision was to create a union of the transatlantic nations that would provide effective military and economic security for the future.

To achieve this, he believed that it was essential for the United States to be involved in the defence of Europe. Bevin became a driving force behind the process that would culminate in the signing of the treaty in Washington and the creation of NATO.

The process began with the signing of the Treaty of Dunkirk between Britain and France in March 1947. This was a bilateral agreement designed to prevent a resurgence of German militarism; it established a new, Anglo-French military alliance to last for 50 years. The next step, Bevin realised, was to convince the Americans that Europe was prepared to do more in respect of its own defence. This led to the formation of the Western European Union, which included the Benelux countries of Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, as well as Britain and France.

In an impassioned speech in the House of Commons in January 1948, Bevin argued that the establishment of a defence pact between the countries of Western Europe was essential to guard against the threat posed by the Soviet Union. Negotiations between the five nations of the Western Union resulted in the signing of the Brussels Treaty on 17 March 1948.

In mid-July 1948, the French Government fell: France was without a government for two months. Germany was still in upheaval following the war, and had no central government. Bevin emerged as the one Western European political leader who had the strength to carry his country with him and represent European interests with – and if necessary against – the Americans. He came away from The Brussel Pact’s Consultative Committee meeting in The Hague on 19 and 20 July more than ever convinced that no purely European organisation would have the strength to succeed on its own. Britain, however involved with Europe she might be, must look for her security within an Atlantic framework, rather than a purely European one.

The Brussels Treaty had a positive reception in Washington: Bevin continued to press both the United States and Canada to begin talks on collective security in the Atlantic and Mediterranean. In July 1948, exploratory talks began in Washington, with Sir Oliver Franks representing British interests.

Major differences soon began to emerge. Bevin’s main concern was that the Americans should commit themselves to supplying arms and equipment. However, the United States insisted that there would have to be co-ordination and standardisation of military planning by the European states before any such commitment could be made. The United States was not going to commit itself to unilaterally supplying military resources in order to guarantee European security.

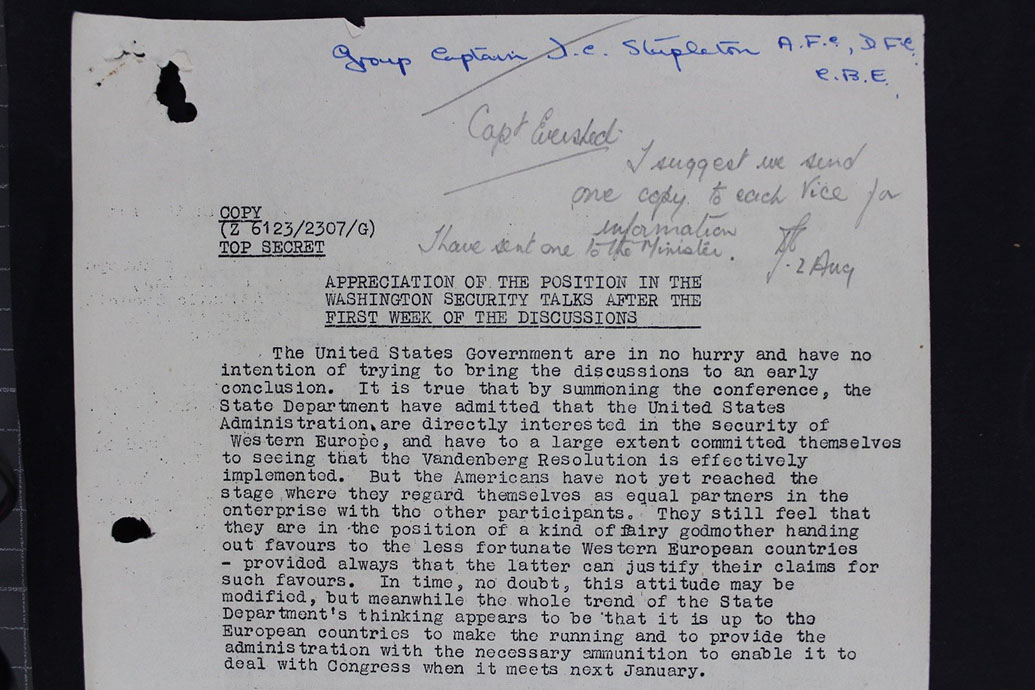

Sir Oliver Franks summed up the situation when he argued that the Americans were behaving as if they were a ‘kind of fairy godmother handing out favours to the less fortunate Western European Countries – provided always the latter can justify their claims for such favours’ (DEFE 11/19).

North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) military. Catalogue reference: DEFE 11/19

A further bone of contention was the size and geographical coverage of the proposed alliance. The United States wanted to extend the alliance beyond the Brussels Treaty states and include all nations bordering the Atlantic. They proposed that Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Iceland, Ireland, and Portugal be included. Britain, with the other Brussels Treaty members, felt that any extension of the proposed alliance would weaken it and diminish its effectiveness.

The wording of the obligation for one member state to come to the aid of another if attacked also proved controversial. The Europeans favoured an agreement similar to Article 4 of the Brussels Treaty, under which members of the alliance agreed to give the party attacked all the military assistance in their power. However, the Americans insisted that any response by the United States to an attack would have to be authorised by the President and/or Congress. In September 1948 the talks were suspended, pending the outcome of the Presidential election.

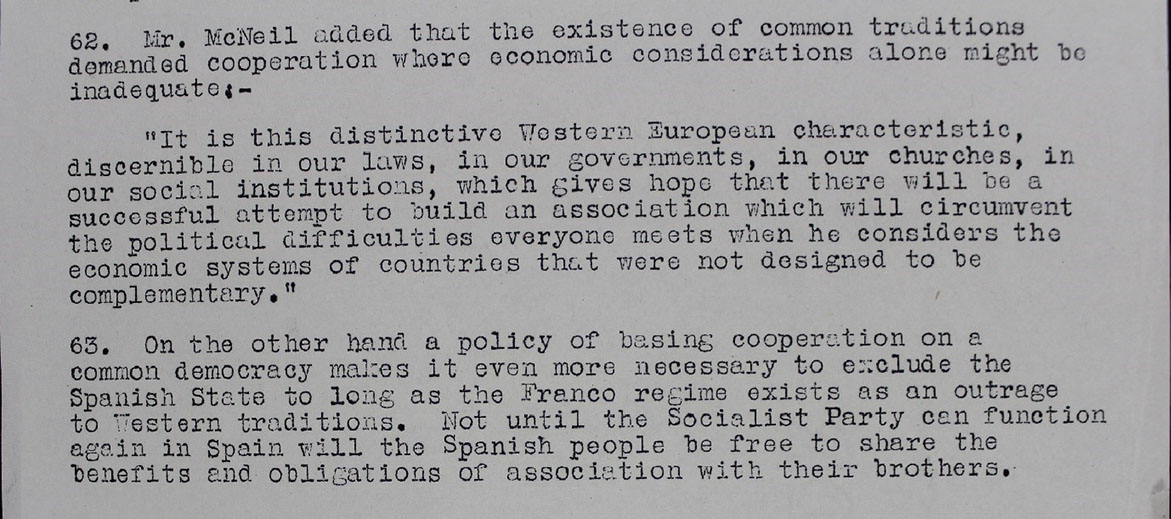

The following November saw the re-election of Truman as President of America. During his campaign, Truman had stressed the importance of containing the threat of Soviet expansion: he saw the creation of a transatlantic security pact as an essential part of achieving this. The talks were immediately resumed; eventually it was accepted that the alliance would need to extend beyond the Brussels Treaty powers. The governments of Denmark, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Portugal and Sweden were invited to participate: only Ireland and Sweden declined to do so. The inclusion of Spain was rejected. This was on the grounds that – as Denis Healey, the Labour Party’s International Secretary, argued – Spain could not participate in the work of co-operative recovery until its people were freed from the Franco regime (FO 371/71808).

ERP British Labour Party views on European cooperation. Catalogue reference: FO 371/71808

The United States believed that membership of the Alliance would strengthen their ties with the West and protect them from communist subversion. They proposed the inclusion of Italy, and other nations such as Greece and Turkey that did not border the North Atlantic. The European powers were very much against the inclusion of Italy: they felt that that she would be a military liability for some time to come. However, the need to keep Italy within the western fold outweighed such military reservations and she would become the 12th state to sign the original Treaty. Greece and Turkey became members in 1951.

A draft treaty was prepared and circulated to the governments in December 1948. The main problem rested with the pledge of mutual assistance: the Europeans wanted it to be as strong as possible but the United States insisted that any deployment of American troops should be a decision for the President alone. In an attempt to satisfy both parties, Article 5 of the draft treaty set out that an attack against one member would be considered an attack against them all. In the event of such an attack, each member would assist the party, or parties, so attacked. This would be in accordance with the right of individual, or collective, self-defence – as recognised under Article 51 of the United Nations Charter. They would take such individual or collective military action as might be necessary to ensure the security of the North Atlantic area.

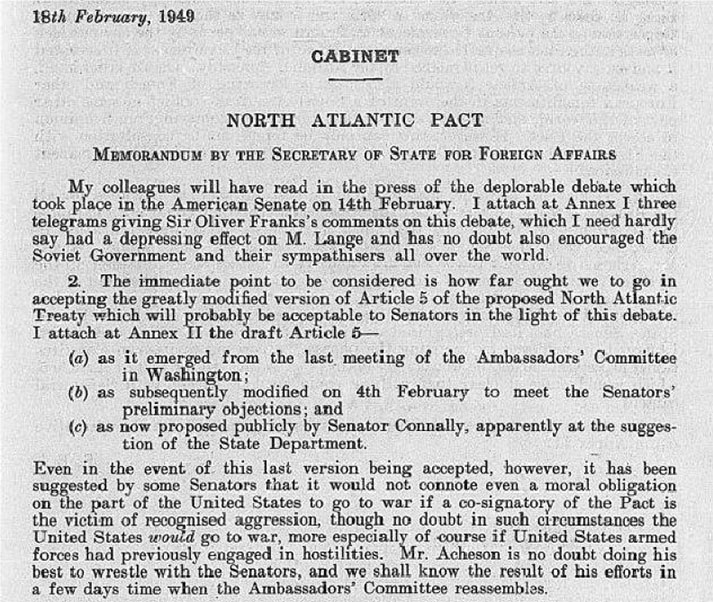

Dean Acheson replaced Marshall as US Secretary of State in January 1949. He soon discovered that only partial agreement had been reached in Congress: several influential senators were expressing concern that, by signing the treaty, the United States would be automatically committing itself to war. Bevin was furious at this further delay. In a memorandum dated 18 February, he informed his Cabinet colleagues that ‘Mr Acheson is no doubt doing his best to wrestle with the senators’ (CAB 129/32/34).

Cabinet Memorandum 18 February 1949. Catalogue reference: CAB 129/32/34

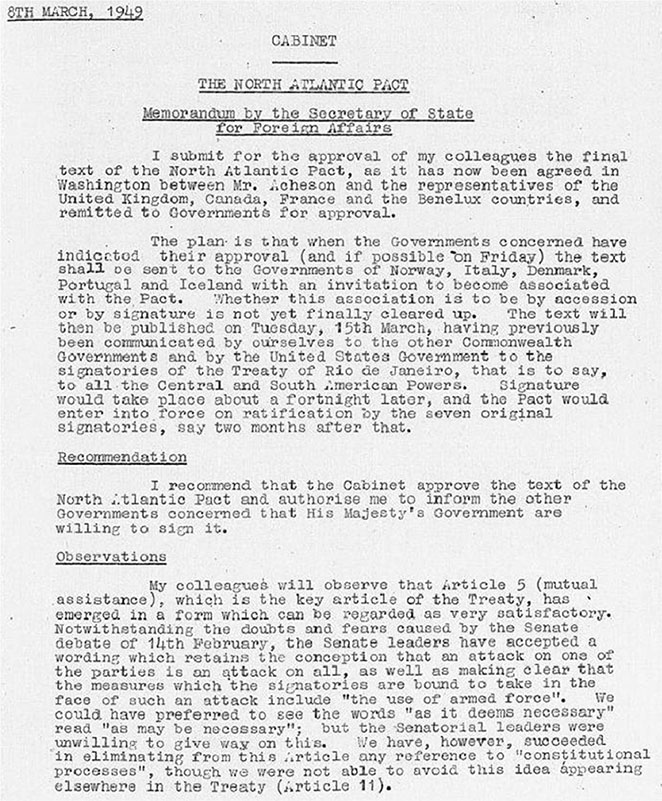

With Truman’s personal intervention, a compromise was reached. To satisfy those senators opposed to the Treaty, it was agreed that the phrase ‘as it deems necessary’ should be included in Article 5, the article relating to mutual assistance. Bevin saw this as the key article of the treaty. Although he would have preferred the phrase ‘as may be necessary’, he described the wording in the final draft as ‘very satisfactory’.

The Senate leaders had accepted a wording that retained the concept that an attack on one member was an attack on all. It also made it clear that the measures signatory states were bound to take in the event of an attack included the use of armed force. Any reference to constitutional processes had been successfully eliminated from Article 5, although it had not been possible to prevent the idea appearing elsewhere in the Treaty.

On the whole, Bevin felt that Britain could be well satisfied with the draft Treaty as it emerged. He concluded that the Pact had teeth and would give strong grounds for encouragement to Europe. On 8 March 1949, Bevin submitted the final draft of the Treaty to Cabinet for approval. He recommended that he should be authorised to ‘inform the other governments concerned that His Majesty’s Government are willing to sign it’ (CAB 129/33/16).

Cabinet Memorandum 8th March 1949. Catalogue reference: CAB 129/33/16

The North Atlantic Treaty was signed by the Foreign Ministers of the 12 signatory states on 4 April 1949. It came into force on 24 August, and a strategic concept for the defence of the Alliance was agreed in October. Bevin had finally achieved his vision of an alliance that linked America to the defence of Western Europe, as well as securing a special relationship with the United States and Canada. When the Treaty provisions were debated in the House of Commons on 12 May, Bevin received praise from both his own side and the opposition. He himself saw it as his greatest achievement, outshining even the creation of the Transport and General Workers’ Union.

Seventy years on, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation that Bevin did so much to bring into being is still in existence – although it has changed and evolved in ways that he could not have foreseen. As he envisaged, NATO is still a major force in maintaining peace and security in, and beyond, the Western World. The signing of the Treaty in 1949 established a close relationship between the United States and Britain and the rest of Europe: it is still as important and valid as it was then.

Bevin’s vision of an effective alliance between America and Western Europe has evolved into an organisation that plays an essential role in the maintenance of peace and security in today’s world.

Further reading

What’s the context? 4 April 1949: signature of the North Atlantic Treaty (History of government blog)

A really interesting piece, thanks

One minor typo however: Denis Healey was Labour’s International Secretary not Britain’s

Dear Simon

We’ve corrected that now – thanks for pointing it out!

Best wishes,

Matthew

Hi Matthew,

I am looking to write my dissertation about Bevin and his influence on either NATO, or European integration more generally (through the Marshall Plan). However, I am struggling to find enough primary source to undertake this – would you be able to point me in the right direction?

Thanks!

There are many primary sources relating to Bevin and his influence on NATO, European integration and the Marshall Plan, both here At The National Archives (some of which I used in my blog) and elsewhere. I suggest that you consult our guides to Cabinet and its committees at https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/cabinet-and-committees/, Parliament at https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/parliament/, and Foreign Office and Foreign and Commonwealth Office correspondence 1920 onwards at https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/foreign-office-and-foreign-and-commonwealth-office-correspondence-1920-onwards/. You could try searching Cabinet papers online at https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/cabinetpapers/. You could also try carrying out advanced searches on our catalogue Discovery at https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ using search terms such as Bevin AND NATO, or Bevin AND Marshall Plan.

I hope that you find the above helpful and wish you every success with your research.

Bevin was the greatest UK Foreign Secretary of the 20th century a maker of the post war world . Amazingly as a person who left school at 12 and was the only literate member of his family.