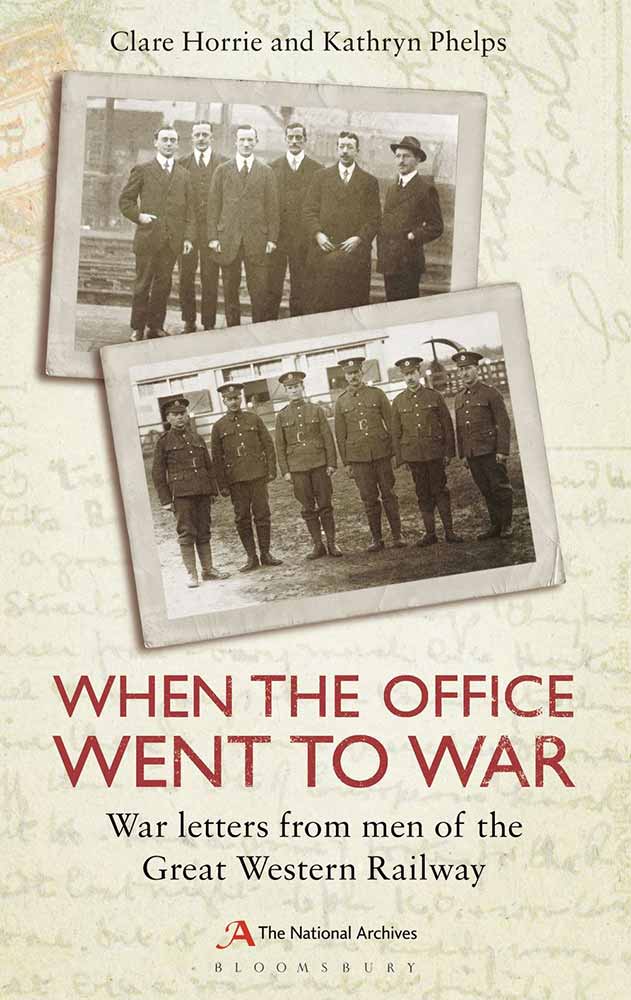

When the Office Went to War book cover

As temperatures drop and preparations for Christmas mount, we cast our thoughts 100 winters back to imagine how a morning in December would have been experienced by a First World War soldier on the front line.

Fortunately our ability to envisage life in the trenches is aided by a series of documents here at The National Archives, just published as When the Office Went to War: a book of letters sent between 1915 and 1918 from employees of Great Western Railway (GWR) to their colleagues back at the office.

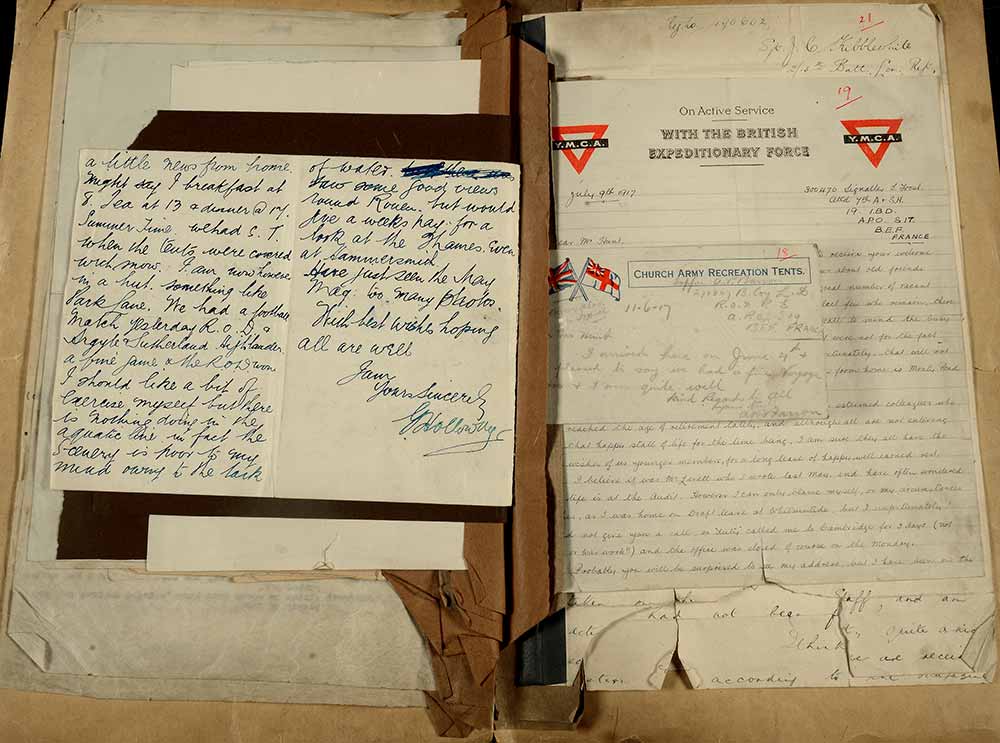

The original documents are arranged into 12 carefully bound scrapbooks (RAIL 253/516) comprising photographs, postcards, newspaper cuttings and letters from those on the front line. Reports back range greatly in topic and tone, including the difficulties of shaving a face studded with shards of shrapnel (‘I had not had a shave for about a week before I was wounded. I look a pretty picture’); enemy observations (‘they were a very measly looking lot and very young and some of them burst into tears when I pointed my bayonet at them’); and jokes about how they would assimilate into civilian life upon their return (‘we’ll be digging a little hole in the garden to live in and stirring up our tea with a bit of stick’).

Jonathan George Symons, writing from a hospital in Taplow on 14 December 1915, displays the sort of cheery disposition common in front line correspondence and throughout these letters:

‘At last I have arrived in England. Left Boulogne Sunday and travelled via Southampton to Taplow. My right foot is still very bad and they told me at Boulogne that I might have to have my big toe amputated. Anyway I hope not. If they do start any of that business I hope they will cut off some of the right side of the foot, for they would do me a favour by ridding me of a beautiful corn that has troubled me for a good many years…’

Hugh Andrew Skilling’s account, written almost two years later on 5 January 1917 from France, takes a more realistic approach. Yet he still manages to slip in a pun:

‘The sights and smells were awful, as a good many of the chaps lay just as they fell during the advance. It was impossible to bury them. Also there were about a dozen dead horses round about in the mud that were killed by shell fire while bringing up ammunition for the guns. Our guns never cease down there, as soon as one section stop, another lot open out so you can tell there is Somme noise.’

Another letter follows shortly on 17 January 1917 from a dry-humoured George Holloway making light of insufficient provisions at Bordon Camp, England:

‘It was comfortable and warm in the depot huts at Longmoor but here sleeping is very cold, the blankets are so poor in fact one of mine I think must have been somebody’s muffler before it got in the army. Another, I fancy is a wire netting sample sent to the wrong store. Last night I tried sleeping in my clothes, overcoat, all except boots, was not warm then.’

The RAIL 253/516 records, at The National Archives as a result of the 1947 Transport Act, give us valuable first person insight into the experiences of a group of men ranging in class and education, alongside an insider view on their relationships with colleagues and bosses.

One of the Audit office newsletters, which were put together by GWR staff in Paddington

We can observe how office talk played a significant part in reminding soldiers of a past normality and a future to return to. Here, Harold Watts diverts from his accounts of conflict at Dardanelles in Turkey, written on 23 November 1915, to contemplate what the Audit office must be like in their absence:

‘I expect you have heaps of ladies there now, lord I haven’t seen a woman since April. What do they look like? I expect they scent out the office, and how careful you all must be not to swear.’

Several accounts forgo humour in favour of humbling, more serious break down of events: William Martin, writing on 10 November 1915, revealed:

‘The Germans gave us a warm time of it in the trench. They shelled us every day and night. This field again was crowded with dead and wounded. Two wounded crawled into my part of the trench, one a Northumberland fusilier, who was wounded at 11 o’clock Sunday morning: it was 3.30 Wednesday afternoon when we rescued him. He was a very brave little chap. The other was a Scots Guardsman; he had a fractured thigh. We were relieved on Wednesday evening at dusk and went into a reserve trench, staying there for a day and a night. Early Friday morning we went into billets for two days. You ought to have seen us coming down the road, up to our necks in white mud, rifles rusting, and some of the boys walking along asleep. One chap on my platoon lost his rifle on the march, so that will tell you how some of us were. Never shall I forget that march. The battalion was reorganised and the casualty list made out. We lost about 300 killed wounded and missing. After a couple of day’s rest, we were for the trenches again, and set off at 10.30 Sunday morning.’

‘When the Office Went to War’ was compiled and written by Clare Horrie and Kathryn Phelps, The National Archives’ education specialists. It contains transcripts of the letters, a glossary of words and phrases frequently used by the soldiers (such as ‘dodging the column’, which means to avoid working or going to fight) and details of what happened to the soldiers after the war, unearthed using census records and documents such as the register of railway clerks. You can buy the book on our online bookshop.

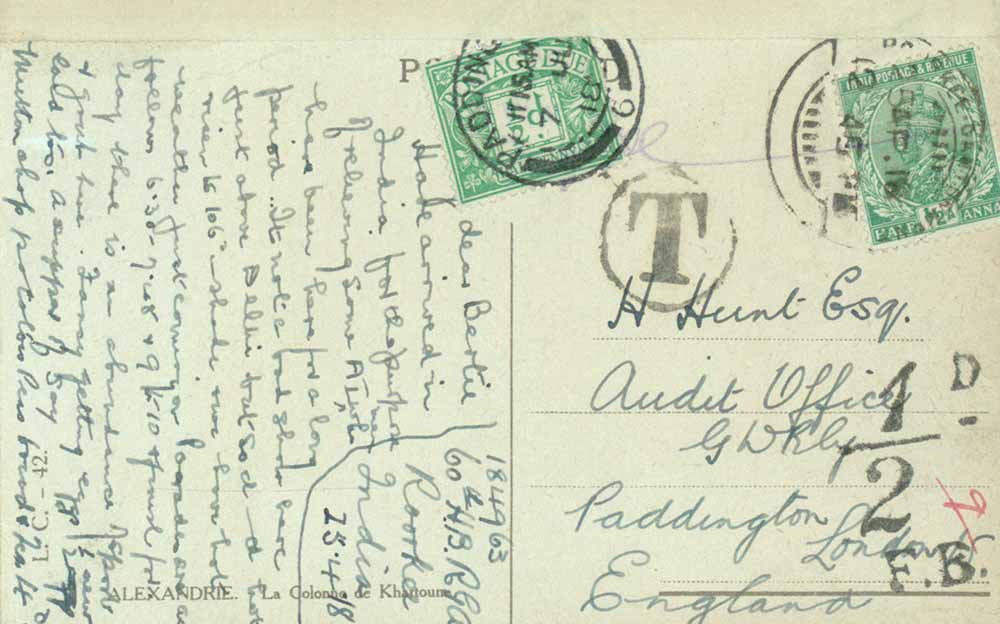

Postcards of Alexandra, Egypt, written by ‘Fatty’ Hyam en route to India, 25 April 1918

[…] As temperatures drop and preparations for Christmas mount, we cast our thoughts 100 winters back to imagine how a morning in December would have been experienced by a First World War… Go to Source […]

Just a small correction: the letters weren’t from employees of “First Great Western Railway” because that company is a 21st-century creation. They worked for the Great Western Railway, a different and far older company, as the cover of the book correctly states.

Hi Mike,

Thanks for your comment. I have updated the blog accordingly.

Best,

Nell