This blog post is part of 20sStreets, in which we explore local history stories in the 1921 Census, connecting people of the 2020s with people of the 1920s. Discover your own local history and enter our 20sStreets competition.

The 1921 Census opens up many possibilities for research. One of the most interesting subjects to look at is occupations and to see how particular occupations dominated different areas. There are various ways to do this, and one is Table XLIV in the General Report. This table covers local information for the occupations of males in England and Wales, by county, and you can work your way through it to determine which industries were significant for particular regions and places.

In the table, some areas have stand-out occupations, whereby they are the only location in which a particular trade or industry is listed as a key area of work. Staffordshire is the only county for which the potteries feature at all. No other county lists it as significant for men (or for women), and Staffordshire lists both potters and brick and pottery kiln workers as key employers. Furnace men also feature highly, along with foundry workers, smiths, machine tool workers and fitters. In Staffordshire, 47 per 1,000 men were makers of bricks, pottery or earthenware, the highest in the country.

The equivalent table for women’s employment in the General Report for the 1921 Census is Table XLIX. This shows that the highest proportion of women working in Staffordshire worked in the potteries, with only metalworking comparing, and over five times as many women worked in potteries in Staffordshire as undertook any other line of work. 79% of all female pottery workers in the 1921 Census were enumerated in Staffordshire; of these, 66% were enumerated in Stoke itself. In England and Wales, 88% of all pottery painters were female, 53% of potters, 50% of dippers and glazers, while only 6% of kiln workers were women (1927 report, p. 122).

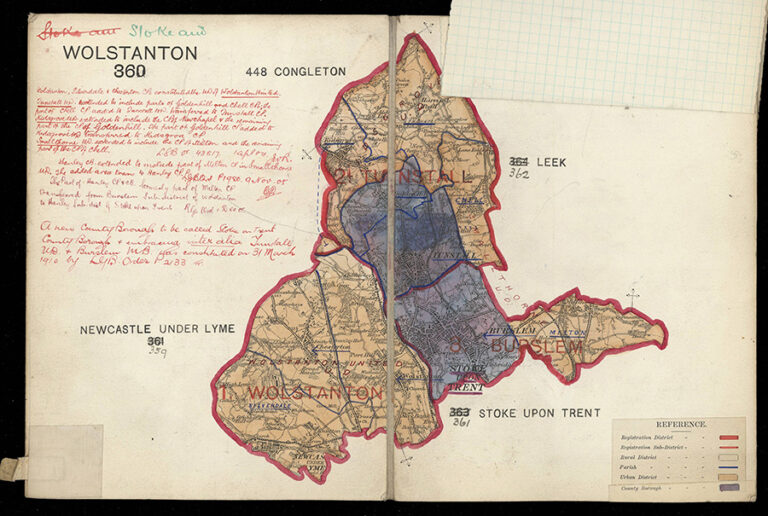

Makers of bricks and pottery in Stoke CB totalled 18,386 persons aged 12 and over, which included the majority of the 1,351 women and 187 men calling themselves ‘pottery painters’ in Staffordshire in the Census. This is around 14% of the entire population of the county. One area where this is really prevalent is Tunstall, where almost every household counts at least one member working in some capacity in one of the many potteries around the city.

The renowned pottery designer, Clarice Cliff, is among those living and working here at this point in time. Clarice’s work really took off in the late 1920s, and her work is instantly recognisable. Examples of her work are held in the Victoria & Albert Museum collections, where you can read more about her work.

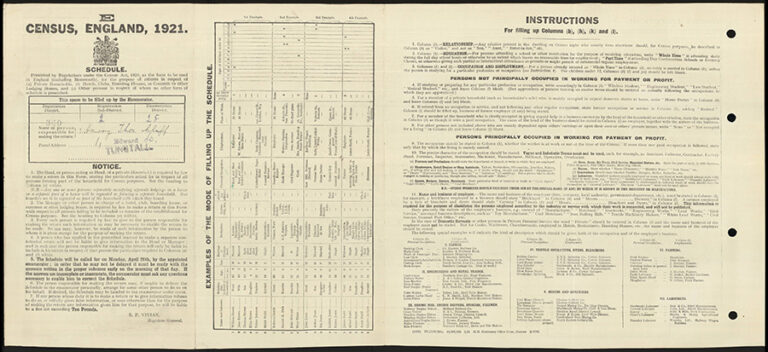

Like many families in Stoke in this period, the potteries were the dominant employer for the Cliff household. Clarice was one of seven children (five daughters, two sons) born to Harry Cliff and Ann Machin. The couple married in 1892, and by 1921 were living at no. 1. Edward Street, Tunstall. Harry was unable to work through ill health and Anne kept house while all their children worked. Their second daughter, Hannah, had married the previous year and moved a few miles away, but the other six children remained at home. Harry, the eldest son, is listed as an out-of-work engineer’s fitter, last employed at the Goldendale Iron Co., where Frank, their younger son, was an apprentice engineer. All four daughters remaining at home are listed as earthenware decorators, and they worked in three different factories. Clarice worked at the Royal Staffordshire, while Sarah Ellen worked at the Alexandra Pottery and both Dorothy and Ethel worked at the Greengates Pottery.

Most of their neighbours on Edward Street were similarly employed. The Broad family at no. 5, for example, comprised three grown-up daughters who were all pottery decorators. Edward, the head of the household, was an ovensman at the Church Bank Pottery, while his daughters worked as pottery decorators at the Unicorn, Gordon and Greenfields potteries. The Heath family at no. 7 also worked in the potteries, at the Brownhills pottery, with Annie, their 21-year-old daughter, listing Wedgewood as her employer. And in one further example, at the Coopers, a multi-generational family living at no. 3, both the working men in the household are listed as working as roofing tile manufacturers at the Boulton Brick & Tile Company.

This street appears to be pretty typical for this part of Staffordshire, and it’s nice to be able to evidence data from the Census Reports with real human stories. If you are interested in pursuing some occupational histories, there are various ways you can do it.

Useful resources

- The General Report for the 1921 Census (www.histpop.org)

- The County Reports for the 1921 Census (www.findmypast.co.uk)

- The Occupational and Employment codes for the 1921 Census (www.findmypast.co.uk)

20sStreets is an exploration of local history stories in the 1921 Census, connecting people of the 2020s with people of the 1920s. Find out more.

Any info on wounded from RNAS …James

Mcquoid…gas victim.1918.

Reference 1921 Trade Codes.

What does 063 code refer to. (06 range not listed in 1921 census trade code index)

Dear Peter,

Thank you for your comment.

To ask questions relating to research, please use our live chat or online form.