On the night of 2 April 1911 census enumerators were collecting the details of households across Britain.

At the same time, in one corner of London, a plain-clothed police office kept a quiet watch on the King’s Road in Chelsea. The house being watched was Onslow Studios.

The officer stayed from 22:00 to 06:00, diligently noting down any movements of people leaving the property. Four males and four females entered, but only three males and two females left.

Why capture such seemingly mundane information? It was believed these individuals were supporters of votes for women.

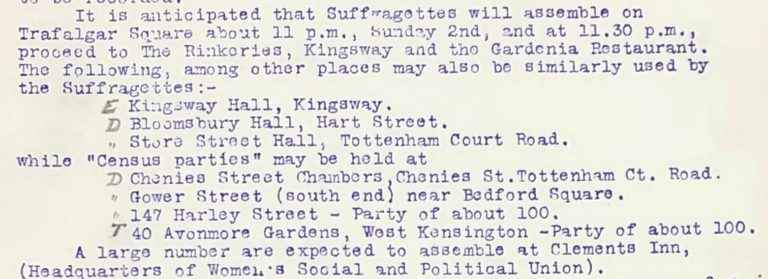

Across London, other women were being observed silently. Superintendents had been told to arrange a ‘reliable and discreet’ police officer to be employed in plain clothes outside a number of places, based on their intelligence gathering from sources such as the Votes for Women newspaper, and their surveillance of militant suffrage organisations[ref]MEPO 2/2023 – Census of 1931: includes papers on possible/probable disruption of the 1911 Census by Suffragettes.[/ref].

The boycott

Votes for women was one of the biggest domestic political issues of the day, and yet the government still refused to give women the franchise. Suffrage supporters across the country remained determined to find yet another way to apply pressure on the government – and this time their means was a mass census boycott. The argument was simple: if they were not treated as citizens with a voice, they would not let themselves be counted on the census.

The Women’s Freedom League (WFL) had instigated the suffrage census protests, mobilising women from a range of suffrage societies to evade. The WFL were one of the most prominent suffrage organisations. They campaigned using the colours white, gold and green and their stance was to generally support militant, but non-violent action[ref]The WFL defined themselves as ‘militant’ but sometimes when pressed would say ‘non-violent militant’. They were distinct from the WSPU, who at times would attack property or politicians.[/ref].

The boycott was also supported by the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and Tax Resistance League, as well as many other organisations and individuals.

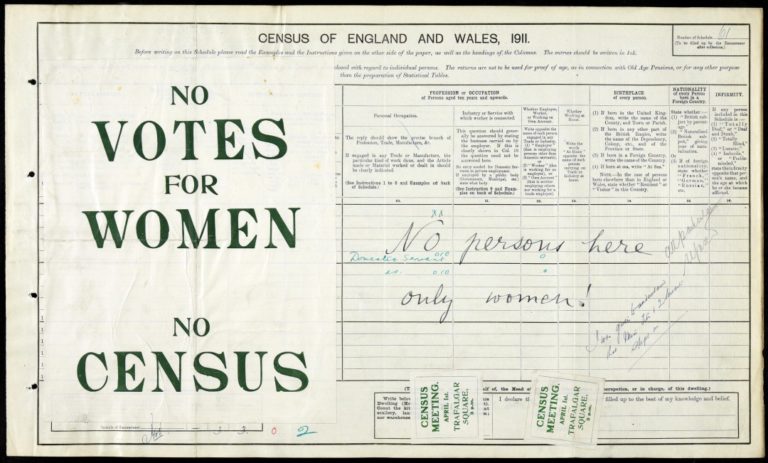

This is the first census where the forms which were completed by the Head of the Household have survived. These schedules provide a unique view on individual acts of protest.

Some suffrage supporters refused to give information, while others made protest statements on the census forms, thereby risking a five pound penalty for no return or a defective return[ref]MEPO 2/2023[/ref]. Sometimes the additional comments by enumerators are also recorded, giving an extra layer of information about the protests and the individuals. In an article in the Daily Mail, the prominent suffragette Annie Kenney noted that if a suffrage Bill was passed, passive resisters would send in their full details, to rectify the missing census information.

In this blog I hope to demonstrate a range of things the 1911 census can shows us about suffrage supporters:

- The census captures famous suffragettes, alongside little-known individuals.

- It represents suffrage supporters from many different societies.

- It shows the suffrage movement was one that spread far and wide across the country, not just affected metropolitan areas.

- And it shows a microcosm of family politics on a single census sheet.

Census parties

On the night of the census many different activities were going on. Some individuals had uprooted from home for the night, while others had actively created big gatherings. In many ways, these different approaches kept police on their toes. Annie Kenney suggested many people would be holding ‘balls, drawing room meetings, and smoking concerts’[ref]Extract from the Daily Mail, 20 March 1911. [/ref].

One of the most significant ‘census parties’ took place in central London and was primarily organised by the WSPU.

While the boycott of the census itself was important, so was the associated publicity and platform it provided the suffrage cause. From 15:00 on 1 April, the day before the census, a mass meeting was held in Trafalgar Square. Police reports detail a crowd slowly gathering, with about 1,000 people in the square by midnight, a mixture of both men and women.

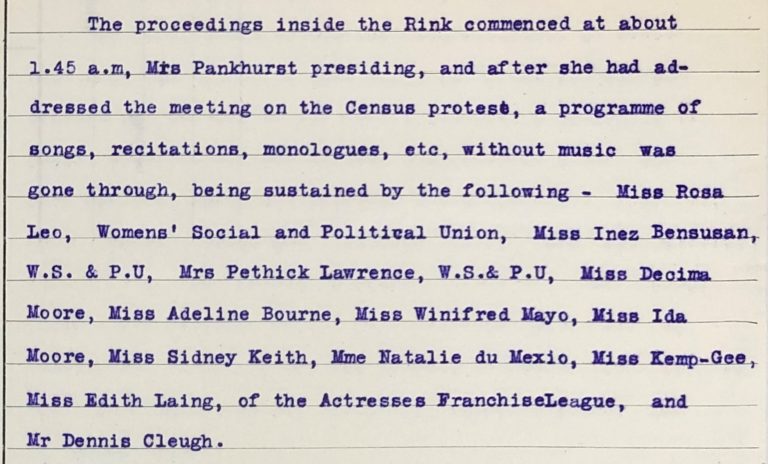

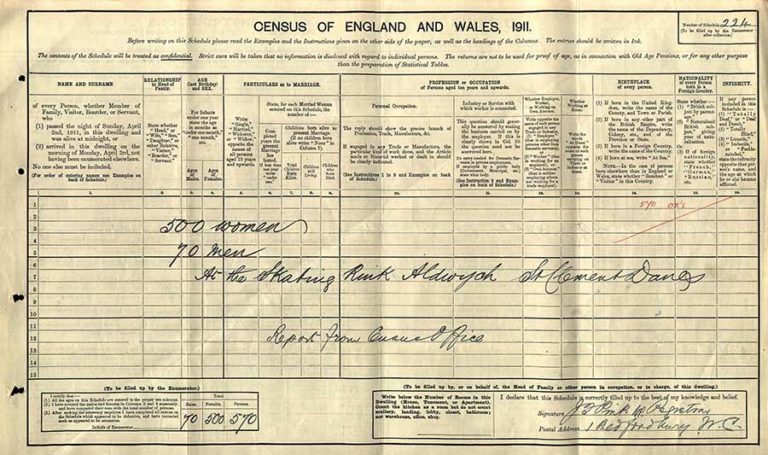

Some of these individuals then headed to Aldwych Skating Rink on the stand, including key leaders in the movement. The skating rink was just around the corner from WSPU headquarters at 4 Clement’s Inn and the WFL headquarters at 1 Robert Street. Census enumerators estimated around 500 women and 70 men were present, although at one point police observed 2,000 people assembled outside the skating rink. Inside the rink, performances were hosted by the Actresses Franchise League. A number of speakers took to the stage, including Christabel Pankhurst, who addressed the meeting on the subject of militancy, saying that she hoped the census protests had shown their promise of more militant action.

A group also relocated to the Gardenia Restaurant in Covent Garden for refreshment. This vegetarian restaurant was regularly frequented by suffragettes.

‘With a view to baffle the enumerators’, suffrage supporters were said to have intentionally travelled constantly between the ice rink and restaurant[ref]MEPO 2/2023[/ref].

Inventive protests

On this same night many other protests were happening across the country.

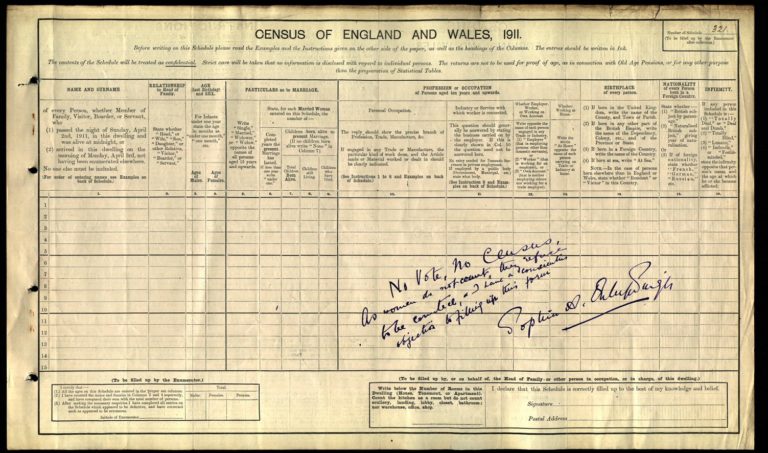

Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, a Maharajah’s daughter, now well-known for her involvement with the Suffragettes, protested in innovative ways, including supporting the Tax Resistance League who claimed ‘taxation without representation is tyranny’.

In 1911 she evaded the census from her grace and favour home in Hampton Court, which was a really bold move. On her census she scrawled:

‘No vote, no census, as women do not count, they refuse to be counted.’

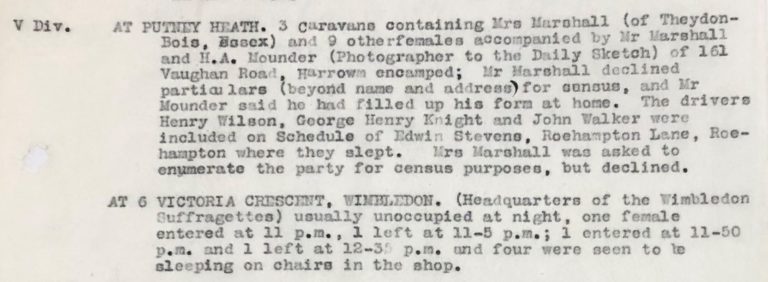

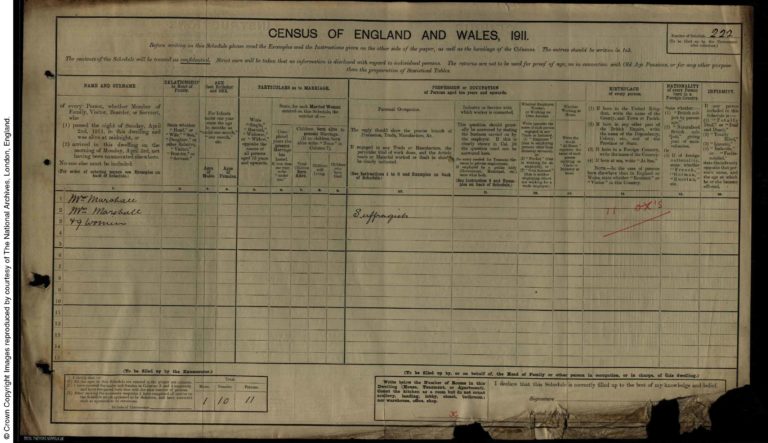

Across London, another police observation was underway, this time in the depths of Putney Heath. The small gathering consisted of ‘Mrs Marshall’ and ‘9 other females’, who each refused to give their details. In typical suffragette style, they had a newspaper photographer with them ready to capture and publicise the moment.

Kitty Marshall, who was actually from Theydon Bois, Essex, was one of Emmeline Pankhurst’s bodyguards and after Pankhurst’s death, helped arrange a statue in her name. In an attempt to physically evade the census enumerators, these women had camped out on the heath in three caravans. Despite the police observations, nothing more than the number of women and Mrs Marshall’s name was recorded.

Two days later on 4 April, the front page of the Daily Sketch showed the motley group of women outside their caravans all holding up ‘No Vote, No Census’ banners[ref]Jill Liddington, Vanishing for the Vote: Suffrage, Citizenship and the Battle for the Census (Manchester, 2014), p. 198.[/ref].

A regional movement

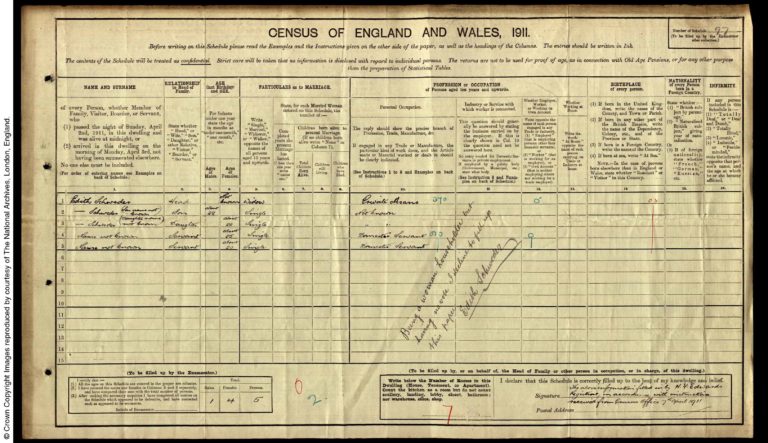

The census was nationwide. While some of our suffrage records are concerned with events in London, the census shows individuals taking action across the country in an attempt to win the vote. Edith Schweder, a widow of private means living in Lamberhurst in Kent, wrote on her census for, the form:

‘Being a woman householder but having no vote I decline to fill up this paper.’

She is one of the individuals we know very little about. The census protests, however, gave her a voice, and we now have her argument for boycotting preserved in her own words.

But not everyone boycotted…

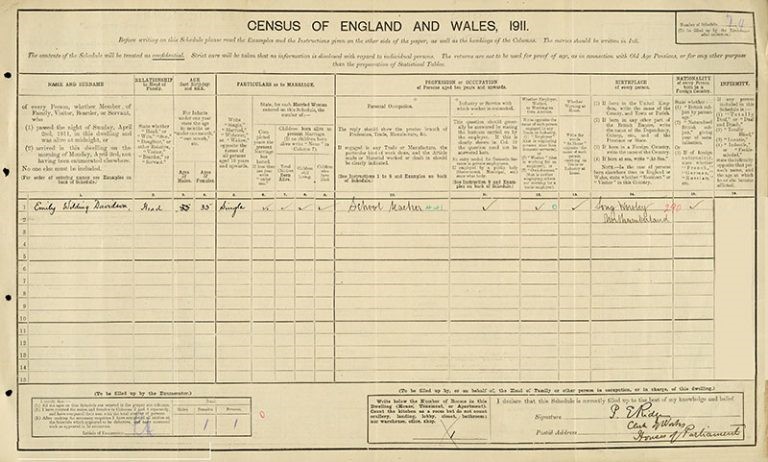

Emily Wilding Davison was an innovative campaigner and activist, but rather than following the conventional form of protest, she chose to make a different type of statement. On census night Emily snuck into the House of Commons in an act of defiance, and she was ultimately recorded as hiding in the crypt of Westminster Hall. In an era where women could not vote or be Members of Parliament, she was making a powerful statement.

Family dynamics

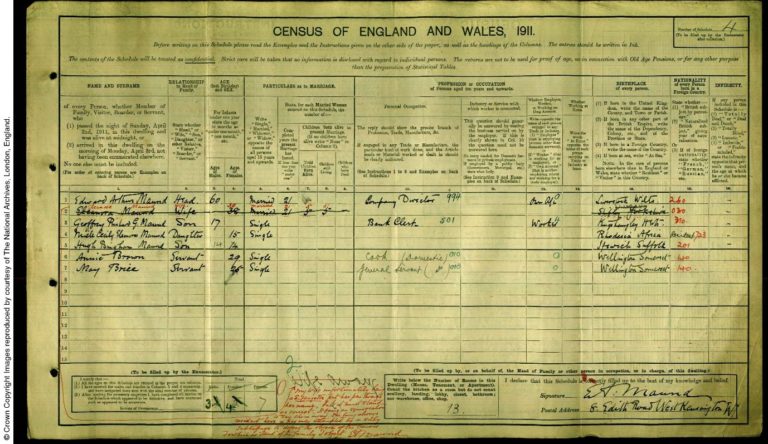

Census schedules can also reveal family dynamics and tensions on census night. Suffrage supporter Eleanora Maund has crossed out the entry written by her husband Edward Arthur Maund, while he added the writing in red:

‘My wife unfortunately being a suffragette put her pen through her name, but it must stand as correct. It being an equivocation to say she is away. She being always resident here and has only attempted by a silly subterfuge to defeat the object of the census to which as ‘Head’ of the family I object.’

Eleanora also shows how the census protests highlight lesser-known suffrage supporters. We don’t know whether Eleanora was associated with a specific suffrage society or just passionate about the cause. But because of the census we know about her belief in women’s suffrage and the tension it caused within her family home.

Resisting the census wasn’t an easy choice for many.

The true scale of the protests will never really be known. But they certainly put another layer of pressure on the government, in demanding votes for women. Despite the threat, none of the women were fined.

On the day after the census, the forms were set to be gathered by enumerators. Police files show even at this point there was a fear that suffrage supporters would disguise themselves and attempt to collect the forms[ref]MEPO 2/2023[/ref]. Ultimately, this is where the protests were a success; once again suffrage supporters had disrupted the normal running of government. Households across the country reminded the government of their belief in votes for women and the lengths they were willing to go to.

If you want to find out more about these protests

- Try searching the census using:

- the names or addresses of known suffrage supporters

- ‘anonymous’ in the name field

- phrases such as ‘no vote no census’ in the keyword field

- wildcard searches in the occupation or keyword field. A search in Ancestry (£) using the wildcard ‘suffrage*’ finds numerous results.

- Listen to the talk Vanishing for the Vote: diverse suffragettes boycott the 1911 census by Jill Liddington on our website.

- Use the wonderful Mapping Women’s Suffrage resource. This project is a work in progress but aims to identify and map the locations of as many Votes for Women campaigners as possible in cities, towns and villages across England in 1911.

- Find the talk No vote no census by Elizabeth Crawford on our website.

It is my understanding that failure to provide details was punishable by a fine. Were the women fined or let-off?.

Fascinating and important history. A marvelous lesson in what close reading of archival sources can tell us. I love the detail about Onslow Studios on the King’s Road; I wish a blue plaque could be put up on that building to publicise its residents’ suffragette history. And brava to Eleanora Maund in Hammersmith!

I knew nothing about the Census Boycott until I came across a census which the female head of household had refused to fill in the details for herself and her daughter, but had added a note to the effect that if she was intelligent enough to fill out the form, she could make an X on a ballot sheet. After posting about this census entry on Facebook, I was directed to this blog, only to find that the unnamed daughter, Rosa Leo, is the first person named (after Emmeline Pankhurst) in the police report above. Unusual details to be able to include in family history research.