The Battle of Cable Street is remembered as a legendary moment in the history of the East End. Powerfully represented in a striking mural, the memory of Cable Street has been physically marked on the capital and the events of 80 years ago will be celebrated this week in events across London.[ref]1. JW3 are running a Cable Street Festival, the HOPE not hate Charitable Trust are launching a new online resource (www.cablestreet.uk), and activities across East London can be explored on the Idea Store site.[/ref]

Cable Street, though, also raises questions about the nature of cultural and collective memory and the role archives and documentary evidence play in maintaining or challenging that memory.

The Cable Street mural, found on St George’s Town Hall

On Sunday 4 October 1936 a march through East London led by Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists (BUF) was disrupted by anti-fascist counter demonstrators. The BUF intended to parade through areas with significant Jewish populations but were halted by a coalition of working men and women, Jewish people, dockers and immigrants. The event has developed an almost mythic status in some circles, representing the East End’s clear rejection of fascism, and is celebrated with a plaque and the mural on walls along Cable Street.

Records at The National Archives, though, show a slightly more nuanced picture. They indicate attempts to ban the fascist demonstration, advice from left wing and Jewish groups encouraging counter-demonstrators to stay away, and a spike in support for the BUF in East London in the immediate aftermath of Cable Street.

The BUF had developed a significant but notorious profile throughout the mid-1930s, even if it had failed to gather any electoral success. Brutal beatings were meted out to protestors at a meeting at Olympia in June 1934, and street attacks on communists and Jewish people increased in regularity and continued through until 1936. The BUF intended to celebrate their summer campaign on 4 October with the march and meetings in Shoreditch, Limehouse, Bow and Bethnal Green. Some of their number, though, had declared it to be a ‘pogrom’ in East London’s Jewish areas.

The upcoming march galvanised action in the local community. In the week leading up to it a deputation of East End mayors applied pressure on the Home Secretary Sir John Simon to ban it, with the Mayor of Stepney claiming that a march ‘…in this large Jewish populated area cannot but be provocative of disturbance and possible riot and danger to persons and property’ (HO 144/21060).

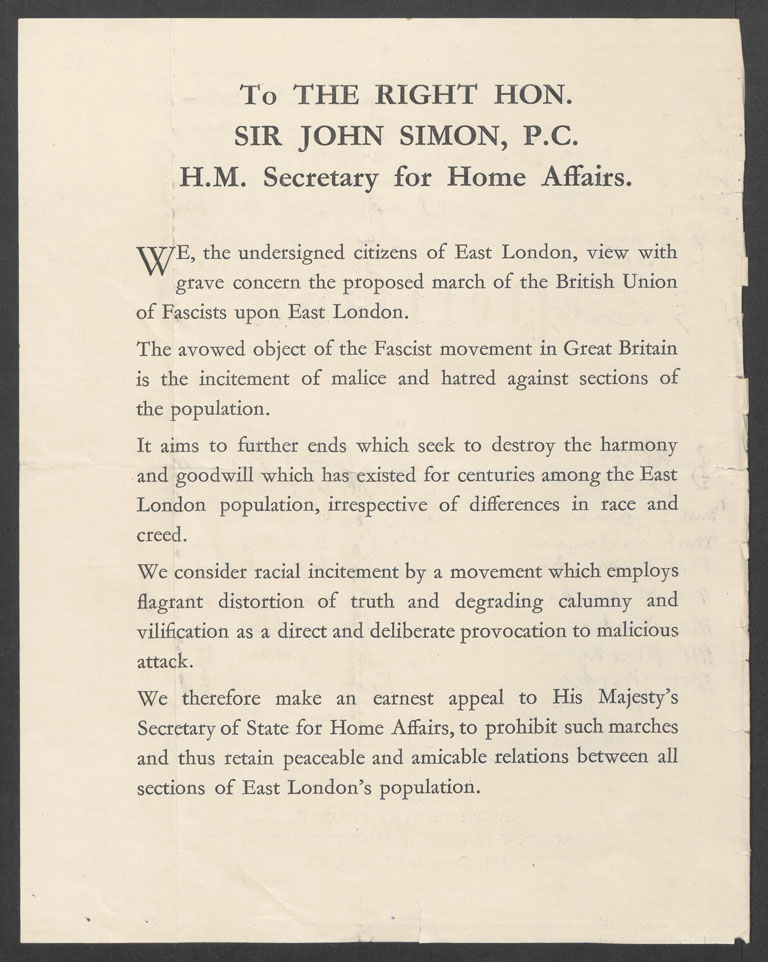

In the two days prior to the march the Jewish People’s Council collected an impressive 100,000 signatures to protest ‘grave concern’. The text of the petition expressed their fear that the ‘avowed object of the Fascist movement in Great Britain is the incitement of malice and hatred against sections of the population’ (HO 144/21060). The petition ultimately asked the Home Secretary to prohibit such marches, for the sake of uniting the community.

Different publications took radically different positions in the days leading up to the march. The Jewish Chronicle issued a warning on the Saturday before the march urging Jewish people to keep away, and going as far as to state ‘Jews who, however innocently, become involved in any possible disorders will be actively helping anti-Semitism and Jew-baiting’ (HO 144/21060).

- Petition to Home Secretary Sir John Simon from Jewish inhabitants of the East End. (HO 144/21060)

- Jewish People’s Council letter appealing for a meeting with Home Secretary Sir John Simon (HO 144/21060)

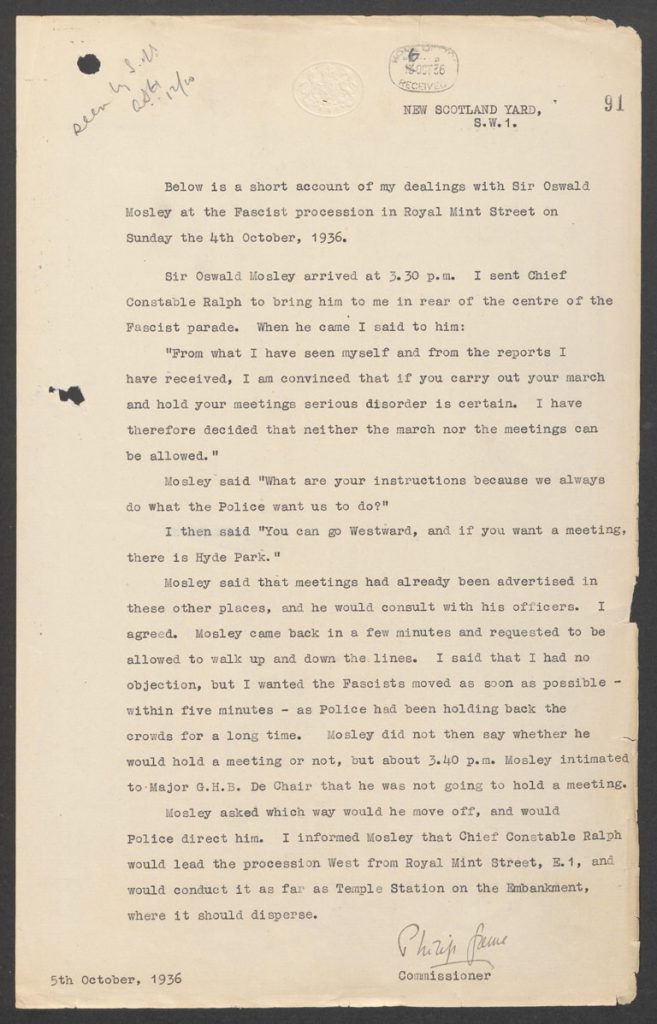

The march went ahead with Sir Phillip Game, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, leading the policing of the event. The initial route was meant to see marchers parade down Commercial Street towards the East End, but a huge crowd of anti-fascist demonstrators blocked the intersection of Whitechapel High Street and Leman Street. The police advised a new route via Cable Street towards Stepney.

Here, though, counter-demonstrators – using the rallying cry ‘¡No pasarán!’ (‘they shall not pass’), borrowed from Spanish Republicans – had overturned a brick-laden truck to create a barricade. Stones and insults were hurled, and Irish immigrant dockers who lived on the street joined in to halt the march. Following conversations between Game and Mosley, the fascists agreed to abandon the planned route and turned westward towards the Embankment.

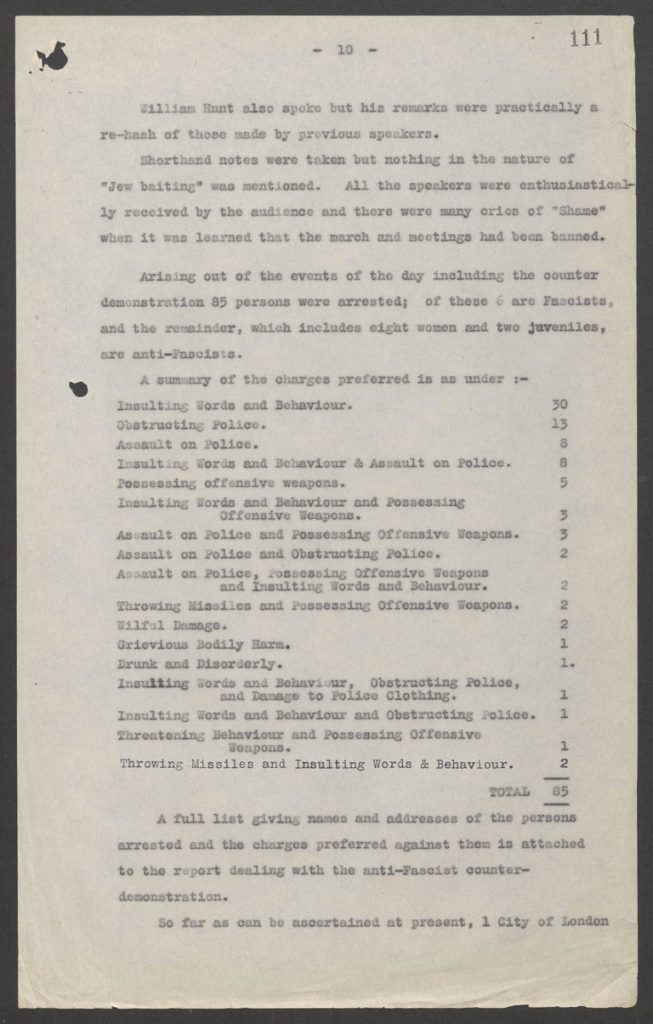

Much of the direct confrontation, though, were not between the marchers and the anti-fascist protestors, but between the counter-demonstrators and the police. Children rolled marbles to fell police horses, and stones and insults were thrown towards police lines, which were trying to keep the two sides separated. This can be seen in an anonymised list of arrests which shows – contrary to the popularised belief – that of 85 people arrested only 6 were fascists. The most common charges were insulting words and behaviour and obstructing police, with very few charged with the more serious charges of grievous bodily harm and wilful damage. Interestingly among the arrests were eight women and two juveniles.

- Sir Phillip Game’s account of the Battle of Cable Street (HO 144/21061)

- Sir Phillip Game’s account of the Battle of Cable Street, including details on arrests (HO 144/21061)

Despite the iconic status of these demonstrations as a triumph over fascism, in the wake of Cable Street the BUF’s membership increased. A confidential report on BUF matters notes that by 27 October membership had increased by a little over 2,000, with these predominately noted in East End branches.

Following the march and the violence of Cable Street, politicians and officials looked at ways to reduce the likelihood of such events being repeated. The Public Order Bill was quickly developed – coming into law at the beginning of January 1937 – and, among other things, banned the use of stewards at open air meetings, ensured that police would have the power to ban marches or alter routes, and outlawed the wearing of political uniforms.

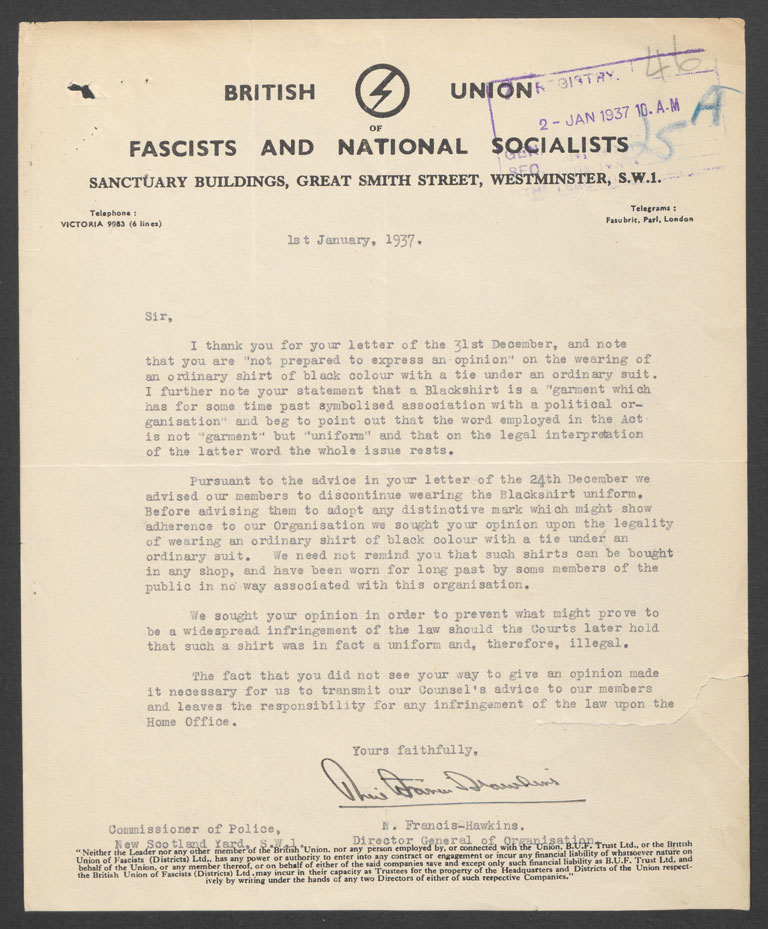

Among the banned uniforms were the black shirts of the British Union of Fascists. The BUF did not dissent from this ruling, reiterating their ‘desire at all times to conform with the law of the land’ (MEPO 3/2153).[ref]2. Similarly, during the disturbances at Cable Street Mosley had said to Sir Phillip Game ‘we always do what the police want us to do’ (HO 144/21061). This fed into left wing concerns that the fascists would influence existing structures of the state, such as the police, to instigate political change.[/ref] However, they argued that the police would not be able to ban the wearing of ‘an ordinary shirt of black colour with a black tie under an ordinary suit’. Meanwhile, the Independent Labour Party were outraged that the red shirts and blouses of their Guild of Youth were being treated in the same way, stating they could not be seen as a military uniform and that they were ‘worn mostly on rambles, for sport purposes, and on weekend outings’ (MEPO 3/2153).

Letter from the British Union of Fascists regarding black shirts (MEPO 3/2513)

The Battle of Cable Street signifies an important point in inter-war British history, when far right political extremism was confronted on the streets of East London and turned away.[ref]3. The history of the mural – which has been vandalised on several occasions and each time repaired – itself eloquently describes Britain’s post-war battles with political extremism and local efforts to maintain community cohesion. The red plaque – installed by Tower Hamlets Environment Trust – can be found on the wall between Cable Street and Dock Street.[/ref] Even if some may claim that the immediate success of the coalition of anti-fascists has been overstated, memories of the event – such as the retelling of stories, commemorative events, and physical memorials – carry their own importance and significance. The documentary evidence in archives allows us to re-engage with historical events and investigate their nuances, but it is local community action and activity that decides how those events are remembered.

There was no march on 4 October 1936 ‘disrupted by anti-fascist counter demonstrators.’ The blackshirts were formed up at Tower Hill and when the police were unable to clear the intended routes through the east end the fascists marched westwards to Temple. Perhaps Demissie and Iglikowski should have noted Sir Phillip Game’s words (at page 10 of his report reproduced above) ‘there were many cries of “Shame” when it was learned that the march and meetings had been banned’.

Bill,

I hope you would agree that we picked our wording carefully for this post – by using the word ‘disrupted’ we did not suggest no march took place, or even that there was a direct confrontation between marchers and counter-demonstrators. However, we can be sure it didn’t go on the originally intended route. I would say that ‘disruption’ describes that quite aptly.

Thanks for reading.

Simon

[…] Battle of Cable Street: 80 Years On S. Demissie & V. Iglikowski, 2016. ‘No Pasarán’: the Battle of Cable Street. The National Archives […]

Not very objective, and people need to seek out the Fascist viewpoint, to get a balanced picture of what really happened that day.