This blog is published as part of Disability History Month (22 November to 22 December 2019).

The image of the shell shocked soldier remains one of the most enduring of the First World War, with service personnel exposed to extreme physical and psychological trauma from which some never recovered. The National Archives’ surviving collection of representative medical records from the First World War (MH 106), containing admission and discharge registers (MH 106/1-2078), medical case sheets (MH 106/2079-2384) and reference volumes (MH 106/2385-2389), detail the causes, outcomes and treatment of servicemen and women from the field ambulances and casualty clearing stations at the front line to the convalescent hospitals in the UK, including the experiences and treatment of those suffering with mental health conditions.

The material in this blog has been drawn from the collection’s medical case sheets, which contain the bulk of the records pertaining to treatments and experiences. The medical case sheets, produced by medics across the chain of evacuation at the front line and on the home front, offer intimate accounts of the circumstances and causes of psychological injuries, details of how patients felt about their illnesses and glimpses into experiences of treatment, making them an excellent source for researching mental illness during the First World War.

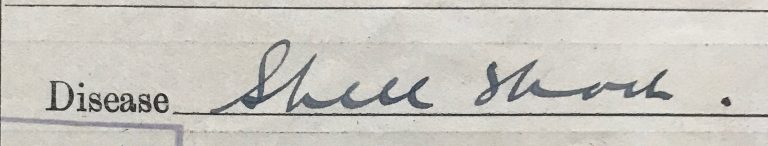

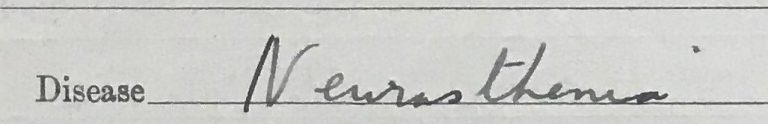

The causes of psychological casualties were wide-ranging, from physical injury and traumatic experiences on the battlefield to the strain of months or years living and fighting in uncomfortable and stressful conditions. Medics remained uncertain of the precise causes of mental health conditions. The diagnoses most commonly given in the records are the pre-war diagnosis ‘neurasthenia’, and ‘shell shock’, first coined in 1915. These terms denoted a range of physical and psychological symptoms, from tremors and muscle spasms, paralysis, recurring nightmares and loss of memory, to depression, anxiety, loss of voice, fits and hallucinations.

Typical shell shock diagnosis given on medical case sheet. Catalogue ref: MH 106/2158/219

Private William James Smith’s diagnosis of neurasthenia given on medical case sheet. Catalogue ref: MH 106/2158/164

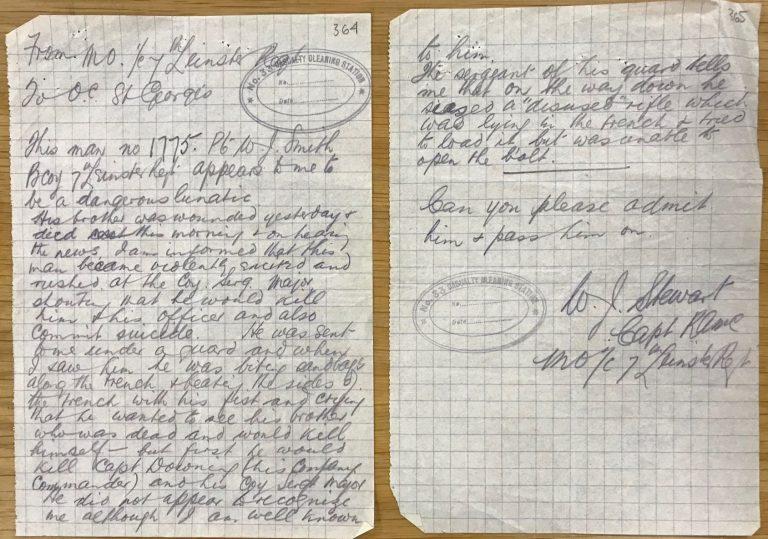

Private William James Smith of the 7th Battalion, Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians), aged 22, was admitted to hospital from the Somme sector in May 1916 having witnessed a grenade explosion that fatally wounded his brother. A vivid eyewitness account by his regimental medical officer Captain W J Stewart states that he was brought to him from the front line under guard ‘biting sandbags along the trench and beating the sides of the trench with his fist and crying out that he wanted to see his brother who was dead’. In his distress Smith attempted to attack his commanding officer and also threatened suicide.

Handwritten report by Captain W J Stewart concerning Private William James Smith, May 1917. Catalogue ref: MH 106/2158/164

Private Smith was evacuated to the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley, where he was diagnosed with neurasthenia. Smith’s records give a pre-war history of mental ill health; he had spent time in an asylum as a child and suffered with ‘a falling sickness’ as a teenager, which was allegedly cured by a priest with a relic. Doctors described his condition as due to ‘the effect of psychic trauma on an unstable mentality’. Smith was declared unfit for further military service and discharged from the Red Cross hospital in Maghull, near Liverpool, in January 1917. While his condition had improved, he remained ‘nervous and excitable’ and had a stutter and finger tremors.

Prior to his hospitalisation Smith had spent seven months on active service in the trenches, serving in Belgium and at Loos prior to the Somme. Considering his pre-war history, we may question whether Smith was ever well enough to have served in the trenches, and whether his experience of extreme trauma and bereavement represents the onset of new symptoms, or the return of old ones.

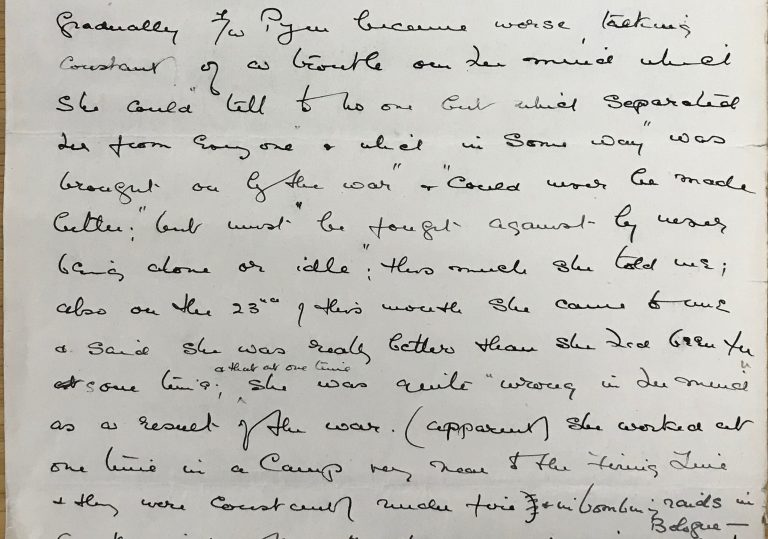

The case of 28-year-old Forewoman (equivalent to Sergeant) Alice M Pym of the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps offers a striking account of her own perceptions of her illness. According to her medical records, Pym had begun ‘very strenuous and responsible’ work supervising camp cookhouses in France in early 1917, working very close to the firing line and experiencing German air raids. In September 1919 she began work as a Senior Quarters Forewoman at the QMAAC camp at Dieppe, where her mental health began to deteriorate. Her records include a report by the Voluntary Aid Detachment Superintendent in charge of the sick bay at Dieppe, E Thompson-Peffe, who reports that Pym became very concerned about her responsibilities and underwent ‘a considerable change in demeanour’, experiencing symptoms of ‘depression of mind’ and ‘forgetfulness and abstraction’.

Thompson-Peffe’s report quotes Pym’s own descriptions of her difficulties, describing how she was ‘talking constantly of a trouble on her mind which she could “tell no one but which separated her from everyone” and which in some way “was brought on by the war” and “could never be made better” but must “be fought against by never being alone or idle”’.

Pym also described herself as ‘“wrong in the mind” as a result of the war’. By the end of November she was admitted to hospital at Dieppe and was reported to have been banging her head against the walls. Before her evacuation to Britain she visited Thompson-Peffe: ‘She asked to see me personally and seemed very depressed, telling me she felt herself not wanted by several girls of whom she was very fond and would I say goodbye to them when she was gone and tell them how she loved them as she herself was bad at expressing her feelings’. Thompson-Peffe reassured her that she ‘knew the three special friends were equally as fond of her, and that they were all anxious she should have everything that could be done for her to make her alright again and that it was for this only that they wanted her to go to hospital’.

Handwritten report by Superintendent E Thompson-Peffe concerning Forewoman Alice M Pym, December 1919. Catalogue ref: MH 106/2208, f.14

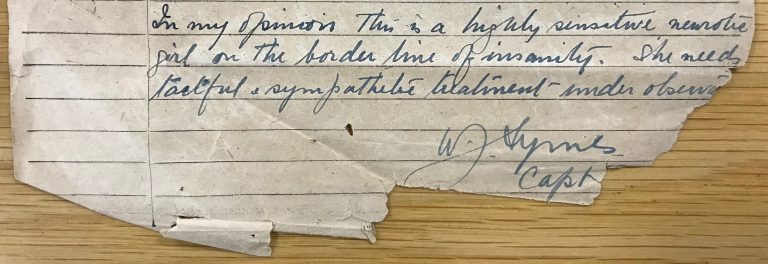

Upon admission to hospital Pym had a range of symptoms including anxiety, paranoia and delusions, but she was not given a comprehensive diagnosis and there is little evidence of treatment. At the QMAAC Hospital at Isleworth, she was described as ‘a very intelligent and well-read girl, and extremely capable in her work’, who had been put under significant strain during the course of her work. Indeed Pym herself believed her condition to have been brought on by the war. Pym’s records give no outcome, but the doctor in charge of her case at the detention hospital at Dieppe described her as ‘a highly sensitive neurotic girl’ and recommends ‘tactful and sympathetic treatment’.

Extract from Forewoman Alice M Pym’s medical case sheets, November 1919. Catalogue ref: MH 106/2208, f.8

The treatment offered to those suffering with mental health conditions was often little more than rest and observation in convalescent hospitals in the countryside. During the course of the war talking and persuasion therapies were developed, and electro-shock therapy was also used.

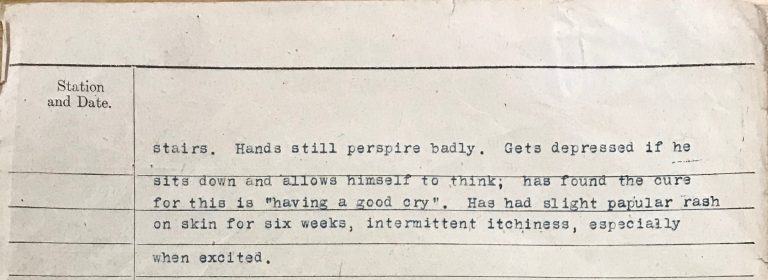

The MH 106 records also show how patients were encouraged to take up hobbies and active pursuits to distract them and provide an alternative focus. Captain H R Lecomber of the Royal Flying Corps was admitted to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh in April 1917 with a diagnosis of neurasthenia, suffering with insomnia, phobias and nightmares. During his course of treatment he busied himself with gardening and swimming. His records also state that he ‘gets depressed if he sits down and allows himself to think; has found the cure for this is “having a good cry”’.

Extract from Captain H R Lecomber’s medical case sheet from Craiglockhart War Hospital, April 1917. Catalogue ref: MH 106/2204, f.267

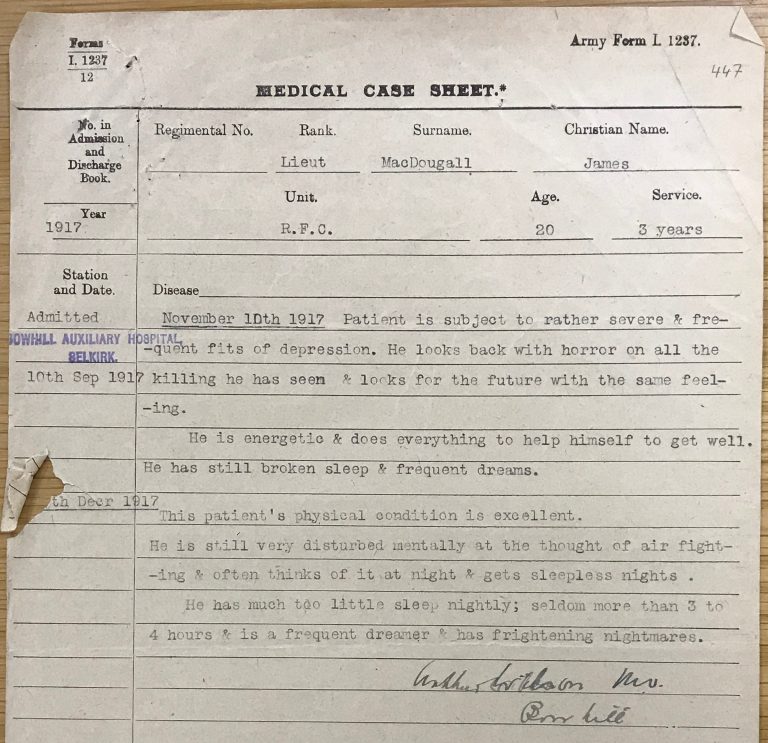

Lieutenant James McDougall was also admitted to Craiglockhart in 1917 suffering with neurasthenia. He fought in France and was gassed at Hill 60 near Ypres in 1915. He joined the Royal Flying Corps in August 1916 and flew in Egypt and France, where he was involved in a number of aircraft accidents. Immediately prior to his hospitalisation ‘he felt as if “he would like to lie down in a corner and die”’. His records give detailed accounts of vivid nightmares, describe ‘rather severe and frequent fits of depression’, and state that ‘he looks back with horror on all the killing he has seen and looks for the future with the same feeling’.

During his treatment Lieutenant McDougall kept busy and was keen to stay active to improve his mental health, taking up fishing in the Rivers Ettrick and Yarrow during treatment at the Bowhill Auxiliary Hospital at Selkirk. No outcome is stated and while McDougall’s mental health improved, the last entry in his records states that he continued to suffer from insomnia and nightmares.

Lieutenant James MacDougall’s [sic] medical case sheet from Bowhill Auxiliary Hospital, Selkirk, September 1917. Catalogue ref: MH 106/2204, f.447

We can gain further insight into their experiences through the PIN 26 representative selection of war disability pension awards, which allow us to see how service personnel were affected by their mental health conditions years and decades after the guns fell silent. In addition, the publication of the 1921 census returns in 2022 will also provide further detail into the conditions of wounded and disabled servicemen and women in the years immediately following the war.

Taken together, these records will shed light on a range of experiences of disabled veterans, and allow us to build a more comprehensive picture of the stories of service personnel affected by mental health conditions as a result of their service in the First World War.

You can currently search over 60 boxes of MH 106 medical case sheets to item level in our catalogue, Discovery. More boxes will become available to search as work to catalogue the series continues. The MH 106 admission and discharge registers are already available to view on FindMyPast.

The Scottish Census returns will actually be released in June 2021, 100 years and one day after the census was taken.

I found this information very eye opening. I have been researching two uncles who served in ww1 in the Dardanelles. One died of enteric fever and is buried in Chatby Cemetery Egypt. The other returned home and was “no longer physically fit for was service” I often wonder what his post war life was like. He married later and died at age 41, no children that I have found.

So please keep these archives coming, I live in Canada and can only access information online. I am anxiuosley awaiting the release of the 1921 census records with the expectation that this will fill in a lot of blanks on my ancestry tree.

Thank you for all your work. Joyce.