Visit our free exhibition, open until Friday 26 October:

Visit our free exhibition, open until Friday 26 October:

Suffragettes vs the State

There are many misconceptions and over-simplifications in the narrative around the movement for women’s suffrage. Here is my personal selection of myths that records in our collections can counter.

Do you disagree with my selection? What other suffrage myths can you think of? Feel free to comment below!

National Society for Women’s Suffrage address to Queen Victoria on her Diamond Jubilee. Mounted on silk; pen and ink illustrations. 1897. Reference: PP 1/349/2.

Myth 1: The women’s suffrage movement began at the beginning of the 20th century

There were multiple early societies fighting for women’s suffrage prior to the 20th century; most prominently, these were from the 1860s after the first official women’s suffrage petition to Parliament.

As these early suffrage societies were constitutional organisations – which used peaceful, non militant methods of protest – The National Archives tends to hold less records about them. Nevertheless, they were a vital part of the campaigns for the vote.

This document is a Diamond Jubilee address gifted to Queen Victoria in 1897. It is signed by Millicent Garrett Fawcett, on behalf of the Combined Committee of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage: a predecessor of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, NUWSS, of which she was later president.

Myth 2: All suffrage ‘militancy’ was violent direct action

While the women’s suffrage movement is often association with the throwing of stones through shop windows or arson, the methods used were much broader that these headline-grabbing actions. Suffrage supporters used many methods to campaign for the vote, starting with constitution methods such as petitions and mass meetings. These methods continued to be important throughout the movement; however, a lack of progress on this issue in government and increasing frustration led to the use of more diverse methods.

Often it is non-violent direct action that gets forgotten about. Imaginative protests such as tax evasion and census boycotts were increasingly employed. For many this was a strong argument: if women were not treated a citizens with a voice, why should they pay taxes or be counted on the census?

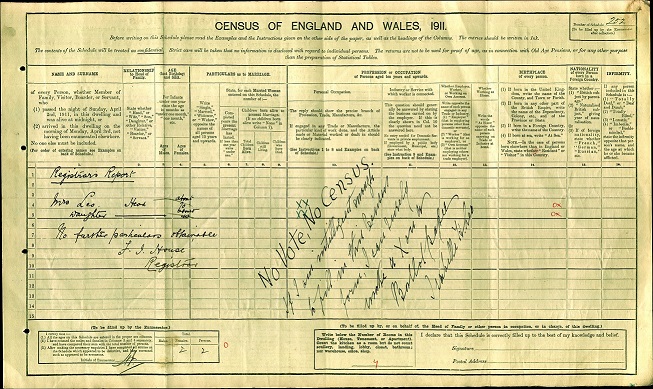

The Women’s Freedom League instigated the suffrage census protests, mobilising women from a range of suffrage societies to boycott the 1911 census. Sometimes this means there is an absence of information on the census – at other times, messages of political protest are left on the census forms.

Census form of Isabella Leo, Paddington, London. Annotated with the words: ‘No vote No Census. If I am intelligent enough to fill in this census form, I am surely intelligent enough to make a X on a ballot paper.’ Reference: RG 14/30.

Myth 3: Suffrage campaigners were only interested in the vote

Traditionally the Pankhursts have been seen as very singularly focused on the vote. However, for most women the vote was a means to an end. It held symbolic importance, but fundamentally it was needed for the electoral power women would gain to influence politics and society as a whole.

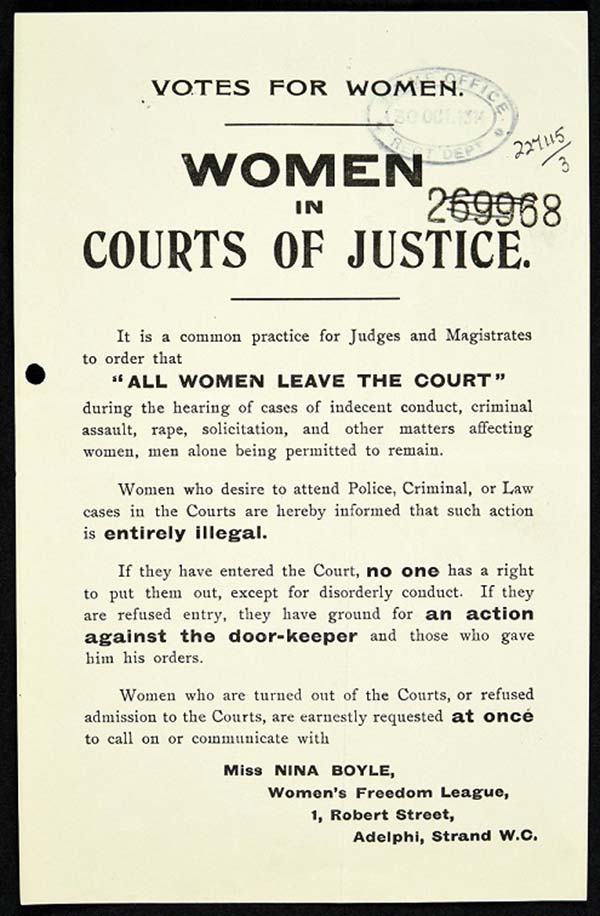

The Women’s Freedom League is an example of a group who lobbied the government on much wider issues. In October 1914 they were campaigning against the exclusion of women during sexual offences trials. They felt it was important for women to be involved in these trials, as it was an issue affecting women’s lives. The objectives of the Women’s Freedom League emphasise their long-terms aims for equality. They described their objects as:

To secure for Women the Parliamentary Vote as it is or may be granted to men; to use the power thus obtained to establish equality of rights and opportunities between the sexes, and to promote the social and industrial well-being of the community.

Many suffrage supporters continued to fight for women’s rights after the vote was initially won.

Flyer on the exclusion of women during sexual offences trials, complaints by Women’s Freedom League 1912-1914. Reference: HO 45/24634.

Headed letter paper stating the aims of the Women’s Freedom League. Reference: HO 45/24634

Myth 4: the movement consisted of middle-class, white, non-disabled women

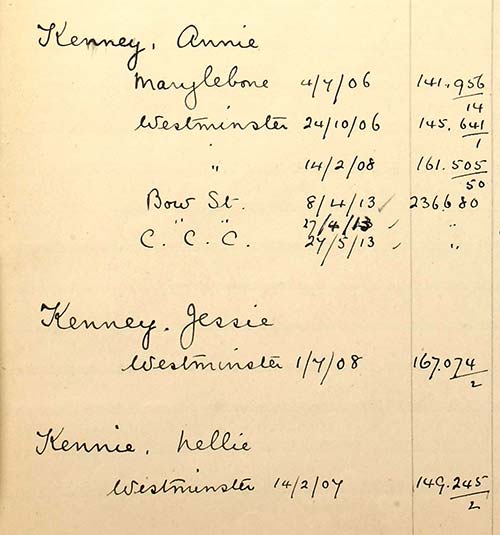

While the suffrage movement is often associated with the middle- or upper-class Mrs Banks-style figure from ‘Mary Poppins’, the reality is far broader. Perhaps most famously, Annie Kenney and her sister Jessie were involved in the WSPU from their early days of militant action. Annie was the only working-class woman to become part of the senior hierarchy of the WSPU.

Annie Kenney, and sisters, as listed in the index of suffragettes arrested between 1906 and 1914. Reference: HO 45/24665. Available to search on Ancestry (£).

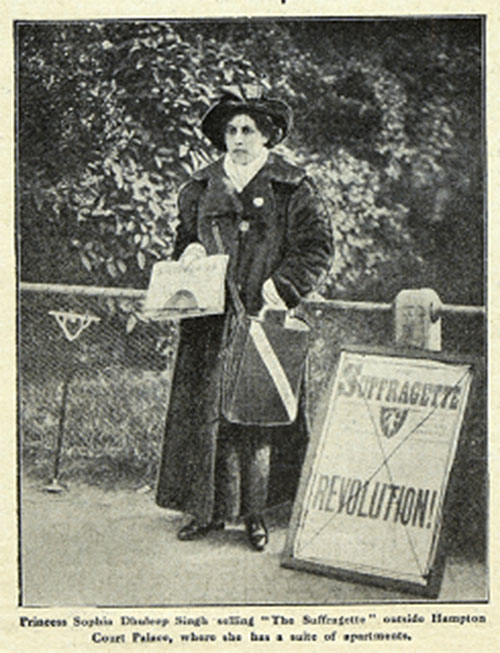

While women of different ethnicities did support the campaigns, their names have not always been recorded in the historical record. Princess Sophia Duleep Singh was better known because of her class status. Sophia was a Maharajah’s daughter, and is now well known for her involvement with the suffrage cause. She sold copies of ‘The Suffragette’ newspaper and was a member of the Tax Resistance League.

In 1911 she evaded the census from her grace and favour home in Hampton Court Palace.

Photograph of Sophia Duleep Singh selling The Suffragette, from the newspaper of the same name, 1913. Reference: ASSI 52/212.

Suffragette Rosa May Billinghurst features in our current exhibition, Suffragettes vs the State. Rosa was disabled from childhood due to paralysis, and spent her adult life campaigning for the vote. Rosa used a hand tricycle, but that didn’t prevent her from engaging in militant activism – including window smashing campaigns and the November 1910 Black Friday protests.

Myth 5: all suffrage supporters were women

When I first started researching the movement for women’s suffrage one of the things that surprised me the most was how many supportive men were actively involved in the campaigns. One particular document is entitled ‘Amnesty of August 1914: index of women arrested 1906-1914’; despite its title, it also includes the names of more than 100 men arrested in the fight for women’s suffrage. As a document about arrests, this only reflects those who campaigned through militant means – there would have been many more men who supported the campaigns in other ways.

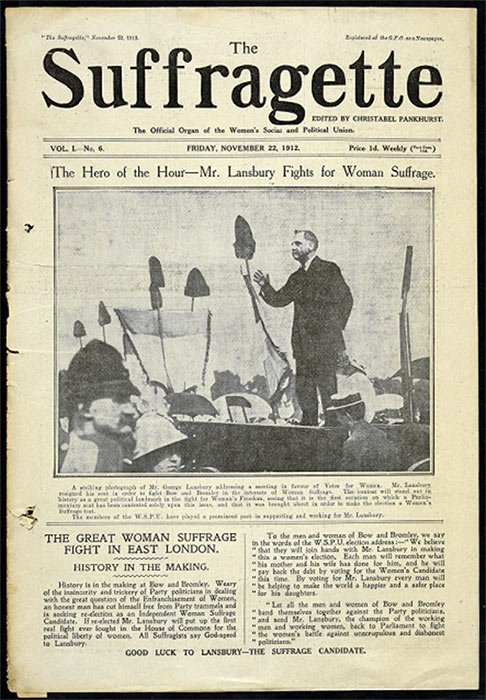

George Lansbury, Labour MP for Bow and Bromley, resigned his seat in 1912 so that he could stand as an independent candidate on the platform of the franchise. The headline on this copy of The Suffrage reads ‘The Hero of The Hour’. Reference: ASSI 52/212.

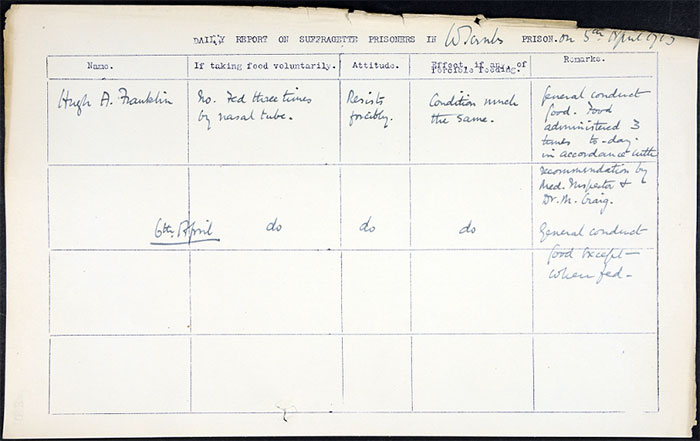

Hugh Arthur Franklin was a prominent male activist. He was arrested five times from 1910 to 1913 and was the first person to be released under the famous Cat and Mouse Act of 1913. This act allowed suffrage prisoners to be released when they went on hunger strike and then re-arrested when they regained health.

Hugh Arthur Franklin, member of the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement: forcibly fed in prison. Reference: HO 144/13025.

Myth 6: there were just two suffrage societies

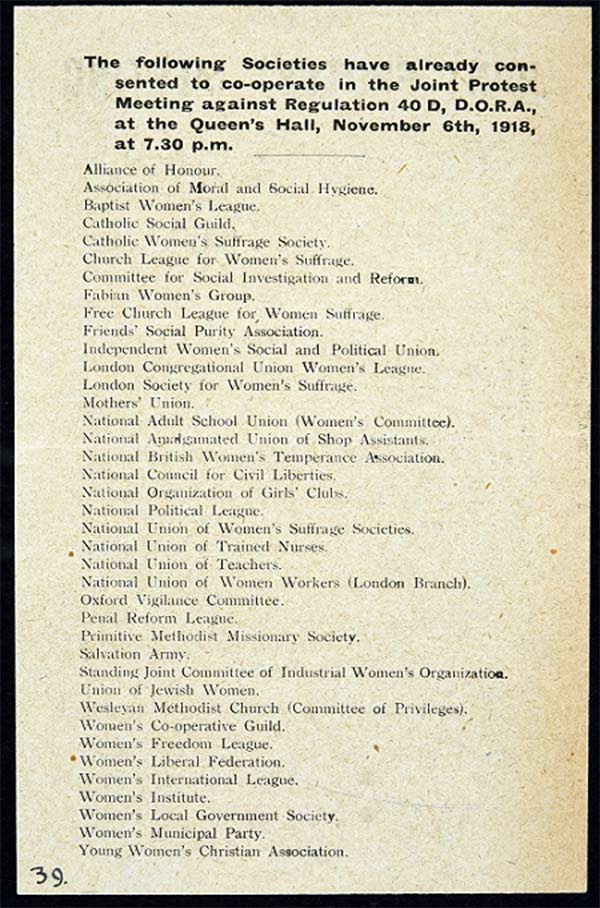

There were two main camps in the suffrage movement: the constitutional (peaceful) campaigners, and those who used more militant methods. However, among these were many smaller societies, often with their own specific angles on the suffrage campaigns – these ranged from tax resistance to religious suffrage societies. These organisations often had their own striking colours and mottos. Societies such as the WSPU, which did not allow male members, often had equivalent male partner organisations. There was also a huge amount of cross membership: suffrage supporters might be an active member of more than one organisation.

- List of many suffrage societies sending delegates to a conference regarding force-feeding. Reference: HO 45/17879.

- Actresses’ Franchise League emblem, from a document on Suffrage disturbances. Catalogue Reference: HO 45/10695/231366.

Myth 7: The movement was London-centric

Hopefully, the Home Office Index and the census have already demonstrated that suffrage action was national. Indeed, Manchester was the original home of the Pankhursts, and where they founded the WSPU. The WSPU had paid regional organisers: while the headquarters were largely London-based, the movement was truly national.

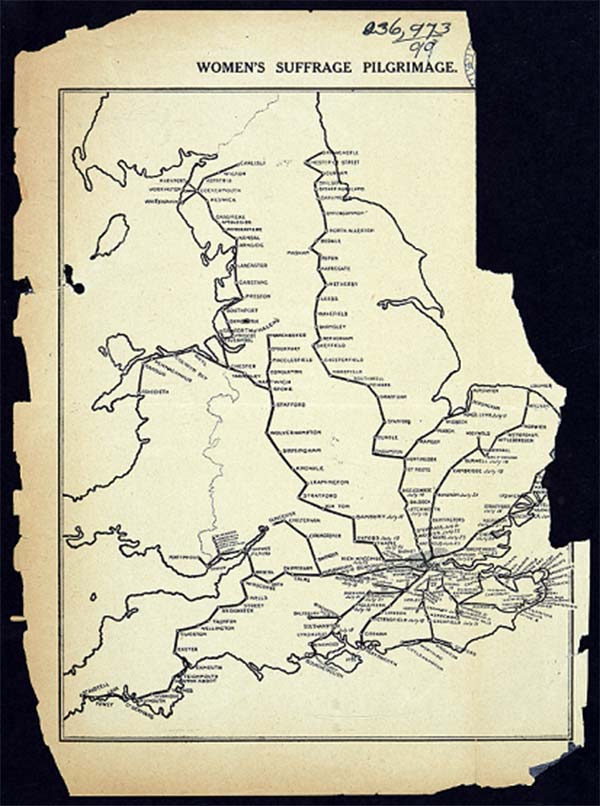

In 1913 the NUWSS set off on a national pilgrimage to reach women all over the country. In one glance, this true demonstrates the scale of the movement. During the following six weeks the suffrage pilgrims held a series of meetings all over Britain, where they sold ‘The Common Cause’ and other NUWSS literature. Reports in Home Office files show that these meetings were not without problems, with comments such as ‘crowds very unruly’. These reports back give a national picture of localised suffrage struggles, from St Austell to Carlisle.

Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage map which shows the extent of the national suffrage campaigns, June to July 1913. Reference: HO45/10695/231366.

Myth 8: suffrage supporters were all hysterical, irrational women

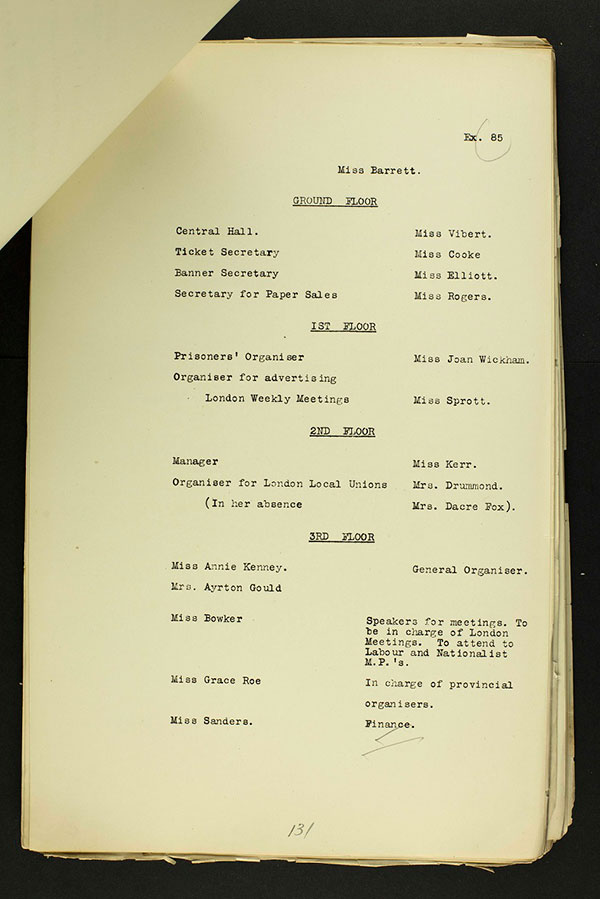

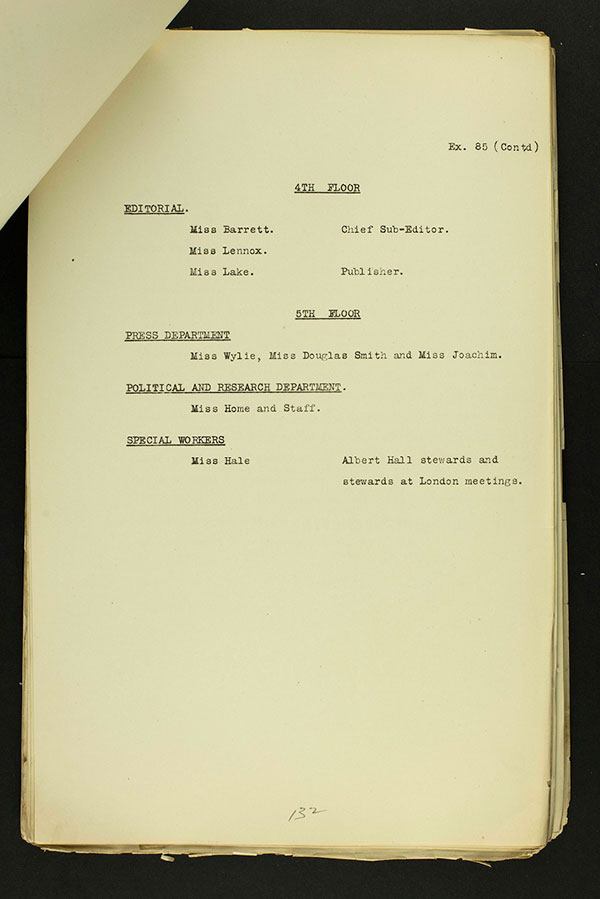

The press often played into the hands of government of the time and depicted Suffragettes as hysterical, irrational women. However, The National Archives’ records show that the suffrage movement was actually highly organised and militant actions were often thoroughly planned.

The offices of the WSPU are a perfect illustration of just how organised the movement was: five floors housed many departments that were vital to the smooth running of such vast and impactful campaign. Staff included a banner secretary, ticket secretary, a prison secretary, and even a press department.

Exhibit 85, listing departments in the WSPU headquarters. Reference: DPP 1/19.

Exhibit 85, listing departments in the WSPU headquarters. Reference: DPP 1/19.

At the height of suffrage militancy in 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst herself asked for the campaigns to be viewed for what they were:

And I want you, not to see these as isolated acts of hysterical women, but to see that it is being carried out on a plan and that it is being carried out with a definite intention and a purpose.

Myth 9: Suffrage campaigning stopped at the outbreak of war

On 4 August 1914, Great Britain declared war on Germany. One of the immediate impacts was the ceasing of militant activism by the WSPU. While the two most prominent suffrage organisations suspended their campaigns at the outbreak of the First World War, other organisations – and, indeed, individuals – did not.

Most notable in our records is the Women’s Freedom League, who continued to campaign and write to the government on issues of importance to them. They worked alongside suffrage organisations such as the Independent WSPU: a breakaway group from the original organisation, who continued to campaign throughout the war.

While significant numbers of women did turn to the war effort, and in many instances joined the services, this was far from the case for all. Sylvia Pankhurst turned to pacifism, extending divisions with the other Pankhurst family members.

Protests by the Women’s Freedom League against the government’s regulation 40D – which controversially enabled the state to imprison a woman for the transmission of venereal disease to a member of the armed forces, 1918. Reference: HO 45/10893/359931.

Myth 10: Women stopped campaigning when the vote was (partially) won

On 6 February 1918, the Representation of the People Act 1918 received Royal Assent, providing some women with a vote in parliamentary elections for the first time. While some suffrage groups disappeared after this moment, and the movement never regained its pre-war rigour, other women’s groups started up.

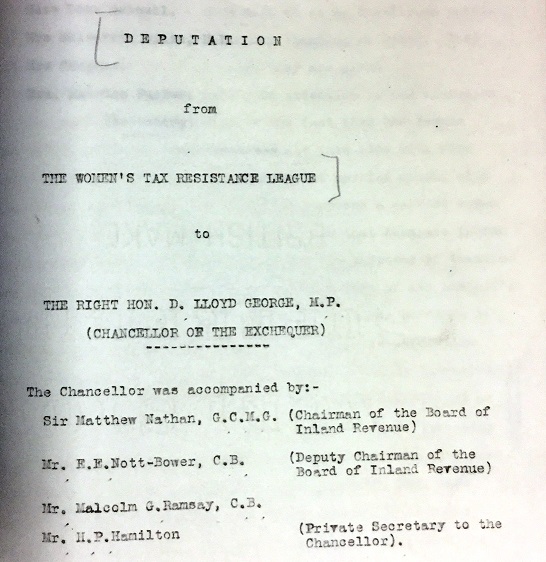

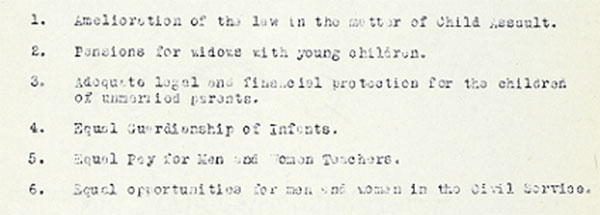

Deputations continued to Parliament demanding the vote on equal terms. Women’s groups, including the Open Door Council and the Six Point Group, also campaigned around wider themes. These included issues such as equal citizenship of infants, equal pay for men and women teachers, and equal opportunities in the civil service. Gaining the vote was only the beginning.

Extract of a letter from the Six Point Group regarding equal opportunities for men and women in the Civil Service, detailing their six organisational aims. Reference: CAB 27/226.

The National Archives Keeper’s Gallery is hosting a suffrage exhibition for 2018: Suffragettes vs. the State explores the militant side of the 20th century women’s suffrage movement. This exhibition will run until Friday 26 October and entry is free.