One of the pleasures of family history is uncovering the facts behind half-remembered stories, discovering the written records that bear out shared memories (or perhaps just as often, give the lie to spurious family legends).

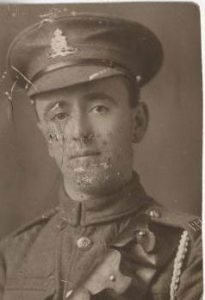

My grandmother, Ermerlinda Beryl Skinner, nee Cooke (known as Bill), was less than three years old when her father, Walter John Cooke, was posted overseas in 1916, and her memories of him before he left were naturally hazy. However, her memory of his return from war was clear, and she spoke of her shock at meeting her father as if for the first time, when she burst into tears, crying “That’s not my daddy!”

In his absence, her mother had talked often of the strong, brave soldier away fighting in the war, and the distress she had felt when a drawn and ill man arrived back at the home she didn’t even remember him living in was still apparent when she spoke of it eight decades later.

I don’t think Bill ever knew much about her father’s war experiences – like so many men returning from the war, he rarely spoke of it, but she knew that he hadn’t been wounded. So when I started researching Walter’s story, I not only wanted to know what the war had been like for him, but also to find out what had caused his sickly appearance that had made such an impression on my grandmother as a young girl.

Walter John Cooke was born in Manchester in 1885 to John Cooke and Elizabeth, nee Enwright, and married Ermerlinda Mary George in Higher Openshaw, Greater Manchester in 1908. By 1913, when my grandmother was born, they were living in Bristol, where Walter worked for The British Engine, Boiler and Electrical Insurance Company. He is described on her birth certificate as an insurance manager.

As I knew that Walter had served as an ordinary soldier (not an officer), I began my research by a search of the First World War Service Records in series WO 363, which are also searchable at Ancestry.co.uk. As regular blog-readers and family history researchers will know, about two thirds of the original records were destroyed by bombing during the Second World War, so I wasn’t hopeful of Walter’s record having survived. However, using a name search of the records, I was pleased to find his record online.

As a married man with a young child, Walter would likely have been reluctant to enlist at the outbreak of war, but I was interested to see from the attestation form in his service record that he had enlisted into the army reserve on 29 November 1915. Recruitment had been high at the start of the war, but had understandably fallen by late 1915, and Walter was one of the last of the ‘Kitchener recruits’ who enlisted voluntarily, prior to the introduction of conscription early the following year. [ref] 1. This was introduced in January 1916 for single men aged 18-41, and extended to married men in June of the same year. It was possible to appeal against conscription by application to a military tribunal – for more information on the tribunal records held at The National Archives, see www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/conscriptionappeals. [/ref]

His record shows that on 29 May 1916, Walter was appointed as a Driver within the 1st South Midland Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, and in October embarked a ship bound for Salonika, where he was posted to the Pack Transport section. So for the first time, I knew the theatre of war in which Walter had seen service – but I knew very little about the Salonika front. [ref] 2. Also known as the Macedonian front. [/ref]

My image of the First World War, formed from school history lessons, documentaries and poetry, focused almost exclusively on the Western Front and the horrors of the trenches in France and Belgium, and I admit I was a little hazy on where Salonika actually was.

I turned to the excellent Long, Long Trail First World War history website to find out more about the campaign. Salonika, now known as Thessaloniki, is now the second largest city in Greece. In 1915, British and French forces landed there at the request of the Greek government to defend against Bulgarian invasion, and although unsuccessful in this immediate aim, remained there until 1918. The Long, Long Trail website provides a more detailed summary of the campaign, which put Walter’s service in context for me.

Returning to the service record, I saw that in December 1916, Walter had joined the ’78 SAAC’, part of the 26th Division. I’m no expert on military abbreviations, so this meant nothing to me – but the Divisional history of the 26th Division on the Long, Long Trail provided the answer: the 78th SAA (Small Arms Ammunition) Section Ammunition Column was part of the 78th Brigade, which in turn formed part of the 26th Division. David Gillespie’s post in the My Tommy’s War series discusses the role of drivers, men who moved field equipment and supplies, so I knew a little about Walter’s rank already. I turned to Alan Wakefield and Simon Moody’s book ‘Under the Devil’s Eye: Britain’s Forgotten Army at Salonika, 1915-1918’ for more information.

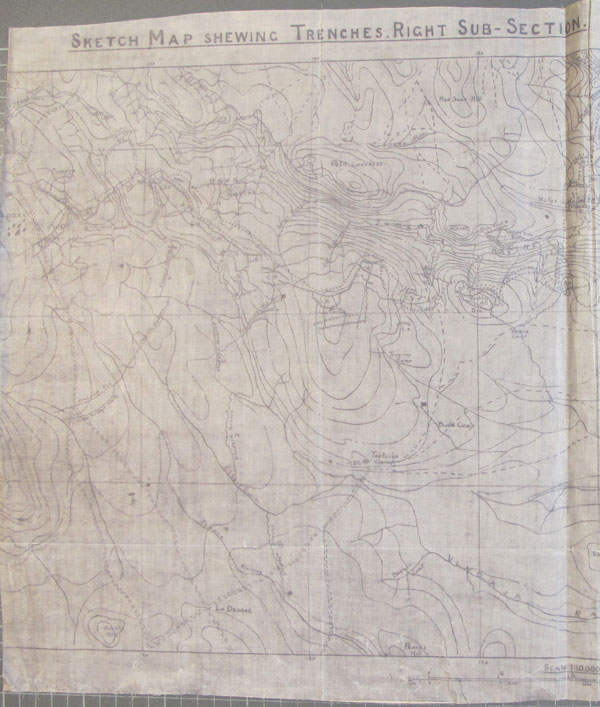

Equipment was mostly moved by horse on the Western Front but, in Salonika, the mountainous terrain meant that the use of horses and wagons was often impossible, so supplies were usually carried in smaller consignments on pack animals like mules, requiring the formation of additional SAA sections to carry ammunition; in Walter’s case, his column supplied the battalions of the 78th Infantry Brigade fighting in the mountains.

I was forming a picture of Walter’s war, leading his mule from the divisional HQ camp and stores up to the frontlines in the mountains. His service record shows that in June 1917 he was appointed acting Lance Bombardier, and in July Acting Bombardier within the 78 SAAC,[ref] 3. Artillery ranks equivalent to Lance Corporal and Corporal. [/ref] so I wondered if he’d been responsible for operational decisions, perhaps choosing between a longer, slower route up the mountains and a shorter but more exposed one which could replenish ammunition supplies more quickly.

I wanted to find out more about the fighting in the region and what it had been like for the men stationed there, so I searched the catalogue listings for two key series, WO 153 – Maps and Plans of the First World War and WO 95 – War Diaries, using search terms like ‘Salonika’ and ’78 Brigade’. The trench maps and panoramas[ref] 4. Including photographs in WO 153/1345 [/ref] show clearly the mountainous terrain in which the fighting took place, and although there are no war diaries specifically for the 78 SAA, there are several divisional diaries for the 26th Division, and several for 78th Infantry Brigade.

It is unusual for individuals to be mentioned by name in the war diaries, but like the maps and plans, they help give an idea of the conditions and military action in Salonika.

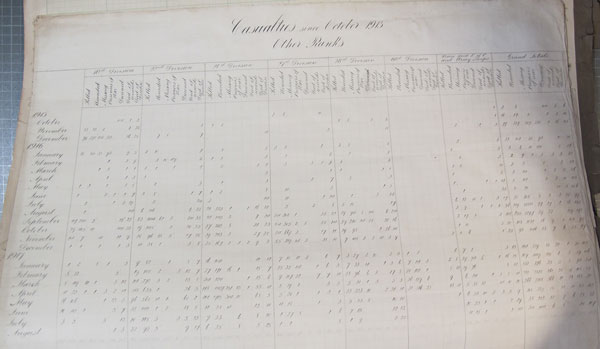

But perhaps the most revealing record I found amongst the plan series was in WO 153/1344, Charts and graphs of British strengths and casualties, which included a statistical table of casualties during the Salonika campaign. For many of the months recorded, and for every division, the number recorded as ‘Died of disease’ exceeds the number ‘Killed’, and often even the number ‘Wounded’. So here was an indication that perhaps it was not gas or shrapnel wounds that had so weakened Walter, but sickness.

According to Wakefield and Moody, the nature of the terrain, full of stagnant pools and blisteringly hot in the summer, meant that the area was one of the worst in Europe for malaria, with many men suffering repeated bouts. The climate and poor sanitary arrangements made dysentery and various enteric diseases almost endemic amongst the troops in the summer months – although in the winter conditions were so cold that, as one officer reported in his diary, “Our overcoats are frozen hard…men can hardly hold their rifles as their hands freeze to the cold metal.”[ref] 5. Quoted in Wakefield and Moody, ‘Under the Devil’s Eye’, p.17 [/ref] Men were given daily doses of quinine, and in July 1917 a specialised enteric hospital was opened in the south-east of the region.

The editor of the newspaper produced for British forces in the region, the Balkan News, wrote that:

“By the summer of…[1918] the Salonica Army was full of listless, anaemic, unhappy, sallow men whose lives were a physical burden to them and a material burden to the Army; who circulated backwards and forwards between hospital and convalescent camps, passing only an occasional few days at work with their units.”[ref] 6. Ibid., p.182 [/ref]

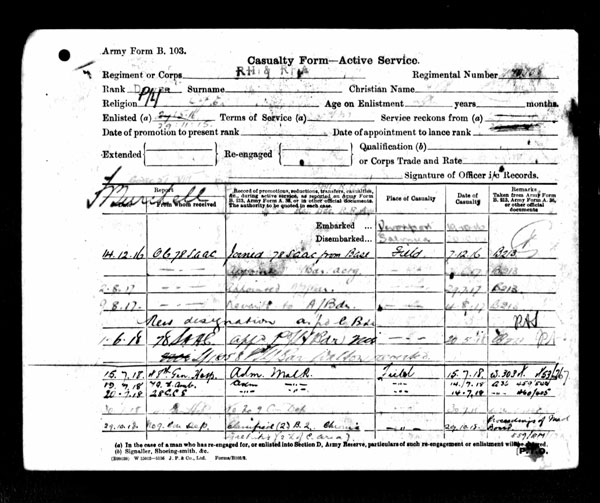

Walter’s service record confirms that he suffered both a bout of malaria and enteric illness. He seems to have remained in relatively good health for over a year, but in July 1918, he was admitted to the 48th General Hospital with malaria, and subsequently moved to the 79th Field Ambulance. In October, he was treated for chronic gastritis, and the following month transferred again to 48th General Hospital.[ref] 7. War diaries of the 48th General Hospital are in WO 95/4934. There are also admission and discharge registers for a number of hospitals and field ambulance units which treated officers and other ranks from Salonika in MH 106 – you can search the series by the number of the hospital or unit. [/ref]The medical papers in his service record note that he was diagnosed with a gastric ulcer, attributed to “service during the present war”.

Three days after his admission to hospital, Walter’s unit, the 78 SAA, was involved the Third Battle of Dojran, where the British forces suffered heavy losses, so I can’t help but feel grateful that his illness took him away from the dangers of the frontline. He saw out the end of the war in the 48th General Hospital, and at New Year was transferred by the hospital ship ‘Magdalena’ to the Military Hospital at Whalley in Lancashire where he completed his convalescence before being demobbed in February 1919. [ref] 8. The campaign medal Walter received are recorded in an index card is at WO 372/5/113, and the medal roll which it relates to is WO 329/152. [/ref]

Casualty form from Walter's service record in series WO 363, showing his admission for malaria and later for chronic gastritis (gastric ulcer)

So this was why Walter had seemed so at odds with Bill’s image of her father when he returned home to Bristol – having spent the much of the last six months in hospital, not due to wounds but, like so many of his compatriots in Salonika, brought low by disease. But Walter was of course one of the lucky ones who made it home, and Bill soon got used to having her father back.

He went back to work with the same company, where he remained until his retirement. The family moved back up to Manchester when my grandmother was 13 – she intimated later that Walter was involved in some kind of misdemeanour at work, which resulted in his being transferred away from Bristol. The surviving records of The British Engine, Boiler and Electrical Insurance Company, including some staff records, are held at Manchester Archives. [ref] 9. You can find the collection listed in Manchester Archives’ online catalogue with collection reference GB124.B.BEI. [/ref] I haven’t yet visited to see if I can find out more, so for the meantime, it remains another of those family stories waiting for the facts to be uncovered….

Kate,

I’m pretty sure your man enlisted under the terms of the Derby Scheme (see http://www.1914-1918.net/derbyscheme.html). This was still voluntary, but the government made it clear that conscription was on it’s way. He was a class B man – he attested and joined the army reserve (as you say), one of the forms in his record shows that he was called up for active service on 26 April, he then trained with a Reserve Brigade prior to his posting to the South Midland Brigade. The front page of his record shows that he actually wanted to join the Army Service Corps (he would probably have still been a driver in the that case), but while the Derby Scheme allowed men to express a preference for a unit, it was not absolutely guaranteed (and this went entirely out of the wnidow under conscription).

Also, while lance bombardier and bombardier are now equivalent to lance corporal and corporal, it was slightly more complicated during the First World War. The artillery also had corporals at that time, who like corporals in other corps wore two stripes, bombardiers wore only one, but unlike lance corporal in other corps it was a substantive rank, rather than an appointment (largely this meant you could only be reduced in rank by judicial action, rather than by adminstrative decision of the CO). Lance bombardiers and acting bombardiers also wore the single stripe, but it was more akin to the position of lance corporal in other units. Following the war the army rationalised all this and lance bombardier and bombardier became equivalent to lance corporal and corporal as you say (the rank of second corporal used by the Royal Engineers and Royal Army Ordnance Corps vanished at the same time).

David

Interesting stuff! I had a great uncle serving in the same area – never researched the details, but my Dad has a letter he sent back to his sisters labelled ‘flowers from Salonika’, which is such a romantic phrase it’s stuck with him. The reality sounds pretty awful, though – and the fact my great uncle was writing from hospital where he was ill not wounded is very much in line with what you’ve outlined here.

Thank you both for your comments and thank you for your helpful advice David. Melinda, it’s interesting how evocative soldiers’ letters can be – but although the family collections include large numbers from from my grandfather and great uncle in the Second World War, which are both fascinating and heartbreaking, sadly none of Walter’s letters survive. I’m sure they would add so much more to the few details we have.

[…] sufferings of a typical Tommy in Salonika are vividly described in this account of Walter John Cooke’s […]

[…] up to fight until late 1915. (Kate has written a fascinating blog post about his war service at http://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/my-tommys-war-mules-and-malaria/#more-10431). He survived the war, but by the time he returned to my mother and grandmother, he was in very […]

[…] My Tommy’s War: Mules and malaria […]

[…] in combat. The sufferings of a typical Tommy in Salonika are vividly described in this account of Walter John Cooke’s war – “My Tommy’s War: Mules and […]