I am currently an undergraduate student at the University of Oxford, studying for a degree in Classics. I’m interested in the Arts and Heritage sector, so a six-week student placement at The National Archives was an exciting opportunity to experience first-hand the work that goes on behind-the-scenes of a national archive.

My placement was centred around the War Office (WO) records, an extensive collection ranging from service records and general office records to hand-drawn maps and private office papers, such as those of Lord Kitchener as Security of State for War between 1914 to 1916.

As a result of the unprecedented circumstances caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, my student placement took place remotely. Yet despite these unusual conditions – working online from home – I still felt like part of the team at The National Archives and received a warm welcome from everyone I met during the six weeks.

This was the first time The National Archives had run a student placement remotely, so mine was truly a unique experience. Each day began with a friendly morning team meeting, which helped to give structure and lay out a timetable for the day.

During the six weeks I was lucky enough to meet with a number of inspirational individuals to discuss their differing roles and the exciting work they do there, including historical, digital and archive research, academic engagement and conservation. Alongside this, I also attended research seminars, forums and met with a current PhD student to discuss her research and life as a collaborative PhD student with both The National Archives and University College London (UCL).

The structure of my student placement followed the steps involved in the process of digitising the archive’s physical documents as part of the archive’s growing digital catalogue. This proved to be a detailed and complex process but also a hugely rewarding and interesting one.

In the first two weeks I got to work with military records, supervised by Will Butler (The National Archives’ Head of Military Records). This work focused on two particular sets of records: Returns of British Army Officers covering 1790s-1830s (WO 25) and British Army Officers, service 1853-1913 (WO 76).

I began by transcribing a selection of records, finding out what information could be extracted from them, and how such information could go on to inform historical research. I then entered the transcription data recorded into a spreadsheet ready for the next stage of the cataloguing process. By analysing this data I was then able to produce statistical averages and percentages concerning the correlations between different factors, such as place of birth, age at enlistment, and number of years in service. This analysis highlighted a number of intriguing relationships found within the military records, such as the percentage of British Army officers born in Ireland during the 18th and 19th centuries.

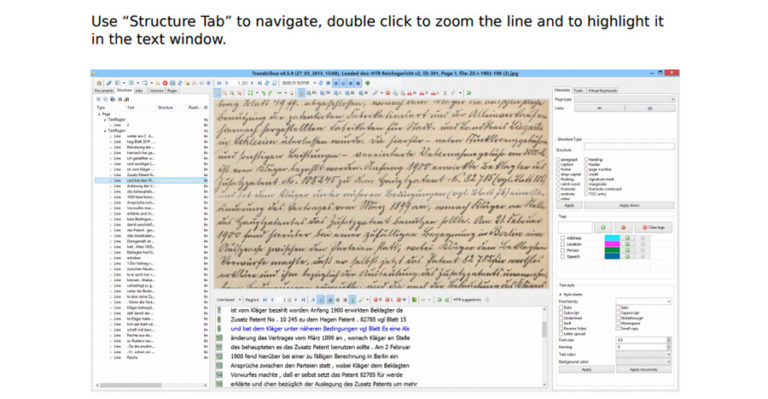

In week three of my placement, I was introduced to Transkribus and Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR), supervised by Louise Seaward (Academic Engagement Manager). Transkribus is a highly innovative programme through which it is possible to train models to transcribe handwritten text. I was fascinated by this technology, and it’s a huge help to researchers who now no longer need to perform the time-consuming process of transcription themselves.

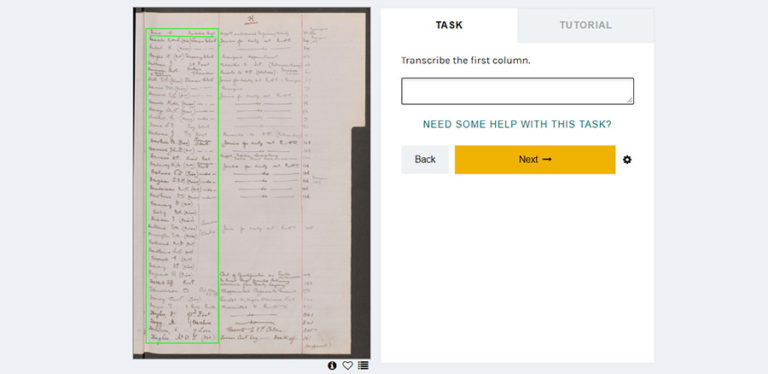

For the second half of my placement I worked with the data produced by the transcriptions of the War Diary records, as part of the Operation War Diary project, supervised by Mark Bell (Digital Researcher) and Bernard Ogden (Research Software Engineer). Crowd-sourcing is an important part of the process of converting physical documents into digital catalogues. Zooniverse, a crowd-sourcing platform, enables users to create crowd-sourcing projects, including workflows, which set out a series of tasks necessary for contributors to take part in the project. In addition to creating my own workflows on Zooniverse, I was also introduced to the process of data cleansing, which involves identifying and removing or correcting errors and inaccuracies within the collated data.

For the final week of my student placement I continued to explore Operation War Diary, assessing the quality of the reconciled data by comparing the data produced in Zooniverse with the data transcribed manually in Transkribus. The two sets of data, produced from the same original records, showed a number of inconsistencies and errors. This raised several questions about the reconciled data, including the classes of errors and why these errors may impact how the data can be used.

Overall, this process demonstrated that, in comparison to Transkribus, Zooniverse is more suited to distant reading, which allows a larger quantity of data to be read but in less detail.

This six-week placement was a hugely rewarding experience. I learnt a great deal about the archival sector, but also about the unique nature of The National Archives as a government department. I highly recommend a student placement with The National Archives, not only to those interested in archives but to anyone interested in the Arts and Heritage sector more widely.