Archival documents are multisensory objects, and interacting with them is a multisensory experience. How they feel, what they smell like, and the sounds they make when we handle them offer insights into their materials, production, condition, and history.

In my work at The National Archives, I recently undertook an exploratory project to investigate how the senses can be used to access, engage with, and understand the materiality of archival collections. How can we engage with and understand a document or object beyond sight, beyond reading its contents?

In asking this, I hoped to elevate the materiality and sensory physicality of archival collections and discover alternative and more inclusive ways audiences can access, interact, research, and understand them.

Across two blogs I’ll share my experiences from my project, starting with our collection.

As a member of the Collection Care team, I utilised the materiality knowledge and sensory skill set of my conservator colleagues to uncover the multisensory characteristics of our archival documents. Through informed touch, smell and listening, our documents come alive. Below are examples of using this approach with materials and documents found within our collection.

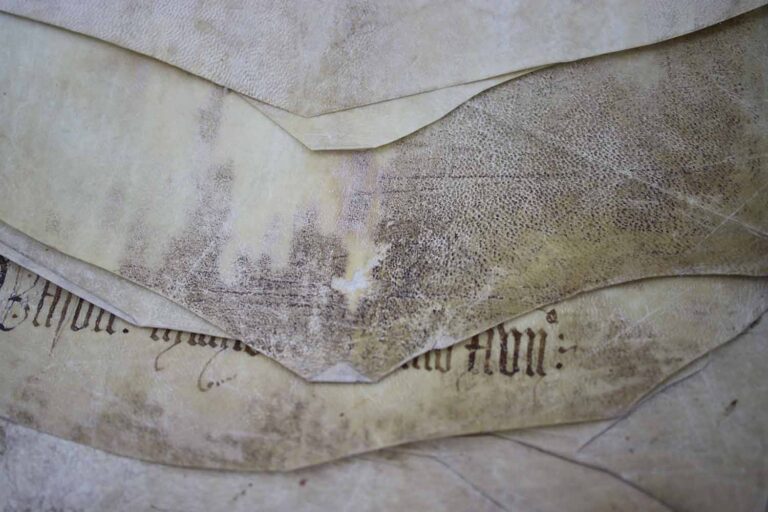

Parchment

How rough or thick parchment feels can indicate its production process and quality. The smoother, silkier and thinner the parchment feels, the higher quality it is. On lower quality parchment, it may still be possible to see outlines of the animal’s veins or feel its hair follicle pattern.

The stiffness or flexibility of parchment, and the sounds it makes as it is turned or unrolled, can additionally indicate its condition and care needs. Parchment is what’s known as a hygroscopic material. When there is less moisture in the air, parchment starts to contract; when there is more moisture in the air, parchment can over-relax and become limp. All these factors impact the individual sensory experience of interacting with parchment documents.

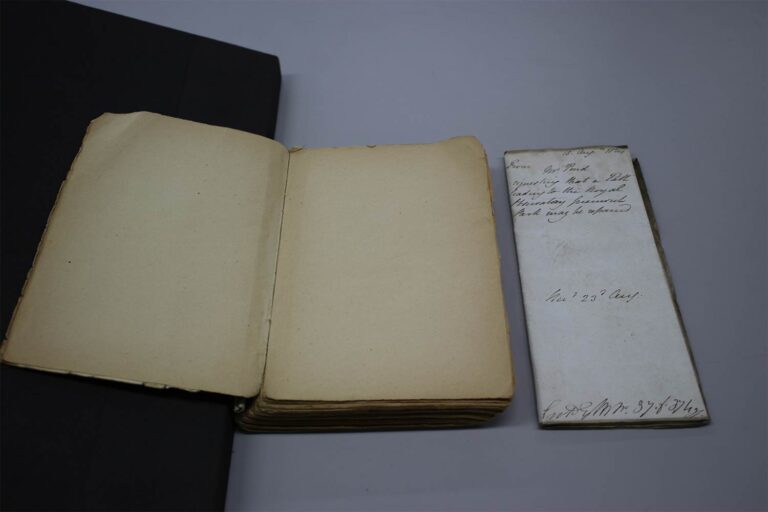

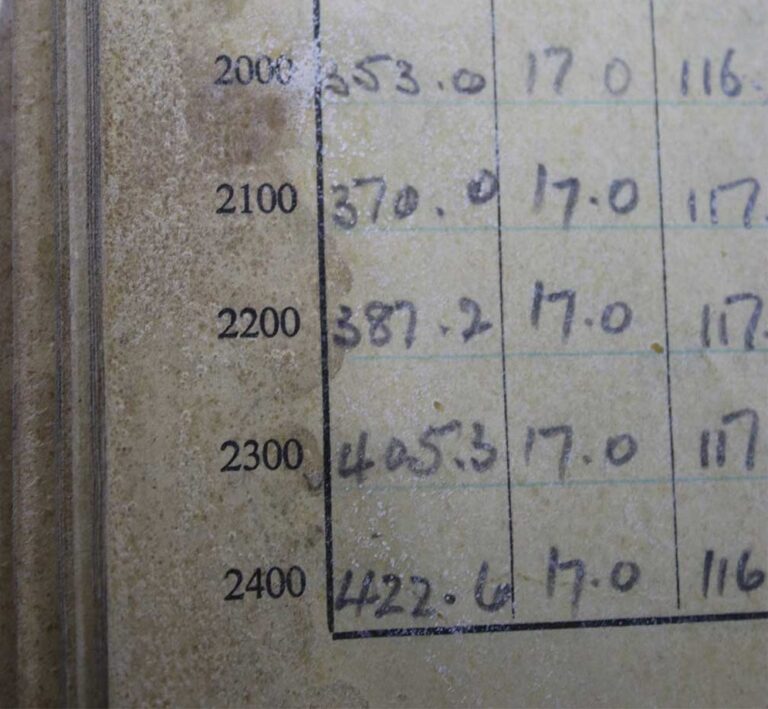

Paper

Turning to paper, the feel, sound (or ‘rattle’) and smell of different types of paper produces different sensory experiences. Older European paper made from linen or cotton rags feels strong and thick to the touch. Made from plant materials with a high percentage of cellulose, they remain largely stable as they age.

In comparison, the involvement of chemicals in the manufacture of modern papers, particularly wood pulp paper from the late 19th century, makes these papers feel thin and they can tear more easily.

Wood pulp paper contains a lot of lignin, which decays quickly as it oxidises, breaking down into acids that eat away at the paper’s cellulose. This acidity and decay make the paper feel brittle to the touch and releases volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which can be identified through different smells. This includes vanilla (due to the breakdown of lignin, which emits benzaldehyde and vanillin) or a sweet, almond-like fragrance (caused by the decay of cellulose which emits furfural).

The odour profile of different kinds of paper has been analysed and mapped by researchers, with smells being matched to the degradation of certain substances within the materiality of the paper.

Oily paper

Within our Ships’ Logs series is a peculiar collection of 20 ‘smelly’ documents. First identified through the rancid smell they emitted and waxy touch, using scientific analysis these documents were discovered to have a coating of spermaceti wax (wax from the head of a sperm whale).

The smell was deemed so potent that the Collection Care team had to remove some of the wax to make the documents accessible in our reading room. Nevertheless, these sensory qualities remain central to the experience of interacting with them.

Microfilm

Smell is a key identifier of the condition and degradation of our large microfilm collection. Between the 1950s and mid-1970s, cellulose acetate (a plastic) was commonly used as the base layer on microfilm.

As it ages, cellulose acetate becomes increasingly acidic; a telltale sign of degradation is the smell of vinegar. Known as ‘vinegar syndrome’, this recognisable smell is caused by the release of acetic acid (a key ingredient in vinegar). This chemical vinegary smell indicates the poor condition of the microfilm inside its box, which shrinks and becomes brittle as the film ages and degrades. Once started, this degradation process cannot be stopped; it can only be slowed by cold storage.

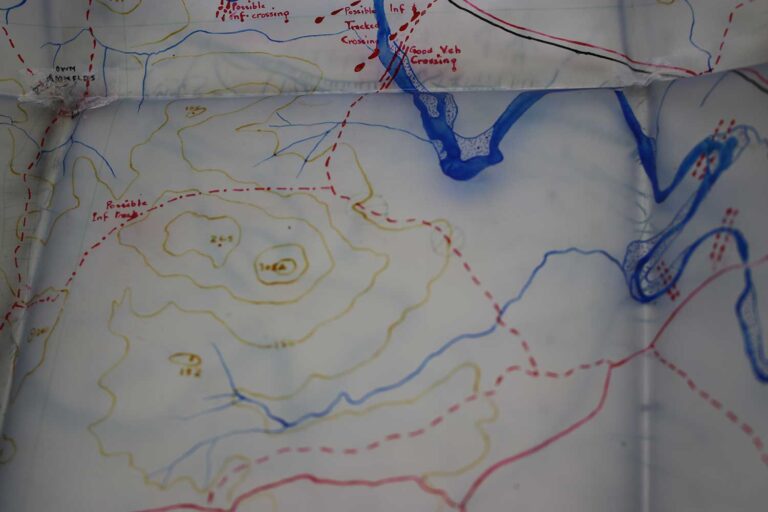

Modern materials

The sensory qualities of plastic, including its sound, rigidity, and resistance when handling, provide information as to its condition and how to handle it safely. For example, plastic overlays for paper maps to chart the progress of battle plans are found within our Second World War records. Stored folded, the loud, crinkly sound as it is unfolded, and its resistance upon opening to lay flat indicates how best to handle and access this material.

This is just a small peek into the materiality and multisensory characteristics of documents within our archive and how we can access and understand them through using our senses.

Look out for part two of this blog series. In this, I’ll explore the different ways of working with the senses in an archival environment and the opportunities and benefits of this approach to widening access to our collections.

I’m also putting what I’ve learnt into practice by producing sensory displays. Throughout October you can visit The National Archives and use touch, sound and smell to explore the material story of this month’s Stories Unboxed.

I have found this subject very interesting and will help me to understand the best way to protect our family documents for the next generation.

What a fascinating article. I have a very old family bible with lots of faded family births deaths etc unreadable writing on the title page. I can’t bring myself to throw it out. I would dearly love to obtain a clear image or transcript. Could you give me some ideas as to where I could get this done.