During the past few months, we have been developing an archival data model with the aim of making it flexible for our own potential future needs and accessible for all of our users. (See our previous posts Modelling our digital archival data and Digital archiving: the seven pillars of metadata.)

A diverse group of people within the organisation has been involved in this project, ranging from some of the top experts in the field to laypeople like me. I began my work as an apprentice here roughly a year ago. I had no prior knowledge or understanding of how an archive would function, so from the start I have devoted a lot of my time to researching archival terminology and concepts. I have found this to be a benefit in modelling our archival data, allowing me to lend a fresh pair of eyes and a digital-first point of view to the project.

We are now at a point in the project where, through a collaborative and iterative process, our model has taken shape into a solid first draft.

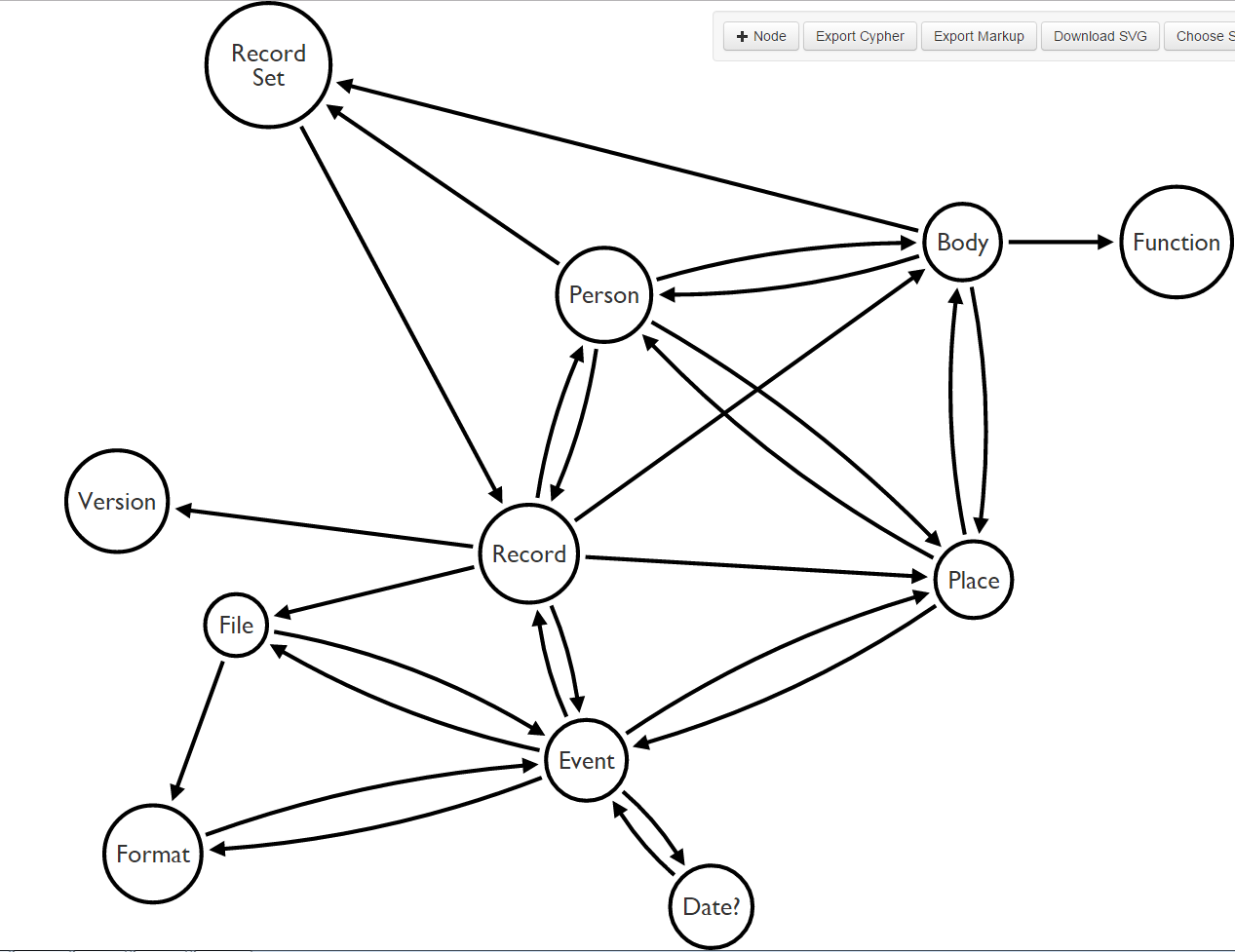

First draft of the model.

Personally, I do not believe that our first model iteration (pictured right) is sufficiently flexible or accessible: I have personally been coming across a number of challenges over the past few months working on this:

- difficulty understanding archival terminology and concepts (like ‘Record Set’ and ‘Series’) affecting accessibility to those not already accustomed to archives

- the inflexible and deep roots of physical archival structure in everything we do, even in our digital offerings

To pick apart the first challenge, I must share some of the archival terminology used at The National Archives which I have struggled with, and my current understanding of it:

Collection

This is an artificially created compilation of documents/records, based on a categorisation that an archivist deems significant.

Set/Series

This is a compilation of documents/records, which are generally curated based on their natural provenance (see below) by the records creator.

Provenance

The organisation where the records come from and the reason why they have been created.

Record /Document

The archivally significant item in question.

File

A unit of documents gathered together.

First off, the word ‘provenance’ is not necessarily immediately recognisable to a layman, but the concept behind it is generally understandable. The dictionary defines it as ‘the place of origin or earliest known history of something’ – so, at its core, it represents the relationship between things and places.

Secondly, the archival definition of the word ‘file’ is now very distinct from the general understanding of it. This may be because of the increased use of ‘file’ as a way to refer to a digital file (such as a word document or a PDF) rather than a container for a set of documents; so the term ‘file’ should be reserved primarily for its common usage and not the – now fringe – archival definition.

Similarly, to the above points, I suggest that removing the idea of a ‘collection’, ‘series’, or ‘record set’ from our model would go some way to making it easier to comprehend the wealth of information we have available. When I first started using The National Archives’ online catalogue (Discovery), I had a large amount of confusion surrounding these concepts; they are simply unintuitive in a world where people are used to searching for the information they need (via Google and other modern search services) by keyword, rather than inputting adjacent terms and contexts.

But what would the series be replaced by? Perhaps it would help users to understand records more effectively if – like the aforementioned modern search services – we allowed documents to be naturally collated by their relationships to multiple contextual elements (provenance, time, people, content, form, subject, etc.)

This segues nicely into the second challenge I faced – the tight grip of paper archiving methods upon our current conceptual model. If we remove the very physical concept of a ‘collection’ or a ‘set’ to store a record in, what does the record become? And what can it be sorted by?

If we isolate the record, provenance, time, people, content, form, and subject into their own separate items, we wouldn’t need to establish the same inheritance or hierarchy. The records will stand as items of data in their own right (with relationships to other records, of course), allowing users to access our data in a far more digital-first way.

We can go even further in the conceptualising of these, and divide the ‘record’ into

- The physical/digital manifestation of the record

- A digital file (for example, DOC), which contains five pages in Microsoft Word Document format

- The conceptual idea of the record

- The knowledge that this Word document is ‘Job Seeker’s Allowance Interventions, chapter 7: missing labour market units’, and the entire surrounding context which follows from that

In the interest of using accessible terminology, the actual manifestations of the record can be referred to as the ‘file’, in keeping with the common definition of the word ‘file’. The conceptual idea of the record we can continue to refer to as the ‘record’, representing the archival significance of the ‘file’.

If we do away with all of the constraints of the physical box (‘collection’/‘series’/‘record set’) on our digital data, we are left with a number of important contextual elements:

- records

- files

- people

- places

- events

- bodies/organisations

- functions/tasks

- formats

For instance, Vellum copy of Shakespeare’s will – ER1/49/4 (the ‘Record’), Stratford-upon-Avon (the ‘Place’), and The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust (the ‘Body’) all actually exist independent of one another, with important contextual relationships between them supposing that one came from the other.

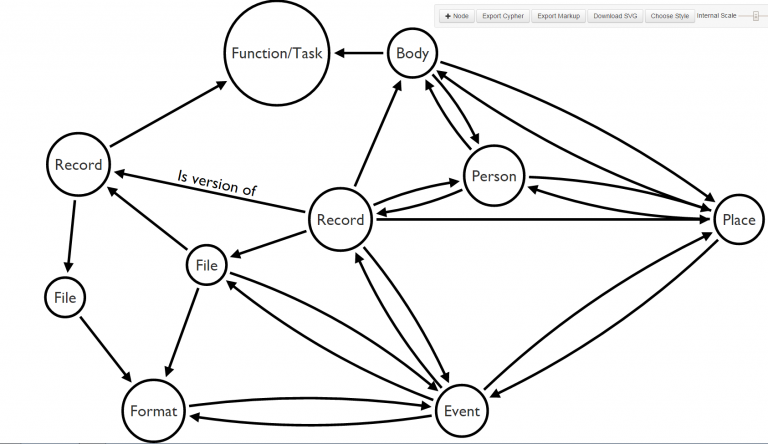

So, this presents a beginning point of eight entities to include within the first iteration of the model; this may be subject to change as it is applied, but it comprises a suitably generic starting point, nonetheless.

In this example of my proposed model you can see how, with the must-have entities modeled, a record could be given both context and form.

Relationships will be the richest and most varied part of the graph as – reflecting real life – they are the contextual links between everything. Naturally, from linking elements with the truthful representation of their relationships, we can expose and explore implicit ‘series’ without a need to impose the physicalised concept of a ‘set’ (as a sort of ‘box’ or filing system) onto digital media.

Somewhat counter-intuitively, in order for this model to be as extensible and flexible as possible, these relationships should not be explicitly outlined until it comes to the point of implementation – there are likely to be far too many to plan for!

The rich, detailed context that these relationships supply will handily lend itself to natural language queries, and not just those relating to the title or description of a record. If one wanted to find all of the records of a particular event, from a particular date range, involving a particular person, they could effectively query that information.

Hopefully, this will help people to find and understand the records that they want to look at; closely related to this is a PhD study currently being undertaken at The National Archives to gain insight into ‘users’ mental models of digital archives’, studying our user bases’ understanding about the concepts introduced by archives.

Finally, while researching concepts, I have found myself wondering whether we are doing enough to fulfill our duty to public access in regards to our terminology/conceptual structure. Should we be seeing this as an opportunity to seek out those paper foundations on which we have built our online catalogue, and develop them as a more conceptually understandable, digital-first search tool?

This post made for very interesting reading, as with the previous posts linked in the article.

As a Records Manager, I see there is potentially a case not for just an archival centric data model or perhaps knowledge-graph, which is what this post appears to be describing to some extent, but also a case for whole-of-archival-jurisdiction knowledge graphs that can be utilised not only describe archival collections at an object or content level, but also be incorporated by creating agencies into metadata models and semantically embedded in documents from the very outset.

Being able to utilise a flexible, yet, singular semantically rich knowledge description framework that could be applied at the object level, or be embedded at the content level from the time of creation onwards and remain useful right through to and during the archival phase is perhaps a distant dream, however!

To my way of thinking, it would seem to be aligned to the Records Continuum model, and the Information Continuum Model published by Upward et al (2018) in supporting information objects from the create to the pluaralise dimensions. On a practical level, it is arguably, perhaps not too conceptually dissimilar to the role Wikidata is evolving into in its relationship with Wikipedia projects in describing the knowledge contained in WikiPs millions of ‘documents’ and supporting discoverability of that knowledge via various means.

Personally, I see there is a strong potential role for archival bodies to play in mapping out these models at a higher level for their jurisdictions and extending them to content long before it arrives at the archive.

Looking forward to future posts on this subject.