By far the most destructive of all the myths to emerge from the story of the Dunkirk evacuation is that the British abandoned their French allies at Dunkirk, both literally and metaphorically. In fact, documentary evidence provided in WO 106/1613 suggests that British military and naval chiefs overseeing the evacuation were resolutely committed to saving French 1st Army soldiers who were stranded at Dunkirk, alongside the men of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

The origins of this dispute, perhaps, stem from a difference in terms of how both Allies viewed the Dunkirk Salient from the start. Firstly, the British were intent on evacuating from Dunkirk from the beginning, and since both the French and the BEF had conducted their own separate retreats and were manning their own sections of the Dunkirk perimeter, the Admiralty simply assumed that the British would evacuate BEF troops in Royal Navy ships, while French soldiers would be evacuated in French ships. Secondly, the French army and navy had intended the opposite of an evacuation; Admiral François Darlan, the Chief of Staff of the French Navy, supposed that the Dunkirk beachhead could be sustained in order to become a continuous threat to the German flank.

It was not until 27 May, the day after Dynamo had commenced, that the French realised that the BEF was being withdrawn from Dunkirk. Faced with this new situation, for which they were quite unprepared, the French were forced to revise their plans. They had already gathered a force of hundreds of French trawlers as part of the resupply effort, which would now be used for evacuating troops, but they lacked warships of their own.

The reason few French warships were available at Dunkirk was because of an agreement between Royal Navy and French Navy commanders concerning theatres of responsibility; this arrangement had, thus, resulted in much of the French fleet being stationed in the Mediterranean. Now, the Royal Navy would have to shoulder the responsibility for evacuating the French, as well as the BEF, from Dunkirk[ref]Walter Lord, The Miracle of Dunkirk (London: Wordsworth Military Library, 1998), pp. 174-5.[/ref].

Despite British willingness to help their French allies, the most undiplomatic figure of the Anglo-French military and naval coalition was none other than the commander of the BEF, Field Marshal Lord Gort, whose scathing remarks and dismissiveness of the French martial ability throughout the Battle of France possibly helped drive a wedge between the Allies.

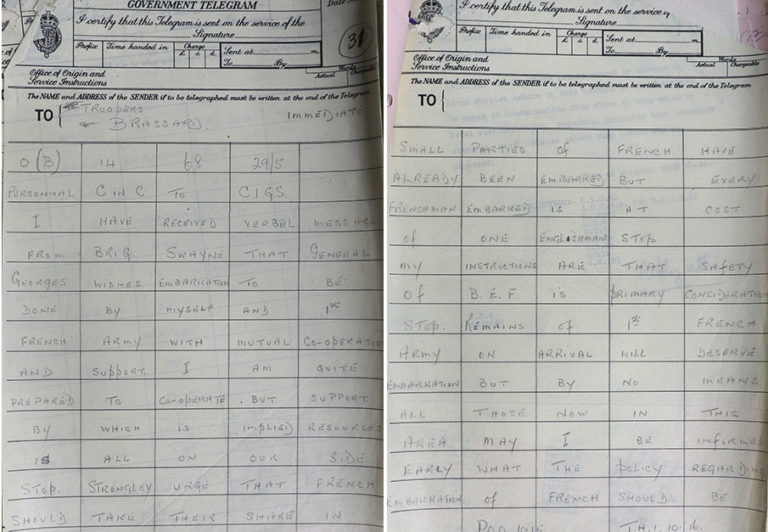

When Gort first learned of the arrangements for the French at his headquarters at La Panne on 29 May, he immediately telegraphed the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Sir John Dill, to ask for clarification on whether French troops were to be evacuated alongside British troops in equal numbers. Gort reminded Dill that the safety of the BEF was his primary consideration: ‘every Frenchman embarked is at cost of one Englishman’ (WO 106/1613).

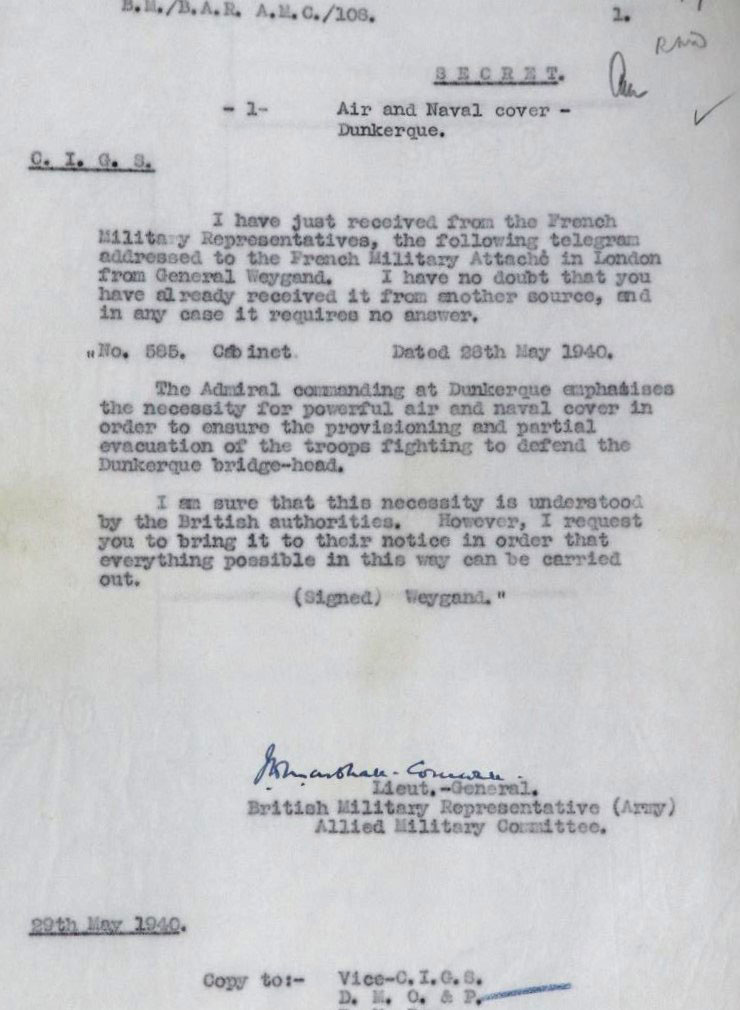

Despite Gort’s lack of diplomacy or care towards the French, Dill knew that Britain had to do its best by its ally. That same day, Dill received a telegram from the British Military representative to the Allied Military Committee. The telegram contained a message already conveyed to the French military attaché in London from General Maxime Weygand, the French Chief of Staff, requesting immediate British air and naval support for French rearguard troops who were, at that moment, defending much of the Dunkirk perimeter (WO 106/1613).

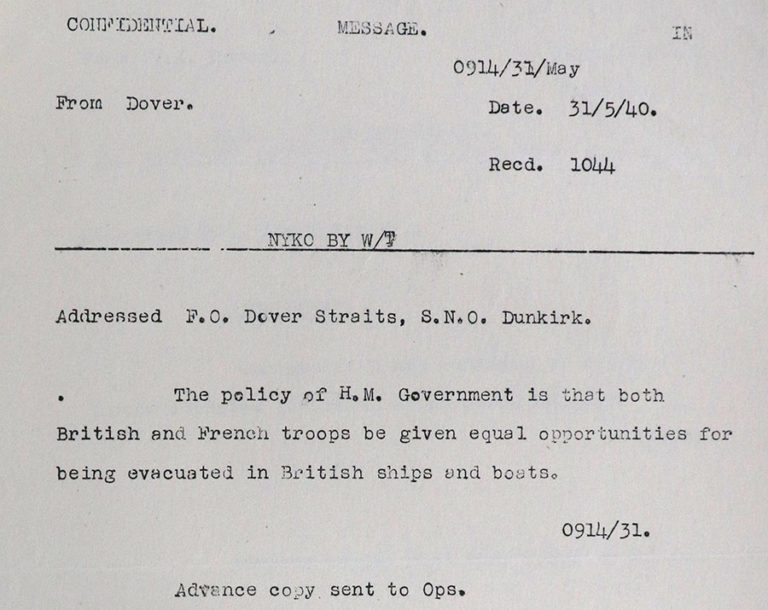

Evacuating the French thus became the informal policy of the British, but this clearly was not properly communicated to Royal Navy officers coordinating the evacuation at Dunkirk at first, leading to understandable confusion and a flaring of tempers. However, on 31 May, the British War Cabinet’s decision, communicated directly to the Senior Naval Officer at Dunkirk, Captain Bill Tennant, was that French soldiers were now to be evacuated alongside BEF troops in equal numbers (WO 106/1613).

Sadly, this act of goodwill by the British government was let down by Lord Gort upon his departure from Dunkirk. Leaving France without any word of farewell to General Weygand, he turned to the French liaison officer accompanying him and expressed his ‘astonishment’ at the French Army’s lack of willingness to fight[ref]Brian Bond, The Battle for France & Flanders: Sixty Years On (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2001), p. 94.[/ref].

On top of this insult, Gort’s instructions to his relieving officer, Major-General Harold Alexander, brought the British senior officers overseeing the evacuation into conflict with their French counterparts, particularly General Bertrand Fagalde, the commander of the French 16th Corps, and Admiral Jean-Marie Abrial, the French senior naval officer at Dunkirk.

Alexander’s orders from Gort were to withdraw all remaining British forces, but he faced a situation where he was expected by the French to commit three British divisions to the defence of the Dunkirk perimeter. Alexander rejected these orders, arguing that these British divisions were depleted and exhausted, and that Gort had issued conflicting instructions for them to be evacuated. This unfortunate disagreement further soured Anglo-French relations[ref]Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Dunkirk: Fight to the Last Man (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), p. 407.[/ref].

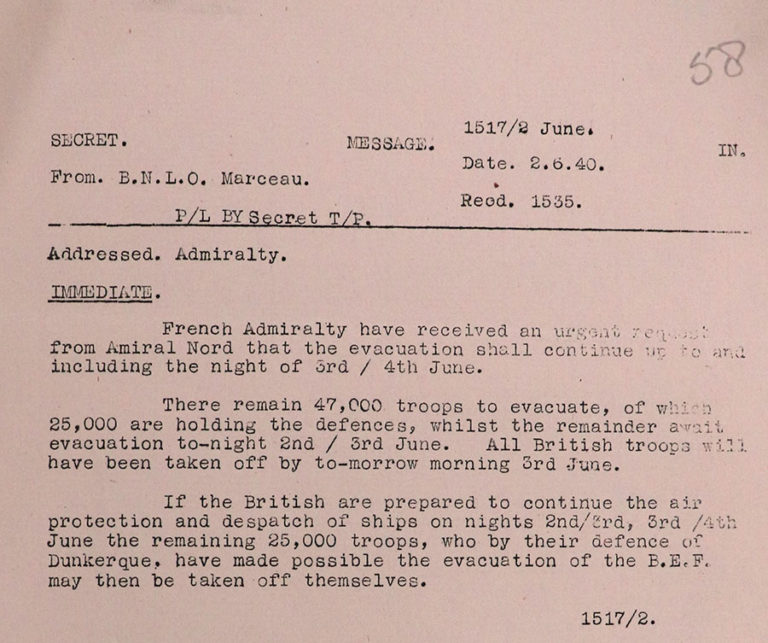

However, by the close of the evacuation, the British were determined to make sure that the French rearguard force, which were largely responsible for protecting the Salient, would be carried off safely. A British Naval Liaison Officer seconded to the French Navy communicated an urgent request directly from Admiral Abrial on 2 June. The evacuation of the BEF was to be concluded that night, but Abrial had requested that the Royal Navy return to save the French rearguard on the night of 3rd/4th June. There were an estimated 47,000 French troops remaining in the pocket, of which 25,000 were directly engaged in the defence of the port (WO 106/1613).

Whereas the saving of the BEF gave considerable cause for rejoicing, the saving of the French became a matter of honour. General Alexander, on his return from Dunkirk, had a phone conversation with the War Office in which he conveyed his concerns for British wounded that had been left behind at Dunkirk. Alexander also argued that many French had been left behind, and to not return for them would be construed as ‘a breach of faith’.

Admiral Ramsay assured Alexander that he would do what he could for the remaining French[ref]WO 106/1613, Record of Phone Conversations with Generals Alexander & Lloyd, 3 June 1940.[/ref]. Accordingly, Ramsay issued instructions to destroyer and minesweeper crews involved in the operation, to prepare themselves to go across the English Channel one last time for the sake of their ally: ‘We cannot leave our Allies in the lurch, and I call on all officers and men detailed for further evacuation tonight to let the world see that we never let down our Ally…’[ref]Sebag-Montefiore, Dunkirk, p. 448.[/ref].

On the night of 3rd/4th June, a reduced force of Royal Navy warships crossed to Dunkirk and evacuated French soldiers waiting on the Mole. Unfortunately, not all of the rearguard were able to withdraw to the harbour in time. On the afternoon of the 3rd, German forces had reached Rosendal, at the entrance of the town. That same afternoon, the French ran out of ammunition and were virtually unarmed[ref]WO 106-1613, Admiral Ramsay (Vice-Admiral Dover) to Admiralty: Admiral Abrial’s message, the closing Dynamo & dispersal of task force, 4 June 1940.[/ref].

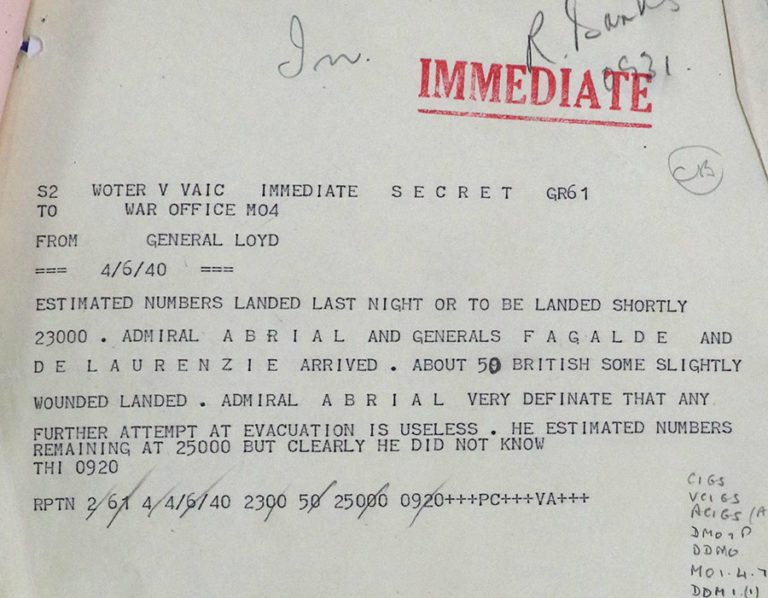

That night, Ramsay’s ships evacuated an estimated 23,000 French troops and personnel, including General Fagalde and Admiral Abrial, along with 50 British wounded. However, tens of thousands of French had been left behind, along with thousands of British wounded; Abrial himself estimated that some 25,000 remained, but he did not know for sure.

Crucially, Abrial himself was ‘very definite that any further attempt at evacuation’ would be useless. Thus, it was at the word of the senior French naval officer at Dunkirk that Ramsay decided to terminate Operation Dynamo (WO 106/1613).

The myth of the abandonment of French troops by the British at Dunkirk has, arguably, been perpetuated over the course of many decades. It owes its existence to an ignorance of how many French troops were rescued at Dunkirk: just over 112,000 French soldiers and other allied personnel were lifted by the Royal Navy during Operation Dynamo, alongside 225,000 troops of the BEF[ref]WO 106/1613, Evacuation of Dunkirk Area: Total number of troops (British, Allies, Fit, Wounded) evacuated from 20 May to 4 June, 1940.[/ref].

The fact that many of these evacuated French troops ended up being returned to France, after barely a week’s pause, to face the Germans again, followed swiftly by the defeat of their country, deprives the French of any sense of victory from this event. Furthermore, the Dunkirk evacuation, though widely celebrated in Britain, attracted a ‘chorus of condemnation’ in France[ref]Martin S Alexander, ‘Dunkirk in military operations, myths and memories’ in Robert Tombs & Emile Chabal (eds.) Britain and France in Two World Wars: Truth, Myth and Memory (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), p. 99.[/ref]. Evidently, this feeling has never left French society.

Although Dunkirk may have been miraculous in the eyes of the British public who saw their soldiers returning safely home, France had to wait another four years for their ‘miracle of deliverance’. In the midst of this hubris, the story of the French troops who were saved at Dunkirk became lost in time, as did the memory of how their British allies endeavoured to save them.

See also: The Dunkirk Evacuation – Part 1: Where was the RAF? and The Dunkirk Evacuation – Part 2: The heroism of the Royal Navy.

The whole issue of the Fall of France was that their military planners were basing their defence on the First World War and by the time Sedan fell here was no real hope. The French governments had only them selves to blame, building the incomplete Maginot Line was an expensive folly and the British comments at the time of Dunkirk are typical of the Anglo-French rhetoric ever since.

The comment ‘only them selves to blame’ (sic) could be extended to cover Britain as well as France in the sense that following the huge loss of life endured during the First World War there wasn’t the will to challenge the rearmament of Germany.

However it is a sad truth that France – confusef over its responses to Germany ignoring the post-WW1 treaties, reorganising its aero industries continuously which hampered development and supply of military aircraft while overlooking the potential of tank warfare – appeared to fight the Second World War as it had the First World War two decades earlier. Once again individual heroism and collective love of ‘La Patrie” often marked their actions.

It should be remembered that Britain and France had similarities in their journeys to Dunkirk but far, far more differences stretching back to before the beginning of the 20th century in everything from the class system to military call-up, collective military experience and what now would be described as ‘world view’.

Too much evidence of hindsight reduces the credibility of this direct criticism of British indifference to the fate of French troops at Dunkirk. It amounts to hostile bias!

Additionally it was used recently as retrospective anti-British criticism by a contributor to the “Quora” website.

Where is the telegram from Winston Churchill to Field Marshal Lord Gort?

I have often Heard how the brave British fought a fierce rearguard at Dunkirk but rarely are we told that forty thousand French troops held off the German army while we escaped. Also, ninety thousand of the rescued French voted to return to surrender and Churchill wrote ti let them go as they would be useless mouths to feed