‘I don’t feel male or female or anything. I don’t even feel human.’

With these immortal words, Rachael Blackmore entered sporting folklore. On Saturday 10 April 2021, the Irishwoman crossed the finishing line at Aintree on Minella Times to become the first female jockey to win the Grand National, the world’s most famous horse race and one of the world’s most watched sporting events, in its 182-year history.

Before her victory, just 32 horses with female riders had competed since Charlotte Brew rode in the most celebrated running, Red Rum’s unmatched third victory in 1977. Female participation has long been controversial due to the perceived extra dangers of the race for women and comparative abilities of male and female riders – Red Rum’s legendary trainer Donald ‘Ginger’ McCain infamously remarking in 2005 that ‘Horses don’t win Nationals ridden by women; that’s a fact’ (see footnote 1). Rachael Blackmore emphatically put such views to rest and arguably gave the race its greatest highlight.

The Grand National has always had a difficult history. In the three decades after the Second World War, it faced an existential crisis: failing facilities, dwindling attendances and opposition from animal rights activists brought about attempts to sell the racecourse for development. That it endured was due in no small measure to another talented, indomitable woman whose tenacious stewardship and colourful advocacy prevented its loss from its Merseyside home, and from being consigned to history. Much of the political background to this story survives in files housed at The National Archives (footnote 2).

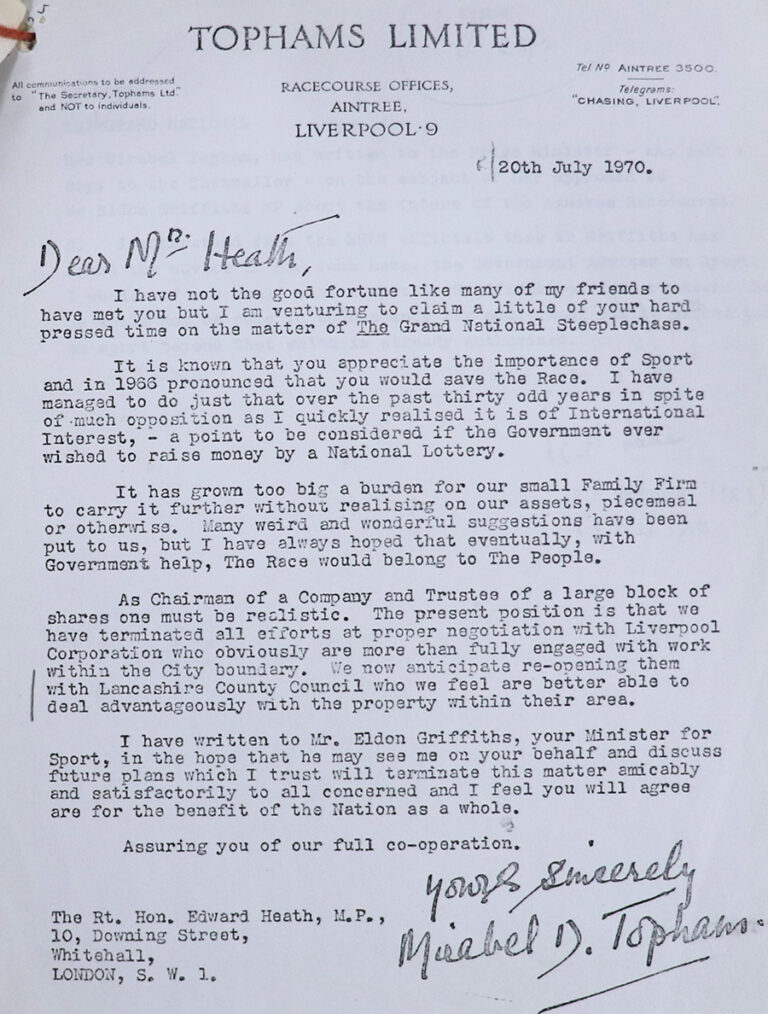

On 20 July 1970, Mirabel Topham wrote to the Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath a month after he had surprisingly defeated his Labour predecessor, Harold Wilson, in that year’s General Election:

‘It is known you appreciate the importance of Sport and in 1966 pronounced that you would save the Race. I have managed to do just that over the past thirty odd years in spite of much opposition as I quickly realised it is of International Interest.’

The crux of the matter was that:

‘It has grown too big a burden for our small Family Firm to carry it further without realising our assets, piecemeal or otherwise. Many weird and wonderful suggestions have been put to us, but I have always hoped that eventually, with Government help, The Race would belong to The People.’

Since 1938 Mrs Topham had been Managing Director of Tophams Ltd, long-time managers of Aintree racecourse north of Liverpool, an unusually prominent woman in sports administration. A Londoner by birth and former child actor on the West End stage, Topham had married into the family in 1922, quickly immersing herself in managing, promoting and staging the world’s greatest steeplechase (footnote 3). In 1949 she had cannily purchased the freehold of the 270-acre course from Lord Sefton for £275,000.

But her self-declared, one-woman campaign to make the racecourse financially viable and the race sustainable for the public looked in serious danger of failing. From 1964 she had unsuccessfully tried to divest the company of the racecourse, and had consistently but equally unsuccessfully tried to leverage financial support from the Wilson Government, while simultaneously generating sufficient finance and goodwill for her stewardship of the race to continue. Her appeal to Heath aimed to conclude the campaign profitably.

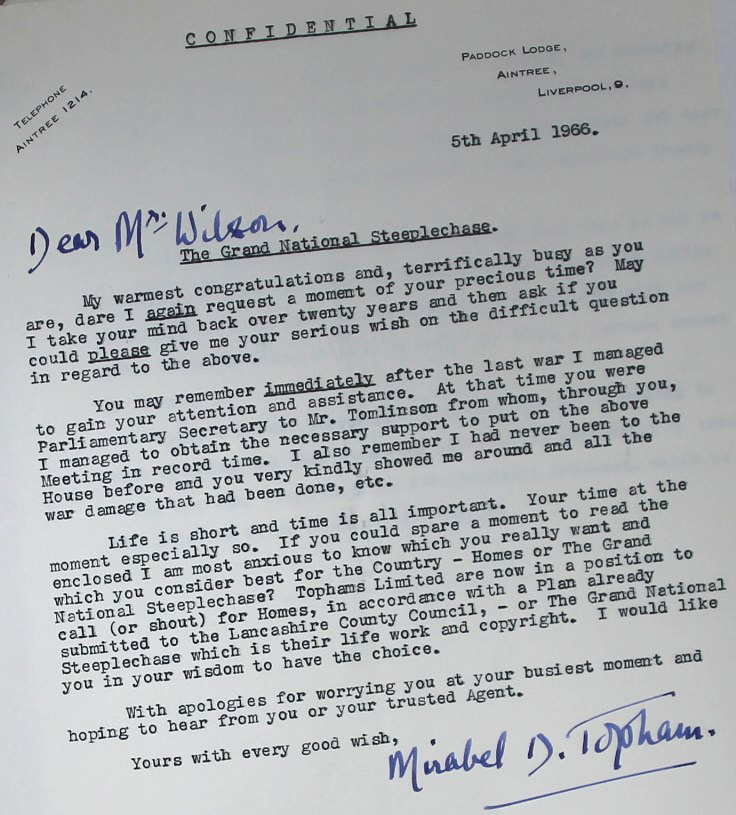

Matters had first really come to a head in the early spring of 1966. As she would do repeatedly in her campaign, Topham wrote to Wilson on 5 April, offering her ‘warmest congratulations’ on his landslide election victory of 31 March and asking for his ‘serious wish’ on the business under discussion for over 20 years. She reminded the PM that just after the war, as Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Works, he had assisted her in running the first Grand National ‘in record time’ and shown her around the bomb-damaged parliamentary estate. She asked him to decide:

‘which you consider best for the Country – Homes or The Grand National Steeplechase? Tophams Limited are now in a position to call (or shout) for Homes, in accordance with a Plan already submitted to the Lancashire County Council, – or The Grand National Steeplechase which is their life work and copyright.’

In 1964 Tophams had submitted a planning application to Lancashire County Council (LCC) to sell 70 acres of the Aintree racecourse to a London property developer for c. £900,000. Falling attendances at regular race meetings, contributing to a decline in facilities and amenities, meant that by the early 1960s only the three-day Grand National meeting was staged. A concerted public and parliamentary campaign by animal rights groups, including the moderate RSPCA and the more radical League Against Cruel Sports, had additionally highlighted the conditions of the race which had caused fatalities, injuries and small numbers of finishers in several runnings in the 1950s. Spearheaded by the radical Conservative MP Howard Johnson and the Labour peer Lord Ammon, a petition with 170,000 signatures was submitted to the sympathetic Conservative Home Secretary R A Butler in 1959. The race should be made less challenging by modifying the height and spread of severe fences, reducing the number of fences, revising qualification conditions and limiting the field to 20 runners (an obvious but unstated disincentive to the betting market).

Topham had expressed her disappointment that Butler met representatives (and considering them ‘reasonable and well-informed’), arguing the course was ‘strenuous but fair’, and that ‘If all the proposals made by the critics were adopted there would be no race’ (HO 285/6, ANM 13/1/61). As Butler himself noted, while he could not agree with Ammon that the Grand National represented ‘an orgy of cruelty in the guise of sport’ (ANM 13/1/57), his sense that the refusal to make even minor modifications (‘There is no question of our changing or modifying the course. I think that would upset the character of the race.’) would have an adverse psychological affect in public opinion.

Ultimately, the Tophams’ appeal to the House of Lords against a ruling procured by Lord Sefton against the sale of land for housing proved successful on 30 March 1966 (HLG 131/615, p. 1). Nevertheless, LCC blocked planning permission at subsequent meetings. The local political context played heavily on Wilson. Writing in 1968, George Wigg, former Paymaster General, reminded Wilson that ‘Almost the first thing you asked me to do when we took office in 1964 was to talk to Eric Heffer (who had gained Liverpool Walton in the 1964 Election) and Alderman Sefton about the problem of Aintree and the future of the Grand National.’ In the background, an ad hoc committee had then worked to save the race, negotiating with Mirabel Topham on a confidential agreement for her to continue running the race until 1970 ‘on condition that no announcement was made of her intention so to do’.

On 18 April 1966, Harold Wilson wrote to Richard Crossman, Minister for Housing and Local Government, asking him to take a closer look, firstly as the course was close to his Huyton constituency (footnote 4) and he was interested in its future, and secondly:

‘I do not think that the future of the race is a matter in which we need concern ourselves very closely though the future of the course is a matter which we ought to consider since it will affect housing development and other amenities in the Liverpool area.’

PREM 16/3290, PM 17/66

Wilson faced a sticky situation. Regional development for housing had been a principal plank in Labour’s local government strategy, but to move the Grand National or be seen to sit aloof while a race with such history and connection to the northwest could wither and die would be politically catastrophic. He was also unsure of Topham’s motives. In a meeting with George Wigg on 12 April 1966, she had apparently revealed her original plan to transfer the race to Ascot, which had modern equipment and could easily be adapted to preserve its character, claiming ‘After 5 years the name of Aintree would be forgotten though the Grand National would remain’! Topham clearly irritated the horseracing fan Wigg. He is said to have described her as ‘a rather odd character who was liable to plough up Aintree at any time’ (PREM 13/3290, minute to Malcolm Reid). Worse still, a scheme involving LCC and Liverpool City Borough, with provisional backing from government ministers, for conversion of the racecourse into a regional sports centre was derisively rebuffed by Topham. She reportedly scoffed that it would be in competition with Butlin’s plan for Blackpool and would refuse to run the race there under such circumstances:

‘though she would be willing for herself and her family to run the Grand National for a fee. It seems that Mrs. Topham considers that she has a prescriptive right to the title of the Grand National, the race having been originated by her husband’s grandfather about 125 years ago.’

The ad hoc committee referenced by Wigg in 1968 had been convened in April 1966 under the chairmanship of Crossman and included Denis Howell, Minister for Sport, and senior representatives of LCC and Liverpool County Borough Council (PREM 13/3290, 26 April 1966). Over two years officials of the departments of Housing and Local Government, Education and Science and the Treasury evaluated the possibilities of a sustainability plan for the Grand National and to provide an area that could be developed to generate revenue. Their diligence, while maintaining contact with the Tophams alongside their concurrent negotiations with, first both local authorities over the purchase of the course at an inflated price, produced an ambitious scheme. It revolved around the development of a regional sports centre costing c. £3 million, and the lease of the course and racing rights to an independent, non-profit committee. Howell announced the plan in a statement to Parliament on 2 July 1968 (footnote 5).

As with many other capital projects in the late 1960s, however, the constraints on public expenditure imposed by Chancellor James Callaghan dampened these ambitions. Detailed, tortuous conversations during this period had confirmed that no private investor would buy the course, particularly as the Grand National could not be divorced from the land development and ‘Mrs. Topham is disposed to make her agreement to sell conditional on retaining a share in the future management of the racing’. Elements within government even queried how closely she was keeping her cards to her chest on the profitability of the course (HO 320/143, cover minute).

As a confidential Home Office Working Party also reported, ‘Any scheme for the preservation of the racecourse facilities at Aintree will inevitably entail public expenditure on a very large scale …’. Even before the Liverpool civic authority considered their final position, they would require sanction from ministers for a large loan and an Open Space grant under the Local Government Act (1966) for parks and recreational space to accompany any new housing development. Given the Treasury had agreed maximum expenditure on land purchase for public open space of £3 million, such a sanction would be impossible: ‘The expenditure would be equivalent to building and laying out an industrial estate of 10 or more factories in a development area’ (PREM 13/3290, pp. 30-5).

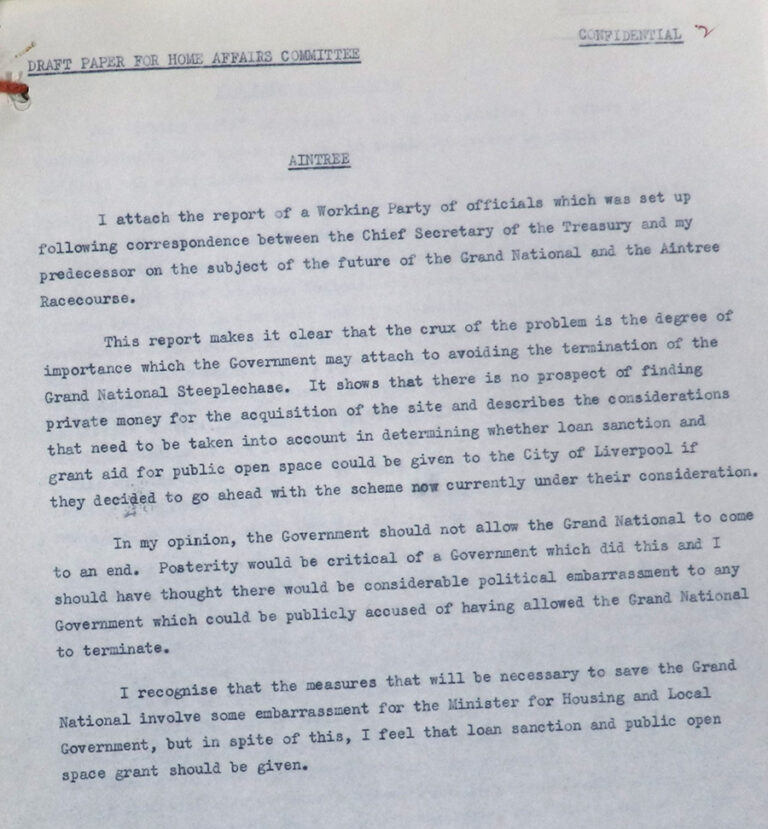

The same report, submitted in 1968, argued it was clear the race itself could only be saved with substantial public expenditure. Without investment in Aintree the race, which could not be run elsewhere on grounds of its unique history and character, would be lost: ‘Ministers will therefore need to decide whether the preservation of the Grand National has sufficient priority to justify the public expenditure in light of the stringent economies now in force’. The agonising decision was neatly expressed by one mandarin, who argued the importance of the race as ‘a major national sporting institution’ meant that:

‘the Government should not allow the Grand National to come to an end. Posterity would be critical of a Government which did this and I should have thought there would be considerable political embarrassment to any Government which could publicly be accused of having allowed the Grand National to terminate.’

No decisions had indeed been made by the time of the 1970 General Election of 18 June 1970. The day before, Wilson received news that Liverpool City Council would announce the breakdown of their negotiations with Mrs Topham due to the difference between her ‘hope value’ of £2 million and the Government-sanctioned offer of £1.25 million. Three weeks previously, Topham had again written to Harold Wilson to press her case and exploit the tense pre-election atmosphere to her own ends:

‘Believe me, the delay of four years is certainly not of my making and I have personally forfeited much in the hope that a reasonable and amicable solution might be reached.’

PREM 13/3290, pp. 11-12, 31 May 1970

Heath’s victory meant that Wilson would not be able to test the theory of Lord Wigg, now Chair of the Horseracing Levy Board, that her threat to racing at Aintree was ‘no more than bluff’ (PREM 13/3290, pp. 1-2).

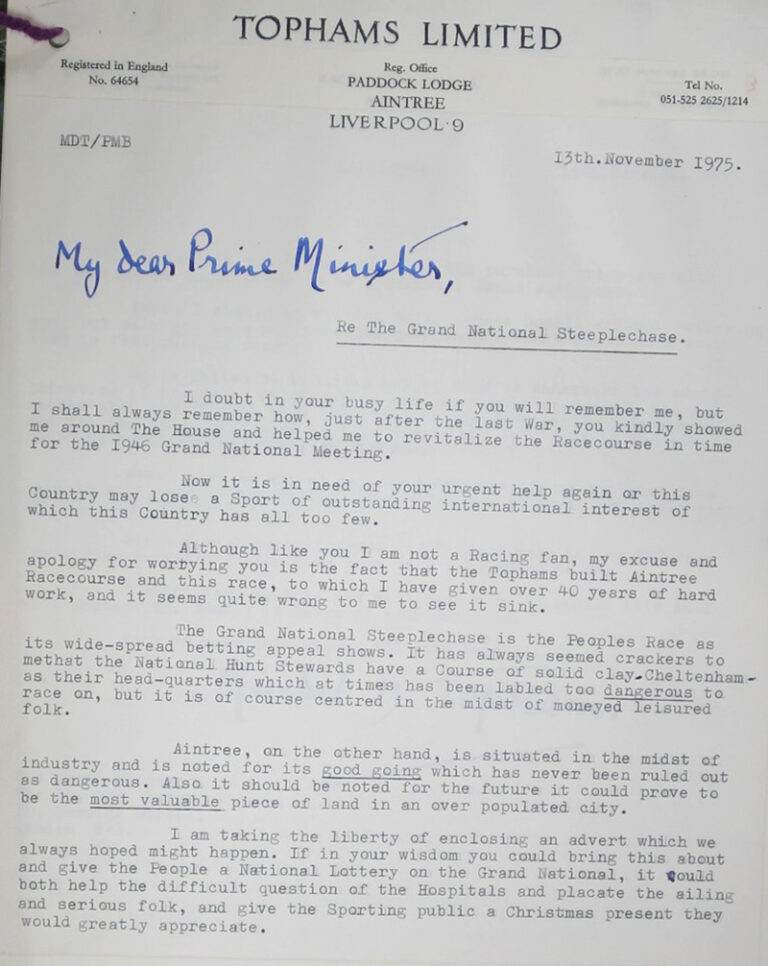

Within two years though, Mirabel Topham had proved she should never be underestimated. In 1972 she negotiated the sale (without planning permission) of Aintree racecourse to the Walton Group, led by local property magnate William Davies, for an astronomical £3 million. This fuelled several more years of wrangling within government over the future of the Grand National as Davies tried to liquidate his asset (footnote 6). Responding to shoestring plans for United Racecourses, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Levy Board, to run the 1976 race, Topham wrote to Wilson on 13 November 1975 to bemoan (without a hint of smugness) the potential loss of ‘a Sport of outstanding international interest of which this Country has all too few’. She concluded, impassioned:

‘Although like you I am not a Racing fan, my excuse and apology for worrying you is the fact that the Tophams built Aintree Racecourse and this race, to which I have given over 40 years of hard work, and it seems quite wrong to me to see it sink. … The Grand National is the Peoples Race as its wide-spread betting appeal shows. … Without wishing to intrude (United Racecourses staff not having a handle on the “101 things” that need doing around the course and in preparation), if I could help in any Honorary Consulting Capacity I should be more than pleased to do so.’

Throughout her relationship with the Grand National, Mirabel Topham combined tough, combative negotiating skills with a hard work ethic and immense humour and personality to ensure its survival. Even in her late seventies, she remained devoted to the great race. While her attitude towards Aintree itself might have been ambivalent and her unbendable commitment to the most challenging and controversial aspects of the race, those millions of people who will tune in this year owe her a considerable debt in ensuring the National remains the people’s race.

Footnotes

- www.theguardian.com/sport/2005/mar/23/horseracing.grandnational2005

- Files consulted for this blog are as follows: HLG 131/615 (1966-8); HO 286/5 (1954-9); HO 320/143 (1966-73); HO 320/144 (1965); PREM 13/3290 (1966-70); PREM 16/697 (1975); T 227/3119 (1968-70)

- Joan A Rimmer, ‘Aintree’s Queen Bee: Mirabel Topham and the Grand National’ (London, 2007)

- A handwritten note by Wilson reveals that the chair of the Planning Committee was his former Constituency Labour Party chairman and full-time agent

- Hansard: hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1968-07-02/debates/7cec1299-1d4b-4ee0-b730-6aa9245e9494/Aintree(GrandNationalSteeplechase)

- Fully detailed in PREM 16/697 (1975)

Fantastic story! I have personally been involved with Aintree Racecourse since the late seventies, with a slightly different type of horsepower….motorsport.

Interestingly there is no mention of the fact that the British Grand Prix was held at Aintree no less than five times (with record crowds of circa 150 000)…as well as Aintree being the UK’s only purpose built Grand Prix track….and it still remains…this year being it’s 70th anniversary.

Mirabel Topham was also our Club President, until her death in 1981.

Michael Ashcroft – Chairman, Aintree Circuit Club