One hundred years ago, the Law of Property Act (1922) brought to an end a system of manorial land rights which predated the Norman Conquest and is documented, already fully formed, in the Domesday Book.

Seven hundred years ago, what is today King’s Manor in the centre of York was the house of the Abbot of St Mary’s – an abbey to rival neighbouring York Minster and the holder of the lordship of numerous manors in Yorkshire.

What do these facts have to do with data and hackers? This year we celebrate the completion of the Manorial Documents Register (MDR) as a database: documents from counties across England and Wales have been pored over by specialists and this extraordinary record of manors and their surviving evidence is now searchable across every historic county. These documents are precious windows to the medieval world. But as windows they … often need a bit of a wipe. They are generally written in very difficult hands in languages most of us cannot understand. It is digital methods – sitting on top of centuries of scholarship – that can allow non-experts to access and make sense of these documents and what they tell us about medieval lives. And for scholars, digital techniques can build up impressions and analysis covering medieval ‘big data’ – more than be examined by hand – or by identifying new links and connections for study.

And so a hack weekend. In a manor. Using data from the MDR and some of the many digital projects that have been produced in recent years with the Middle Ages as their focus.

As organisers, we provided two main things alongside this evocative venue. The first was a significant amount of historical context: we started the day by hearing from Dr John Lee and Professor Sarah Rees Jones of the University of York who performed the seriously impressive feat of explaining both the manorial system and the documents it produced but also the approaches to their study, right up to the most recent scholarship. Combined with a display and presentation of documents from Laura Yeoman of the Borthwick Institute, participants came away with a really strong sense of the opportunities and challenges of manorial research.

The second thing we provided was a large quantity of datasets relating to the medieval period – a mix of manorial and wider material. Provision and accessible documentation of historical datasets promotes exploration, ideation and facilitates concrete discussions about approaches – even if those approaches are then applied to quite different data altogether.

A lot of interdisciplinary conversation between genealogists, archaeologists, computer scientists, archivists and historians then ensued. Attendees were interested in topics from coastal erosion and climate change, hedges, villages and villages sites through time to bioinformatics and health, data visualisation and networks. From all of these discussions and ideas, let me pull out, as our judges did, the winning ‘hacks’ from the weekend.

‘Manor Me This’ was an attempt by Jenni Lane to tackle some of these complexities head on. Jenni built a prototype for a website allowing researchers to look up common phrases, symbols and words that occur frequently in manorial documents. She also envisaged researchers working together as a community to resolve particularly sticky palaeographical challenges – and indeed you will often see researchers doing this on social media if they are struggling with particularly difficult writing.

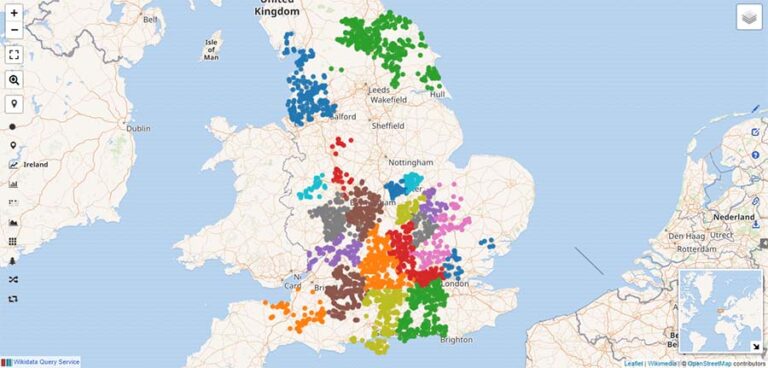

James Heald demonstrated some of the progress he had made in enriching the information about manors held in Wikidata. James has worked with us in the past to bring the Manorial Document Register wholesale into Wikidata. Why would anyone want to do this? Wikidata is a big and central database of many kinds of objects, identifiers and properties. Usually, in cultural heritage, when we produce exciting digital projects we focus on one kind of object, whether it’s a certain kind of document, group of individuals or piece of data. But Wikidata can bring all these together and query them all at once. This means we can use Wikidata to build up an increasingly rich picture of where manors are, who owns them through time and the documents they feature in. James used semi-automated matching and SPARQL queries to first match thousands of manors with references in Victoria County History volumes and then to visualise those matches and he hopes to continue with this sort of data enrichment.

Our very worthy winners (‘Team Baston’) took a very different approach, giving the judges a deep dive into a single manor in Kent while demonstrating methods which could be used for many manorial holdings.

They first used the interactive fiction tool Twine to present an interactive journey around a manor based partly on documents relating to Baston Manor in Kent and partly filling in illustrative, contextual information from other representative manorial examples. The results, even from a prototype, were informative, entertaining and immersive. Not content with one sort of virtual representation of a manor, however, the team also produced a second.

Manors are notoriously difficult to map. Their boundaries are not necessarily in one piece – they may be in several unconnected sections – and they may be quite idiosyncratically described. My colleagues and I spent a small part of the weekend trying to match a 17th-century perambulation describing a manor’s boundaries to modern digital maps of the same area. We failed. (Not just a bit, I should say, but almost entirely!)

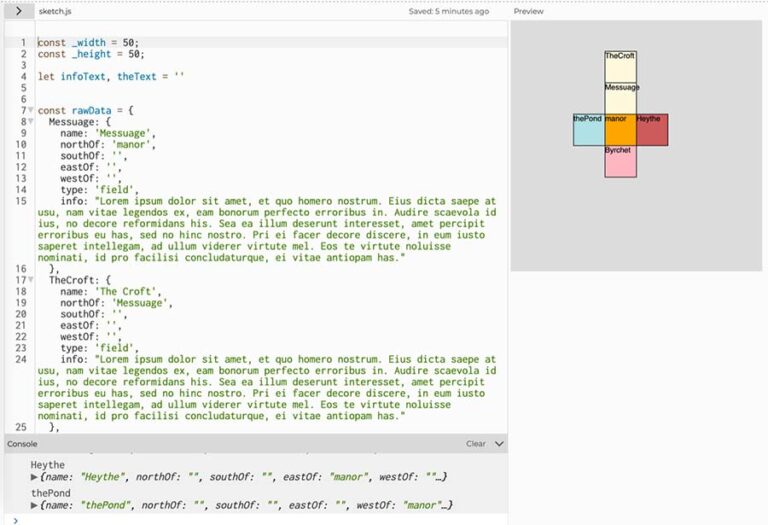

Team Baston decided to create schematic maps. They did this by extracting data from manorial documents to a spreadsheet layer which they then used the p5.js library to visualise. In the past, large-scale funded projects such as ChartEx have used natural language processing to attempt to reconstruct holdings which are often described in complex, referential relationships to each other (‘the bishop’s estate lies south of the field belonging to the Widow Smith’, ‘the Widow Smith’s land is west of the church and south of the land belonging to John the Miller’). For the team to produce results in a weekend was very impressive, even with significant human intervention.

I want to thank everyone who attended this event but particularly our hosts at the Centre for Medieval Studies, our expert speakers and judges and the staff of the Borthwick Institute, York Festival of Ideas and our sponsors at Wikimedia UK.

Would we run something like this again? You bet. It was amazing to see the exchange of ideas and creativity from the participants and hopefully many of their ideas and projects will have a life beyond the weekend.

‘Twas fun. Sorry not to be able to stay for more of it. Results look really impressive. Please do it again.

I’ve only had a short play with the MDR for Cheshire, partly because it’s not been out that long. The big issue for me as a family historian is that it appears to be easy enough to search by the name of the manor, but if you don’t know what manor covered the town or village that you’re interested in, it may take an age of guessing to find anything relevant. Even then, you might not know if you’re missing something else for that parish that happens to be in another manor. One of the ideas above would seem to perhaps link the outside world to the world of the manors. Cross fingers…

Update: it is possible to search by parish. However, if I understand things correctly, the manor has only one parish linked with it – that where the demesne was located, ie where the lord of the manor lived if he was there. This means that if a manor spreads across 2 parishes, with the holdings in a second parish being split, if you search on the parish containing 2 manors, the “home” manor plus the spreading manor, you’ll find the “home” manor, but not the interloper, so to speak.