Event: Friday 18 May 2018, 18:30

Event: Friday 18 May 2018, 18:30

Suffrage 100 – Archives at night: Law breakers, law makers

Visit our Suffrage 100 web portal for more information on events, records and resources.

Today marks a significant moment: the unveiling of the first statue of a woman in Parliament Square.

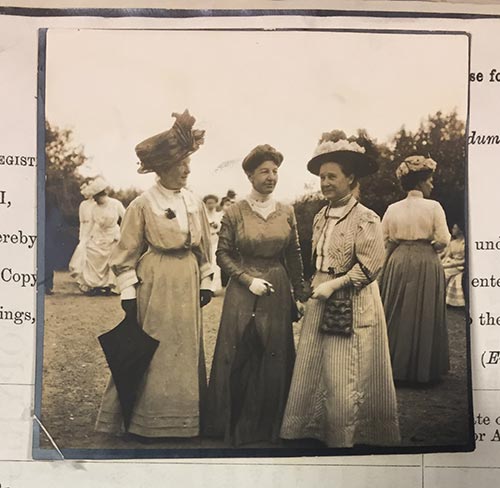

COPY 1/538/1 Photograph from August 1909 of Miss Garrett, Mrs Frank Dawes & Mrs Henry Fawcett.

This moment is important for a number of reasons. Firstly, just over 100 years ago, in this space outside Parliament, peaceful protests and violent clashes with the police took place: regular conflicts between suffrage supporters and the state.

Secondly, the woman in question is Millicent Fawcett, the fearless leader of the constitutional and democratic National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), often known as the Suffragists. In 100 years women have gone from having no right to vote in parliamentary elections to being publically commemorated for their role in the movement for women’s enfranchisement.

Government bias towards the militant movement

On a simplistic level, looking at The National Archives’ records you could be forgiven for thinking that the women’s suffrage movement started with the outbreak of militant activity in 1905. However, there were rich, constitutional campaigns for the 50 years proceeding this point, and indeed after it. Both suffragists and suffragettes – the traditionally militant campaigners – used constitutional methods, including marches, demonstrations, petitions and the lobbying of politicians.

In many ways, the records in our collections signify the huge frustrations the constitutional campaigners must have felt; despite all their years of active campaigning, the government was seemingly not listening to peaceful protests.

Despite this, some fascinating records can be found in The National Archives about constitutional campaigns, although they are often less obvious in the collections of a government archive – a government seemingly far more concerned by militancy, than by petitions or peaceful protests.

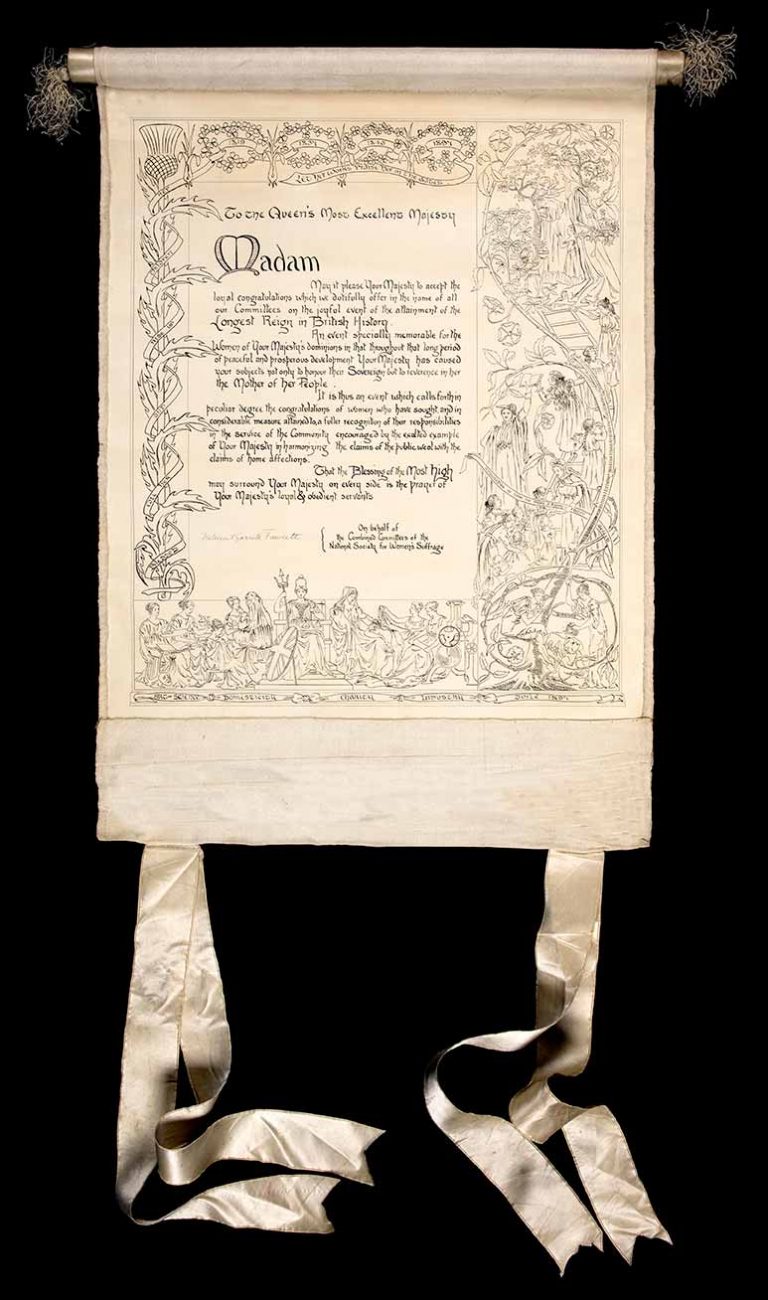

PP 1/349/2 National Society for Women’s Suffrage address to Queen Victoria on her Diamond Jubilee. Mounted on silk; pen and ink illustrations. 1897.

Millicent Fawcett

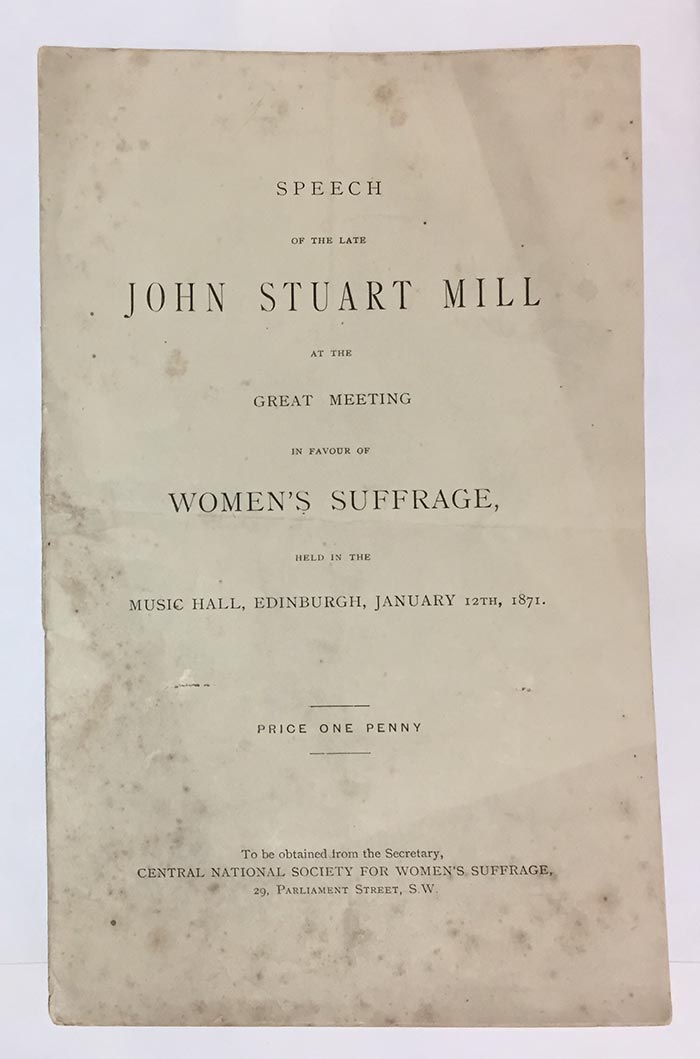

PRO 30/69/1834 – Transcript of speech made by the Liberal MP and political thinker John Stuart Mill on women’s suffrage, 1871

Millicent Fawcett was a true leader and pioneer of the movement for women’s suffrage. Historically she has often been overshadowed by the prominent Pankhurst family, who founded the Women’s Social and Political Union, and their more striking, militant methods. Constitutional, non-militant campaigns spanned the decades prior to the WSPU’s formation in 1903, with little success and an increasing sense of frustration.

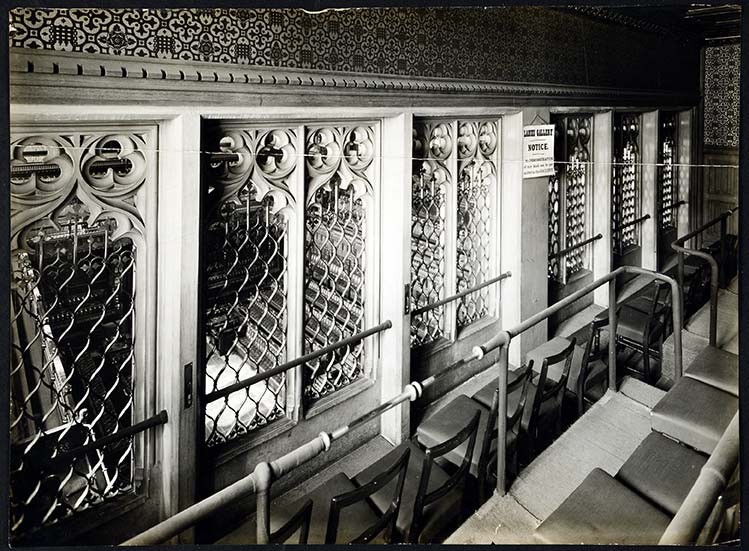

Born in 1847, Millicent Garrett Fawcett was a member of a family of women’s rights pioneers. From 1866, although supposedly too young to sign herself, Fawcett helped organise signatures for the first petition for women’s suffrage. John Stewart Mill agreed to present the petition to Parliament, provided it could get at least 100 signatures, it eventually gathered 1,499. Through their friendship she met Henry Fawcett, a Liberal Member of Parliament, and they soon married. Henry had been blinded in a shooting accident in 1858 and Millicent often acted as the eyes of her husband in Parliament, regularly attending the Ladies’ Gallery to listen to debates in the House of Commons. The Ladies’ Gallery presented a very literal barrier to women participating in Parliament: a stout iron grille.

WORK 11/176 – Photograph of the House of Commons Ladies’ Gallery, 1888-1908

National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies

Fawcett was involved with numerous suffrage societies before later becoming president of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) in 1907, an umbrella organisation for all the suffrage societies in England, Scotland, and Ireland.

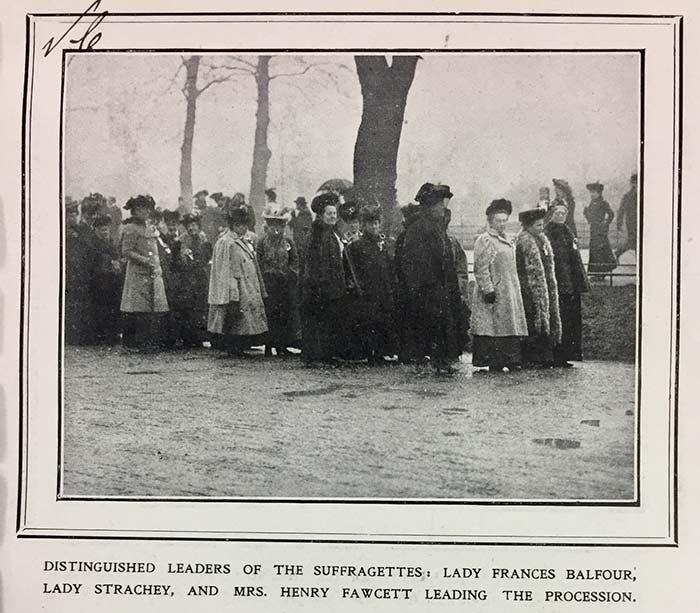

On 9 February 1907 she was one of the leaders of the infamous ‘mud march’, or United Procession of Women, organised by the NUWSS to coincide with the opening of Parliament. This peaceful march was the largest suffrage demonstration to date and attracted significant press attention for the cause. In defiance of the rain and muddy conditions, several thousand women marched, and arguably this a gave the march even greater media impact. Despite the powerful protest, once again the resulting vote was talked out of parliamentary time.

ZPER 34/130 – Key figures leading the 1907 ‘Mud March’ protest

This was just one of many impactful protests lead by the NUWSS. Large-scale, peaceful demonstrations became a key campaigning method.

At the 1911 Coronation procession, Suffragists and Suffragettes stood shoulder to shoulder, in a suffrage demonstration thought to number about 60,000 participants.

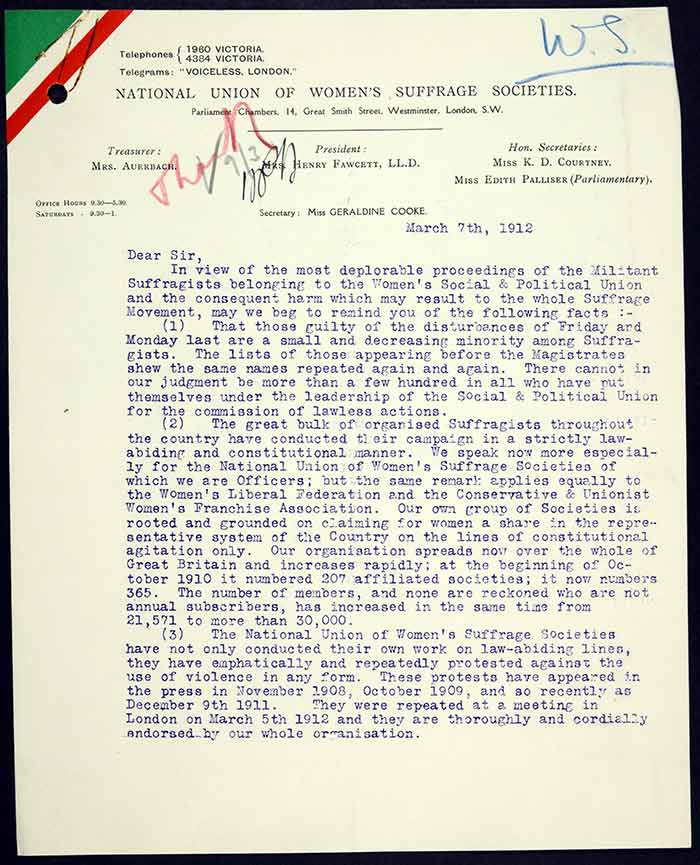

The relationship between the NUWSS and WSPU was complex, and history has often pitted these organisations as opponents. Cross-membership of suffrage societies was common; however, there were also tensions. After the mass window smashing campaigns of March 1912, which saw shops across London’s West End targeted in attempt to sway government opinion, Millicent Fawcett wrote to the government to condemn these actions of a ‘small and decreasing minority’. On 1 March it was said that approximately 150 women smashed windows simultaneously across the capital – and this was only day one of the campaign. Fawcett felt that this risked harming the suffrage movement as a whole.

T 172/968B – Letter protesting about militant methods used by members of the WSPU in March 1912

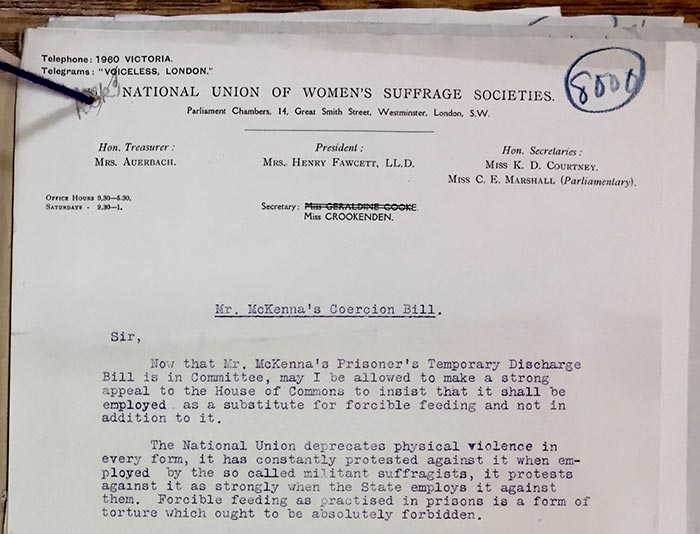

Despite this condemnation, the NUWSS was also one of many societies to fiercely protest against the use of force feeding by the government, seeing it as ‘physical violence’ – which they deplored whether it was instigated by Suffragettes or by the government. They wrote letters of formal protest, including on the introduction of the 1913 Cat and Mouse Act, or Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act, which enabled the government to release individuals on health grounds and then later re-arrest them.

The National Union deprecates physical violence in every form, it has constantly protested against it when employed by the so called militant suffragists, it protests against it as strongly when the State employs it against them.

T 172/968B – Letter protesting about the violent force-feeding of suffragette prisoners, 1913

One of the NUWSS’s most effective protests was that of the 1913 Suffrage Pilgrimage, a national pilgrimage designed to reach women all over the country.

During the six-week pilgrimage they held a series of meetings all over Britain where they sold The Common Cause and other suffrage literature. The meetings held on the way were nearly all peaceful. However, reports in Home Office files show that these meetings were not without problems: demonstrators were often met by hostile crowds, heckled or had items thrown at them. On 15 August 1913, NUWSS sent a submission to the Home Office on the Report of Provision for Maintenance to highlight problems they faced in the policing of such gatherings on the pilgrimage.

At the outbreak of war in 1914 the NUWSS continued their campaigns – unlike the WSPU, who suspended their militancy and campaigns.

ZPER 34/143 – Images from the great suffrage pilgrimage and its final gathering in Hyde Park

A partial victory

The Representation of the People Act was finally passed in 1918, increased voting rights by abolishing practically all property qualifications for men and by enfranchising women over 30 who met minimum property qualifications. The vote has often been seen as a reward for women’s contribution to the war effort; however, many of the women working in the First World War would not have met these qualifications.

In 1928 equal franchise was finally won, under the Representation of the People Act (1928), which extended the vote to all women over 21 years of age. Emmeline Pankhurst died just weeks before on 14 June of that year. Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS, was still alive and attended the parliamentary session to see the vote take place. The Act added 5 million more women to the electoral roll, making women the majority of the electorate in the 1929 general election.

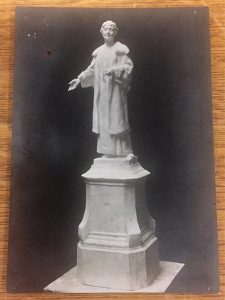

Emmeline was commemorated a year later with a statue in London’s Victoria Tower Gardens, on which we also hold records. It was unveiled in 1930 by the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, who had opposed votes for women.

- WORK 20/188 – Photograph of Emmeline Pankhurst’s statue, Victoria Tower Gardens

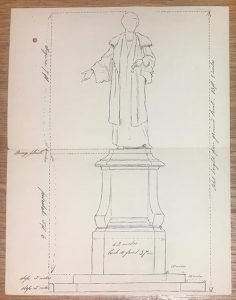

- WORK 20/188 – Drawing of Emmeline Pankhurst’s statue, Victoria Tower Gardens

It was the militant campaigner, who had led so many window smashing campaigns on government buildings, who was the first to be commemorated with a statue outside Parliament. Once again, it was the WSPU’s striking campaigns, vivid colours and media image that captured the public’s attention in the memorialisation of the women’s suffrage movement.

Eighty-eight years later Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the constitutional campaigns, is finally being recognised in Parliament Square. She was the leader of the largest suffrage society, and arguably the leader of the suffrage society that had the biggest impact on women wining the vote. What do you think?

The Fawcett archives are held at The Women’s Library at the Library of the London School of Economics, ref 7MGF.

It is simply not true that the Government had a bias against women getting the vote, they decided men couldn’t have it in most cases and in the cases of Conscientious Objectors they didn’t get the vote. As you have said the Suffragettes were met by hostile crowds (including women) who were against the Suffragettes and disapproved of what they claimed they were trying to do. It is very easy to claim Government bias but in view of the violence the Government had the right to protect the country, let’s not forget it wasn’t just window smashing, but chemicals in the post, explosions and burning down of buildings let alone attacks on individuals and the only surprise is that some of the more violent Suffragettes should maybe have been sent to Asylums rather than prison. I don’t see how women made up the majority of the electorate in the 1929 Election (even given the men who had been killed during the First World War), where is the evidence for this.

Hello David,

Thank you for your continued interest in our blogs.

F W S Craig’s book on British Electoral Facts, 1885-1975 provides a breakdown of electorate statistics for the 1929 election. These were statistics compiled by the Registrar-General which broke down the electorate by sex (which stopped after 1938).

The statistics show that the total electorate for the 1929 election was recorded as 28,851,359. Of this number 15,193,925 were women. 13,657,434 were men. This calculates that women made up 52.7% of the electorate against 47.3% of men.

Craig’s book is available in our Library collection. http://tna.koha-ptfs.co.uk/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=35341&query_desc=kw%2Cwrdl%3A%20British%20electoral%20facts

Obviously this is just one of the available sources for researchers to consult but this should clarify that women did make up over 50% of the electorate in 1929, following the passing of equal franchise the year before.

Thanks again

David Langrish

Head of the Public History team

[…] an interesting post about the women’s suffrage movement in the UK (with primary source […]