The Treaty of Versailles, signed with Germany on 28 June 1919, brought an official end to the war between Germany and the Allied and Associated Powers, but it did not bring an end to the peace negotiations. There were still treaties to be signed with Germany’s partners who had formed the Central Powers in the First World War: Austria, Hungary, Turkey and Bulgaria. The first of these was to be Austria.

Paris Peace Conference

On 2 June 1919, with the Paris Peace Conference ongoing, the Allies presented peace terms to the Austrian delegation, led by Austrian Chancellor Karl Renner. The Austrians put forward counter-proposals, and after three months of negotiation and a further draft, a third and final proposal was submitted to the Austrian delegation on 2 September 1919. The covering note, by Georges Clemenceau, the French Prime Minister, contained an ultimatum that the Austrian Assembly should approve it within five days. On 6 September 1919 the Austrian National Assembly formally accepted the terms of the treaty, although under considerable protest (FO 608/23/1).

The Treaty of St. Germain-en-Laye

Austria: Treaty of Peace, also known as the Treaty of St. Germain-en-Laye

The Treaty of St. Germain-en-Laye was finally signed on 10 September 1919 in the great hall of the ‘Chateau Neuf’ in St. Germain-en-Laye, by Austria and the Allied and Associated Powers. The British delegation consisted of Arthur James Balfour, Foreign Secretary, Andrew Bonar Law, Privy Seal, Viscount Milner, Colonial Secretary, and George Nicholl Barnes MP, Minister without Portfolio (FO 93/11/74).

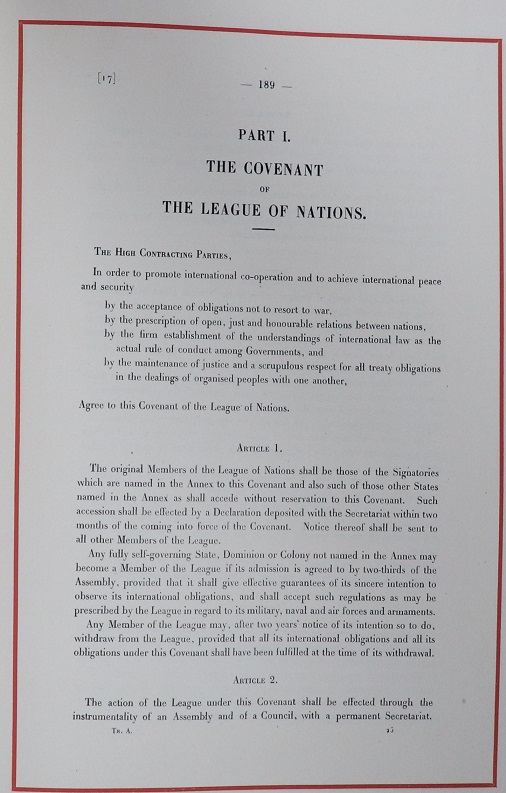

The treaty covers 381 articles divided into 14 parts, and is written in French, English and Italian. As with the peace treaty with Germany, the Treaty of Versailles, the first part starts with the covenant establishing the League of Nations. For this reason the United States did not sign, but established their own treaty – the US-Austrian Peace Treaty – in 1921.

Part I: The Covenant of the League of Nations. Catalogue reference: FO 93/11/74

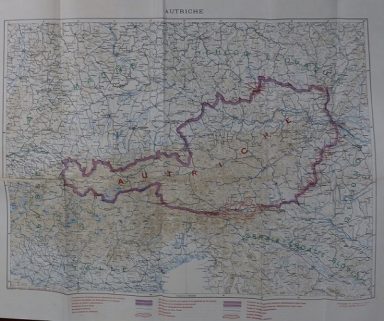

The second part (articles 27–55) covers the frontiers of Austria, with clauses covering Switzerland and Lichtenstein, Italy, Klagenfurt, the Serb-Croat-Slovene State, Hungary, the Czecho-Slovak State and Germany. The clauses establish fixed boundaries, to be enforced by a boundary commission, tasked with laying out those frontiers on the ground. Austrian territory was reduced to the borders of Austria alone, which effectively left it at around 40% of its previous size.

Boundaries of Austria by the Treaty of St. Germain-en-Laye, 10 September 1919, showing old boundaries and plebiscite area. Catalogue reference: FO 925/20026

Part three (articles 36–94) deals with political clauses for Europe, which are largely questions of nationality and land ownership beyond the former Austro-Hungarian frontier. Austria was to renounce further territory in favour of Italy, the Serb-Croat-Slovene State, the Czechoslovak State and Romania.

Part four (articles 95–117) involves Austrian interests outside Europe, whereby Austria was to renounce trading rights, titles and privileges gained in earlier treaties with Morocco, Egypt, Siam and China.

The fifth part (articles 118–159) tackles military, naval and air clauses, starting with the demobilisation of Austrian forces and the abolition of compulsory military service. The Austrian Army was to be limited to 30,000 troops to be limited exclusively to the maintenance of order and to border control. The manufacture of arms and munitions was to be limited to one state-owned factory, with a ban on all imports and exports. All warships and submarines were to be surrendered and any that were in the course of construction were to be broken up. Air forces were to be abolished and the personnel demobilised within two months of the coming into force of the treaty. An Inter-Allied Commission of Control was to be established to ensure that the clauses were being met.

Part V: Military, naval and air clauses. Catalogue reference: FO 93/11/74

Part six (articles 160–172) concerns prisoners of war and war graves and part seven (articles 173–176) deals with the establishment of war crimes tribunals.

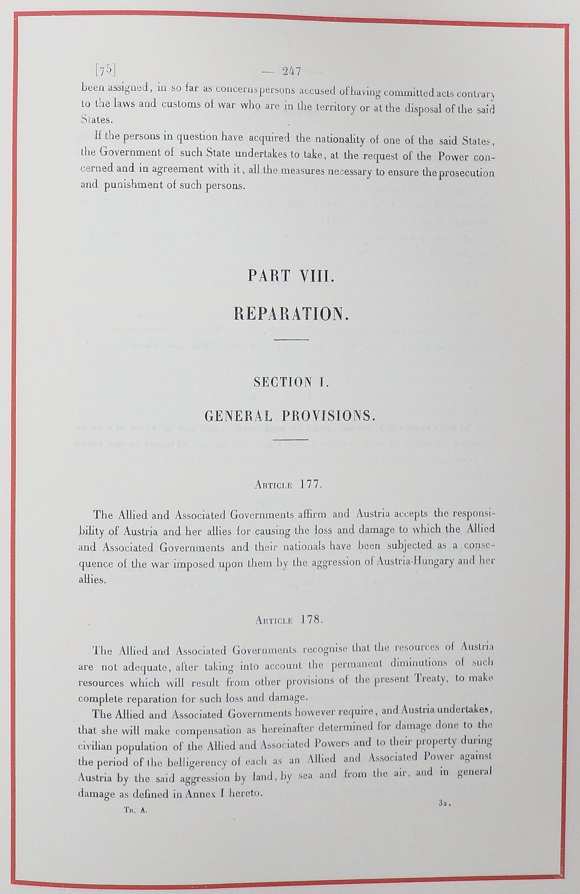

Parts eight to ten lay out the monetary costs of the war. Part eight (articles 177–196) covers reparations. In article 177 Austria is forced to accept responsibility, along with her allies, for the damage caused to the Allies in ‘the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Austria-Hungary and her allies’.

While acknowledging that a diminished Austria would not have the resources to make complete reparations for damage caused by the war, subsequent articles required Austria to make compensation for damage done to the civilian population and to their property, to an amount to be determined by a Reparation Commission. Where it was possible to identify, Austria was to provide for the restitution of cash, animals and objects, including records, documents, antiquities and art.

Part VIII: Reparation. Catalogue reference: FO 93/11/74

An annex in part eight names specific objects, many of which had been removed well before the First World War. Some of these included: the crown jewels of Tuscany, which were removed to Vienna during the 18th century; objects made in Palermo in the 12th century and used in the coronation of Holy Roman Emperors; the triptych of St Ildephonse by Rubens, taken from Brussels and removed to Vienna in 1777, and the gold cup of King Stanislas IV of Poland, removed some time after 1772.

Financial clauses (articles 197–216) required the Government of Austria to pay the total cost of the armies of occupation. There was to be a ban on the sale of gold and the Austro-Hungarian Bank was to go into immediate liquidation.

The economic clauses (articles 217–275) tackled commercial relations, duties and tariffs, largely aimed at ensuring favourable trading rights for Allied and Associated Powers countries.

The remaining articles cover civil aviation and freedom of navigation for ports, railways and waterways, telegraphs and communication and the organisation of labour.

The treaty ends with a stipulation that the single original copy would remain in the archives of the French Republic and that an authenticated copy would be transmitted to each of the signatory powers.

The copy deposited in The National Archives bears the signature of Stephen Pichon, the French Foreign Minister (FO 93/11/74).

The treaty marked the official end of the First World War for Austria and for the majority of the states and kingdoms comprising the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, with the exception of Hungary, who would sign their own peace treaty, the Treaty of Trianon, on 4 June 1920.

The treaty finally came into effect on 16 July 1920. Austria struggled to cope with the demands imposed by the Allies and the Austrian annexation, or ‘Anschluss’, by Nazi Germany in 1938 is widely regarded as a consequence of the military, financial and geographical restrictions.