On 3 November 1918, a delegation from the Austro-Hungarian Empire signed the terms of an armistice with representatives of the Italian Army. This was one of the closing acts in a war that had begun over four years earlier, as a result of German and Austrian aggression.

After costly campaigns – predominantly against the Serbs, Russians and Italians – defeat at the end of the war led to the dismantling of the Empire, a huge loss of territory and the creation of Austria and Hungary as separate states.

Austro-Hungarian Army prisoners captured by British troops on the Italian front. Catalogue reference: ZPER 34/154 Illustrated London News, January – June 1919

Background: the start of the war

In 1914, the Austro-Hungarian Empire comprised Austria, Hungary, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovakia, Slovenia, the Free State of Fiume, and parts of modern-day Poland, Ukraine, Italy, Serbia, Romania, Montenegro and the Czech Republic.

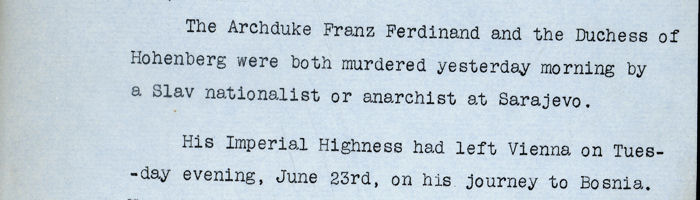

On 28 June 1914, Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria, and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia (FO 371/1899). Franz Ferdinand was the nephew of the ageing Emperor of Austria, Franz Joseph, and likely heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. The assassination set in train a whole set of diplomatic manoeuvres that were to become known as the July Crisis, each bringing the prospect of war ever closer.

Report from British Ambassador in Vienna regarding the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria on Monday 29 June 1914. Catalogue reference: FO 371/1899, folio 303

Austrian diplomats effectively accused the Serbian government of complicity in the assassination. A ten-point ultimatum was issued by Austria to Serbia on 23 July 1914. The terms of the ultimatum amounted to a loss of independent law making and sovereignty (FO 371/2158) – and, although Serbia agreed to most of the terms, on 28 July Austria-Hungary declared war on the small Balkan state (FO 371/2159).

Treaties, alliances and ententes drew together what would become the two opposing factions in the First World War: the Allied Powers and the Central Powers. On 1 August, both Austria-Hungary and Germany declared war on Russia (FO 371/ 2160). On 3 August, Germany declared war on France and on 4 August it invaded neutral Belgium. This forced the hand of the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, and sent Great Britain – and, by extension, the British Empire – into the horrors of the First World War (FO 371/2161).

Military engagements

The terms of Austria-Hungary’s military agreement with Germany required Austro-Hungarian forces to focus on protecting the German forces invading France against attacks from the Russians, at the expense of their campaign against Serbia. Although Austria-Hungary captured the Serbian capital Belgrade on 1 December 1914, the Serbs were able to retake the city, along with 40,000 Austrian prisoners. Austro-Hungarian forces did not take Belgrade again until 9 October 1915.

Austria-Hungary began an offensive against Russia in August 1914. Despite some initial success at Kraśnik and Komarow, they were eventually defeated at the Battle of Galicia. By November, the Russian Army had encircled the strategically important fort at Przemyśl. Rather than attack the fort, the Russians decided to simply wait for their food and ammunition to run dry. The siege of Przemyśl became the longest of the war. Relief efforts were unsuccessful, and the Austro-Hungarian surrender came in March 1915. Almost 130,000 men were taken prisoner by the Russians (WO 106/1122).

In the aftermath of Przemyśl, the Germans felt the need to ensure that Austria-Hungary continued to fight, while also deterring Italy and Romania from joining the Allies. They decided to attack Gorlice. Launched on 2 May 1915, the Gorlice-Tarnow offensive saw German and Austro-Hungarian forces secure a major victory. They soon gained over 110 miles and inflicted losses totalling 210,000 (including prisoners of war). The resulting Russian Great Retreat ensured that Russia avoided total defeat.

Italy’s entry into the war on the Entente side in May 1915 put further strain on Austria-Hungary. The Italians focused on attacking near the Isonzo River as a means of reaching Trieste and eventually threatening Vienna. Italian forces outnumbered their counterparts but, occupying the higher ground, Austro-Hungarian defences held firm.

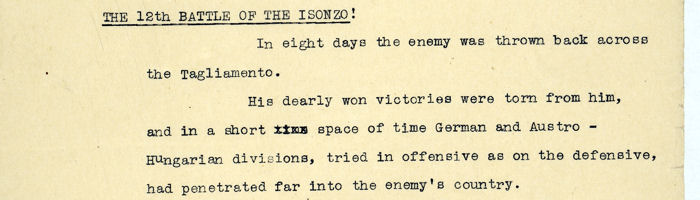

There was little movement on the Italian front until October 1917, when Austro-Hungarian and German forces launched the Battle of Caporetto (or Twelfth Battle of Isonzo) (WO 369/8/4). This was a great success, and pushed the Italians back to the Piave River.

Preface to translation of an Austrian account of the 12th Battle of the Isonzo. Catalogue reference: WO 106/847

Despite success at the Battle of Caporetto, the war continued to take its toll on Austria-Hungary. In May 1918, the head of the British mission to Italy, Sir Charles Delmé-Radcliffe, reported a very negative impression of the state of the Austro-Hungarian Army. In a note on 12 May, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir Henry Wilson, expressed surprise at Delmé-Radcliffe’s assessment; he noted that, if this were true, Germany would need to send further support for Austria-Hungary to the Italian front (WO 106/593).

The following month, Italy won a decisive victory at the Battle of the Piave River. Austro-Hungarian forces were finally defeated at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto in October (CAB 25/99), leading to the rapid recapture of the cities of Trento and Udine, and opening the way to Trieste. With the Italians now at the Austrian border, and following independence declarations from the nascent nations of Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia (or the state of the Slovaks, Slovenes and Serbs), the Austro-Hungarian Government had little option except to surrender and call for peace (CAB 24/69/56).

Armistice

On 30 October, Austrian General Viktor Weber Edler von Webenau and a small peace contingent approached the Italian trenches, carrying a white flag. The following day the party were driven to a large country house: the Villa Giusti, on the outskirts of Padua, close to the headquarters of General Diaz, Commander-in-Chief of the Italian Army. On 1 November, telegrams were exchanged between Allied headquarters at Versailles and the Villa Giusti, outlining the conditions for accepting an armistice.

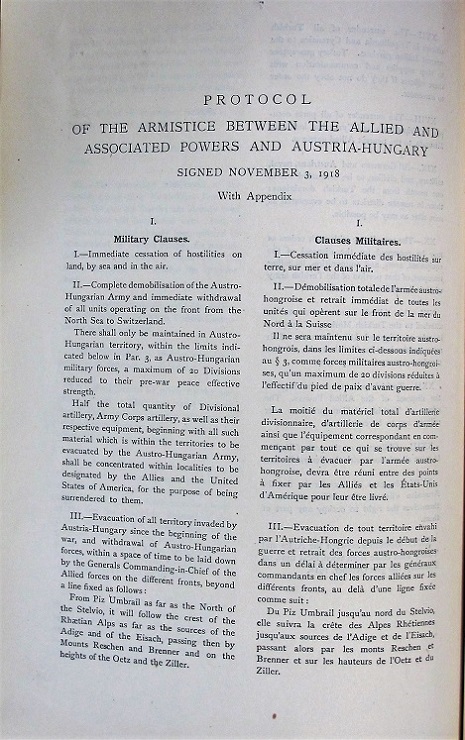

Terms of the armistice signed between the Allied and Associated powers and Austria-Hungary.

Catalogue reference: ADM 116/1931

The armistice was signed at 15:00 on 3 November 1918 by General Weber, as head of the Austro-Hungarian armistice commission, along with six officers of the Austro-Hungarian Army. On the Italian side the chief signatory was Lieutenant General Pietro Badoglio, Chief of Staff of the Italian Army, along with six subordinate officers.

Under the terms of the armistice of Villa Giusti, all hostilities were to cease 24 hours after the signing. The Austro-Hungarian Army were to withdraw immediately from all occupied territory, as well as ceding areas disputed with Italy, such as Trieste and Dalmatia. The armies held on Austro-Hungarian soil were to be limited to a maximum of 20 Divisions. In addition, all German troops within occupied and Austro-Hungarian territories were to evacuate within 15 days, and those troops who had not left within that time would be interned.

Allied armies were also to be granted freedom of movement within Austria-Hungary. This allowed easy access to the German border. Allied nations were to be allowed freedom of navigation of the Danube, and the naval blockade imposed by the Allies was to continue.

Under further terms, Austria-Hungary had to surrender all submarines in their control, as well as battleships, light-cruisers and destroyers; the remaining fleet was to be returned to shore and disarmed. All war and railway materials in the areas to be evacuated were to be left behind and all supplies had to be surrendered, including coal. The armistice also called for the immediate repatriation of all prisoners of war, internees and displaced persons, and the restitution of all merchant vessels detained by Austria-Hungary (ADM 116/1931).

Aftermath

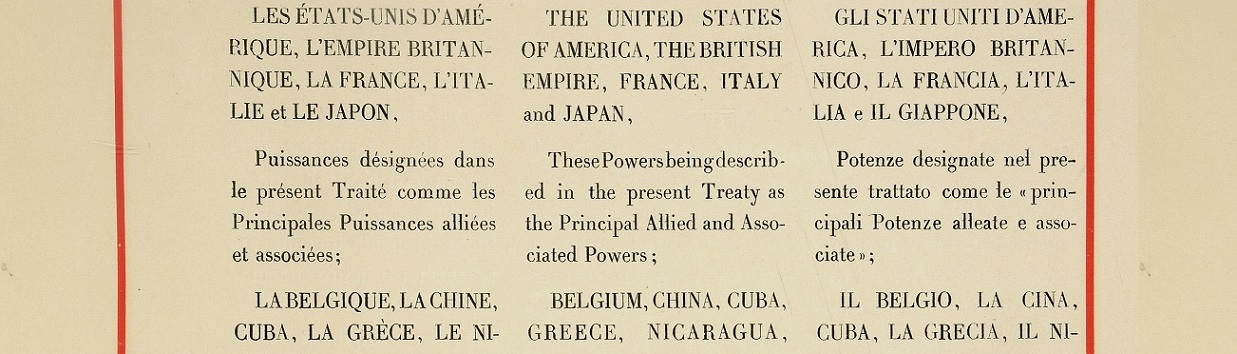

The Treaty of Saint Germain-en-Laye. Catalogue reference: FO 93/11/74

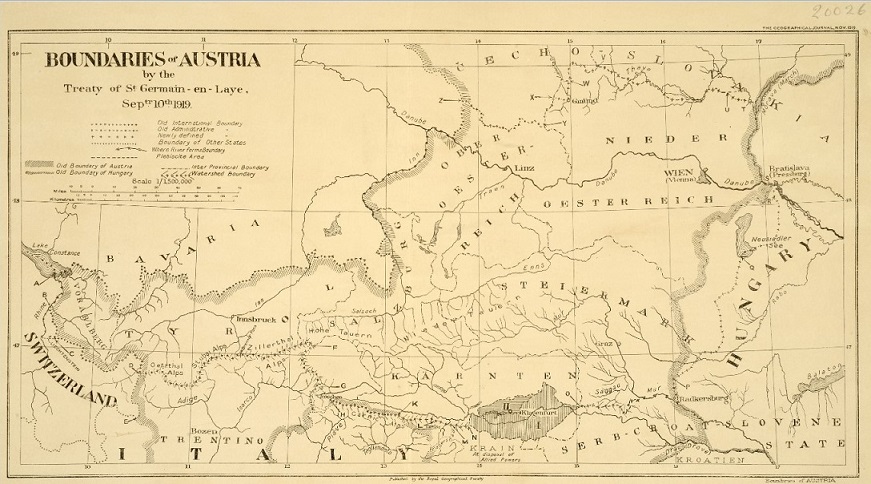

On 10 September 1919, Austria signed the Treaty of St Germain-en-Laye. Under the terms of the treaty, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was dissolved and Austrian territory was reduced to the borders of Austria alone: this effectively left it at around 40% of its previous size. Much of its empire was subsumed within Czechoslovakia, Poland and Yugoslavia.

Boundaries of Austria by the Treaty of St Germain-en-Laye, 10 September 1919.

Catalogue reference: FO 925/20026

Additionally, the Austro-Hungarian army, navy, and air force were disbanded, and a reconstituted Austrian Army was limited to 30,000 troops. Financial ‘reparations’ were imposed upon Austria for war damages incurred by Allied countries, and favourable trading and navigation rights within Austria were also granted to the Allies (FO 93/11/74).

Austria struggled to cope with the demands imposed by the Allies: the Austrian annexation (or Anschluss) by Nazi Germany in 1938 is widely regarded as a consequence of the military, financial and geographical restrictions imposed under the Treaty of St Germain-en-Laye.

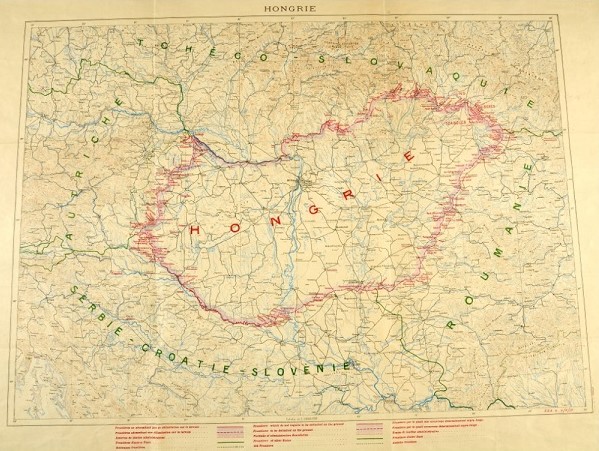

A separate treaty, the Treaty of Trianon, was signed with Hungary. In addition to limiting the Hungarian Army to 35,000 troops, and imposing financial reparations, Hungary lost over 70% of its pre-war territory – mostly to Romania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. (FO 93/122/1).

Borders of Hungary under the Treaty of Trianon, 4 June 1920. Catalogue reference: FO 925/20046

Look out for our last blog post in the series Milestones to Peace, which will be published on 11 November, to coincide with the armistice signed by Germany.

We are also hosting a variety of activities to mark the anniversary of the Armistice with Germany and the end of our centenary programme, First World War 100.

All of the armistices and treaties will be shown together for the first time during the conference ‘Peace making after the First World War’ taking place from Thursday 27 to Friday 28 June 2019.

Why did Austria in panic go back to her designated border. Italy gained lots of Austrian prisoners without a fight.?????