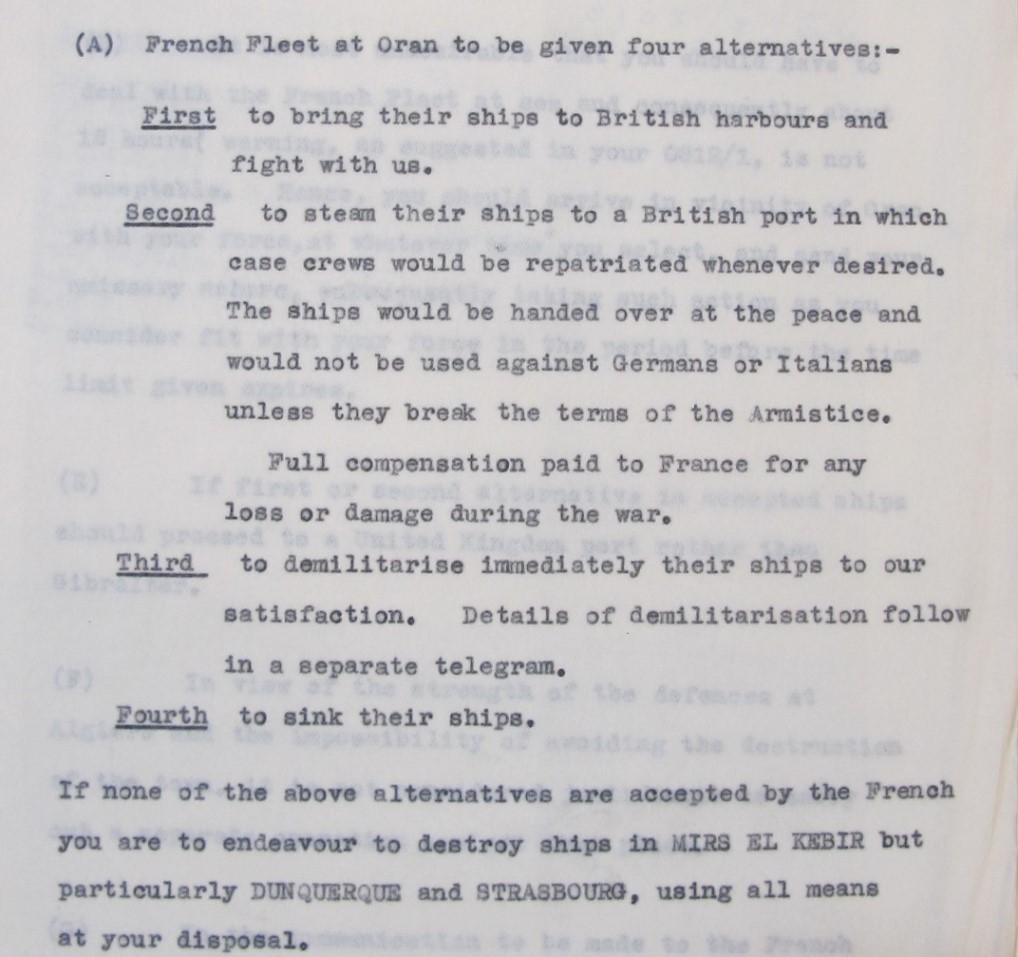

Mers-el-Kébir. Three words that signify the nadir of 20th century Anglo-French relations. In the early evening of 3 July 1940 the British warships of Vice-Admiral James Somerville’s Force H opened fire on the virtually defenceless vessels of their former ally, France. In the space of nine minutes the British destroyed or disabled much of the French fleet and killing almost 1,300 French sailors.

For many across the Channel the events of 3 July 1940 represent the ultimate betrayal of trust by a close ally. The decision taken by Winston Churchill to sink the French fleet rather than let it fall into the hands of the Germans is one that has been discussed at great length ever since that summer evening. What no one, until now, realised is that this was not the first time Churchill had been faced with this problem.

- Winston Churchill prior to his appointment as First Lord of the Admiralty 1910

- Winston Churchill in 1940 (catalogue reference: CN 11/6)

The summer of 1940 had proved disastrous for the Anglo-French alliance. Stunning German military successes had left the French army in ruins, and the French government was forced to sign an armistice on 22 June. Article 8 of the armistice agreement concerned the French fleet. It stated that the fleet was ‘to collect in ports to be specified, and under German and/or Italian control to demobilize and lay up’.

The German government declared that the French fleet would not be used for war, but this held few comforts for the British. At the end of June 1940 the Chiefs of Staff Committee produced a memorandum in which they declared that:

In the light of recent events we can no longer place any faith in French assurances, nor could we be certain that any measures which we were given to understand the French would take to render their ships unserviceable before reaching French metropolitan ports, would in fact be taken. Once the ships have reached French metropolitan ports we are under no illusions as to the certainty that, sooner or later, the Germans will employ them against us. (CAB 80/14)

As such they recommended that the French fleet be forced to choose between internment in a British or neutral port, or destruction by the Royal Navy. This position was accepted by Churchill and the Cabinet in a meeting in the afternoon of 1 July 1940 (CAB 65/14/1). Churchill would later write that ‘this was a hateful decision, the most unnatural and painful in which I have ever been concerned’.[ref]1. Winston S Churchill, The Second World War: Their Finest Hour, p. 205[/ref]

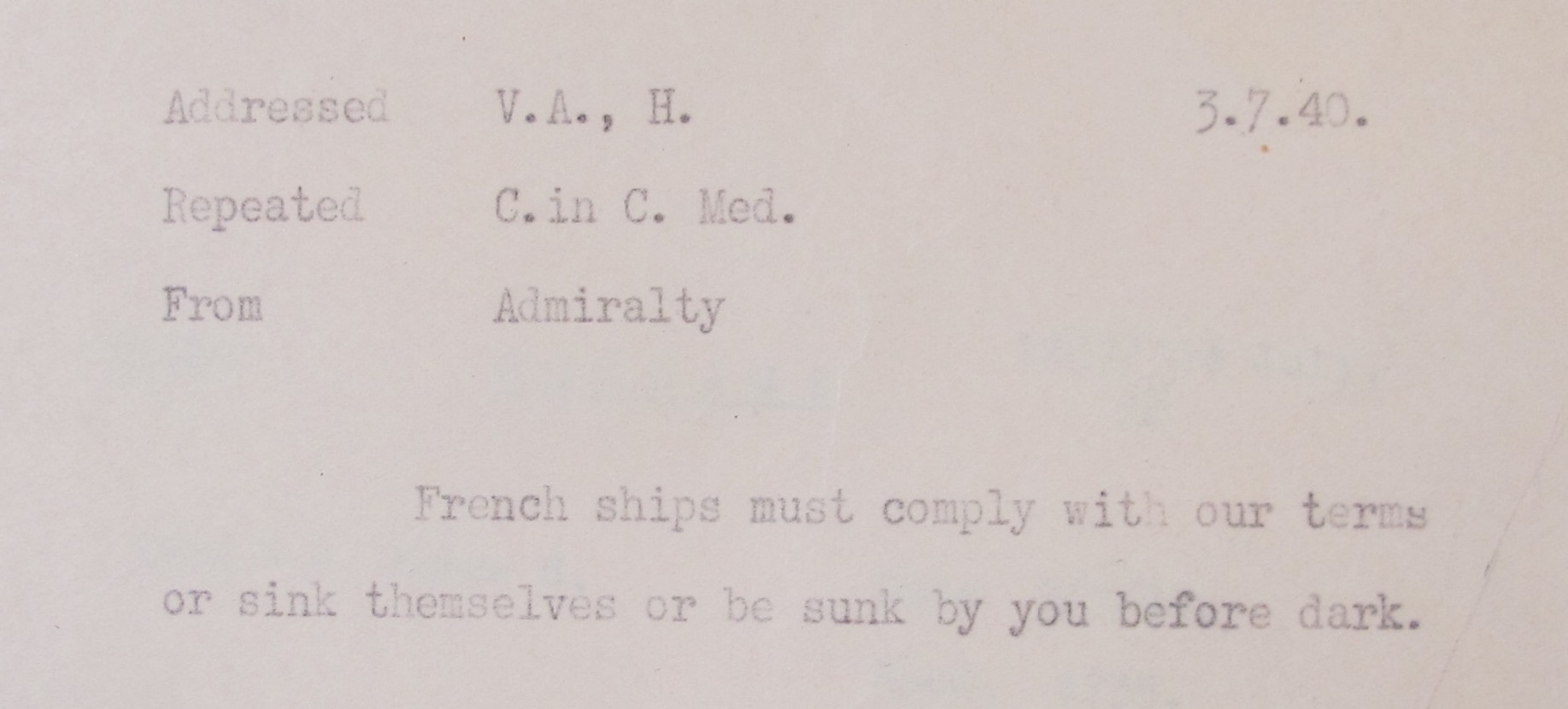

Final instructions to Vice Admiral Somerville (catalogue reference: PREM 3/179/1)

This was not the first time Churchill had been forced to face this extraordinarily difficult problem. In fact, a quarter of a century earlier he had been confronted by exactly the same issue.

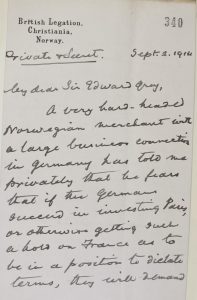

In early September 1914, with the French army being driven back by the Germans, the British government was beginning to face the difficult question of what to do if the French resistance collapsed. A particularly worrying report came from a source in Norway who suggested:

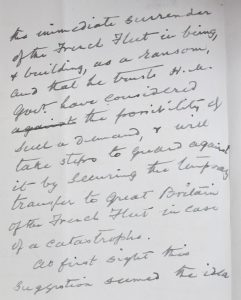

that if the Germans succeed in investing Paris, or otherwise getting such a hold on France as to be in a position to dictate terms, they will demand the immediate surrender of the French Fleet in being and building… he trusts H. M. Govt have considered the possibility of such a demand and will take steps to guard against it by securing the temporary transfer to Great Britain of the French Fleet in case of a catastrophe

- Letter from Findlay reporting rumoured German intentions to seize the French Fleet

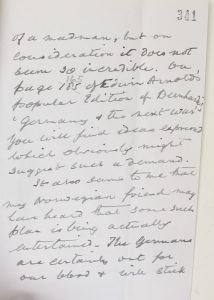

- Letter from Findlay reporting rumoured German intentions to seize the French Fleet, page two

- Letter from Findlay reporting rumoured German intentions to seize the French Fleet, page three

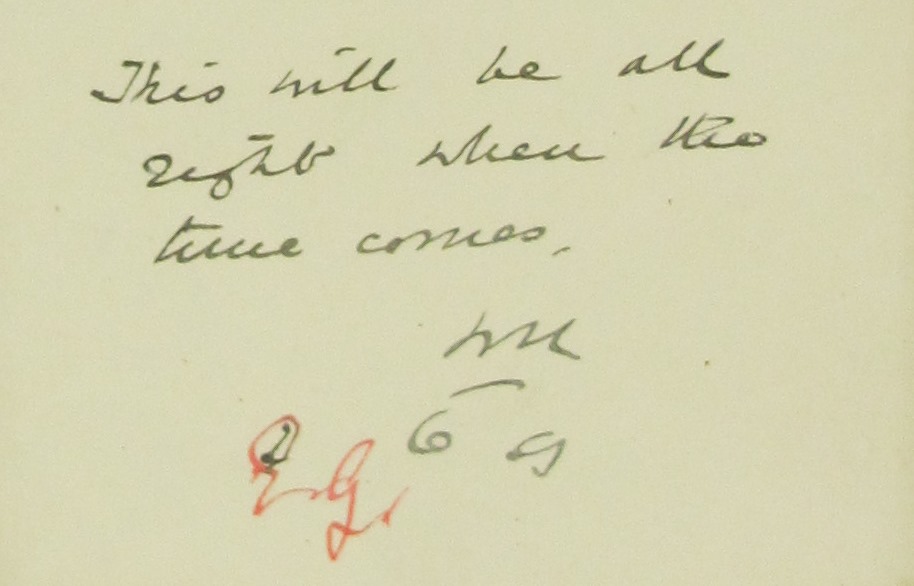

It is evident that the British government had not considered such a possibility. Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, immediately sent the letter to Winston Churchill, who was at the time First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill’s initial response, scrawled on the back of the letter was suitably laconic: ‘This will be all right when the time comes’ (FO 800/69/124).

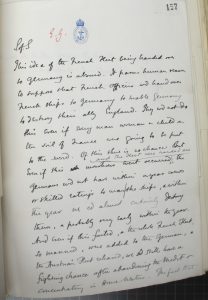

Churchill minute (catalogue reference: FO 800/69/124)

Evidently, overnight Churchill either had a change of mind or was pressed further by his colleagues: the following day he produced a much fuller statement of his views. This document sets out a very different take on events from that which drove Churchill to take the fateful decision 26 years later. He confidently declared that:

This idea of the French Fleet being handed over to Germany is absurd. It passes human reason to suppose that French Officers w[oul]d hand over French ships to Germany to enable Germany to destroy their ally England. They w[oul]d not do this even if every man woman and child on the soil of France were going to be put to the sword. (FO 800/88/52)

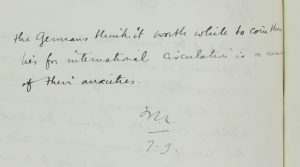

- Note by Churchill written the next day

- Note by Churchill written the next day, page two

Fortunately Churchill’s faith in the French naval officers in 1914 was never tested. It is not clear what drove the shift in Churchill’s position over the course of the intervening years, nor is it possible to assess if he might have changed his mind had the military situation not improved in 1914.

It remains, however, an extraordinary coincidence that twice in Churchill’s career he was forced to consider one of the most unpalatable decisions that any leader can have to take: that of using force against your own allies.

This was not the only such military issue of bombing of Britain’s ‘Allies’ during the Second World War (the attack on the French city of Caen after D-Day and the disasterous bombing of The Hague (to attempt to destroy the V2s and ending up in a large lost of civilian lives and massive damage to people’s houses) both in 1944, although technically The Netherlands was ‘neutral’.

Is it necessary to point out that in one of the photographs that Churchill was wearing a bowler hat and had a gun in his hand, fairly obvious I would have thought.

Hi David,

Yes, it is necessary: we add descriptive text to images so people using screen readers know what the image shows. This description had been put in the wrong place and was showing to everyone; I’ve corrected that.

Best,

Nell