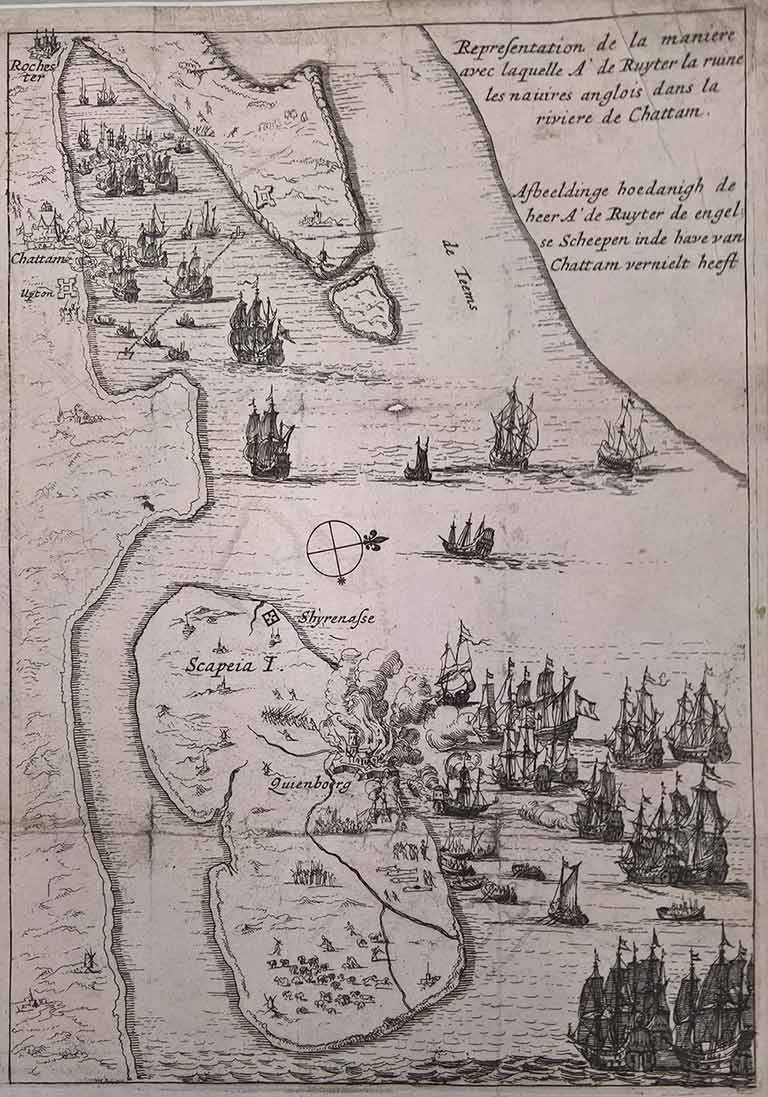

Detail from a Dutch news sheet showing the Dutch attack in the Medway, Amsterdam 1667 (catalogue reference: MPF 1/231; see also Calendar of State Papers, Domestic, 1667, p.177 (CSPD))

In June 1667, the Dutch fleet forced its way up the river Medway to the main naval base at Chatham. There the Dutch destroyed a number of the most powerful and valuable British[ref]1. Between the Regal Union of 1603 and the Parliamentary Union of 1707 it is entirely appropriate when referring to the Royal Navy to use ‘British’ rather than ‘English’. Even though the navy may indeed have been financed entirely from English revenue, from 1603 the Stuart monarchs claimed the title ‘King of Great Britain’. They pursued their British imperial projects using as their tools the diplomatic corps, the army, and the navy – all of which institutions they made ‘British’.[/ref]warships and captured the fleet flagship, Royal Charles, named after the reigning monarch, Charles II. This was a great blow to the king’s image – the largest warships were powerful symbols of national prestige.

The Medway Raid is one of the greatest humiliations in British naval/military history, and as a defeat, is little-remembered today. It is, though, a central episode in the diary of Samuel Pepys and is seen as the last of a ‘triple whammy’ of disasters, following the Great Plague (1665) and the Great Fire of London (1666).

At this time, the Dutch Republic (the United Provinces of the Netherlands) was the leading seaborne trading nation. Intense British-Dutch maritime rivalry led to three wars within less than 25 years (1652-1674). The Medway Raid was the final and decisive major operation of the second of these (1664-1667).

Before the 20th century, economic wars at sea were fought by capturing the enemy’s merchant ships and cargoes. Besides this economic damage to the enemy, selling the captured ships and goods earned revenue for the captor state. But before it could be sold as legal ‘prize’, the nationality of a captured ship had to be determined and proven. This was one of the core functions of the High Court of Admiralty (HCA).

The court records of the HCA – held at The National Archives – provide a unique insight into maritime and global history, and papers from captured ships give underappreciated insight into British naval history. Here, we focus on a critical event in the Anglo-Dutch wars.

The Second Anglo-Dutch War, 1664-1667

During 1664, the war escalated from small-scale colonial strike and counter-strike on the West African coast to full-scale conflict in Europe. That December, off Cadiz, Spain, the British launched a pre-emptive naval attack on a large and rich Dutch merchant convoy returning from the Mediterranean. This act of aggression marks the start of the war proper: the Dutch declared war in January 1665.

The war took place almost entirely at sea, with three titanic naval battles punctuating everyday small actions. These fleet battles were strategically indecisive, but the enormous cost of naval warfare soon identified the stronger of the two adversaries. Britain could not pay for a third consecutive year of full-scale naval deployment and operations.

The greatest savings were found by keeping the largest battleships out of service – the ‘great ships’ of the First and Second Rate. These were held decommissioned in reserve – almost all at Chatham – with removable equipment (such as guns, sails, topmasts, and yards) stored in dockyard facilities ashore, and only a few men aboard for maintenance.

The British downscaled their deployment from a concentrated battle fleet to dispersed squadrons suited to attacking Dutch merchant ships and defending British trade. These squadrons were based at Plymouth, Hull (later in Scotland and Ireland) and Portsmouth – leaving the south-east exposed. The strategic error opened the opportunity for the Dutch plan.

Meanwhile, peace negotiations had already started. The British hoped for a quick end to the war and were complacent about the possibility of a Dutch attack – despite a recent major Dutch raid in the Forth and news of full-scale Dutch naval preparations. The desperate national finances severely impacted on planned improvements to shore defences and on morale: many unpaid sailors and dockworkers were reluctant to risk their lives when the Dutch attacked. Their commanders’ confusion during the attack was also a major factor in the Dutch victory.

The Medway Raid

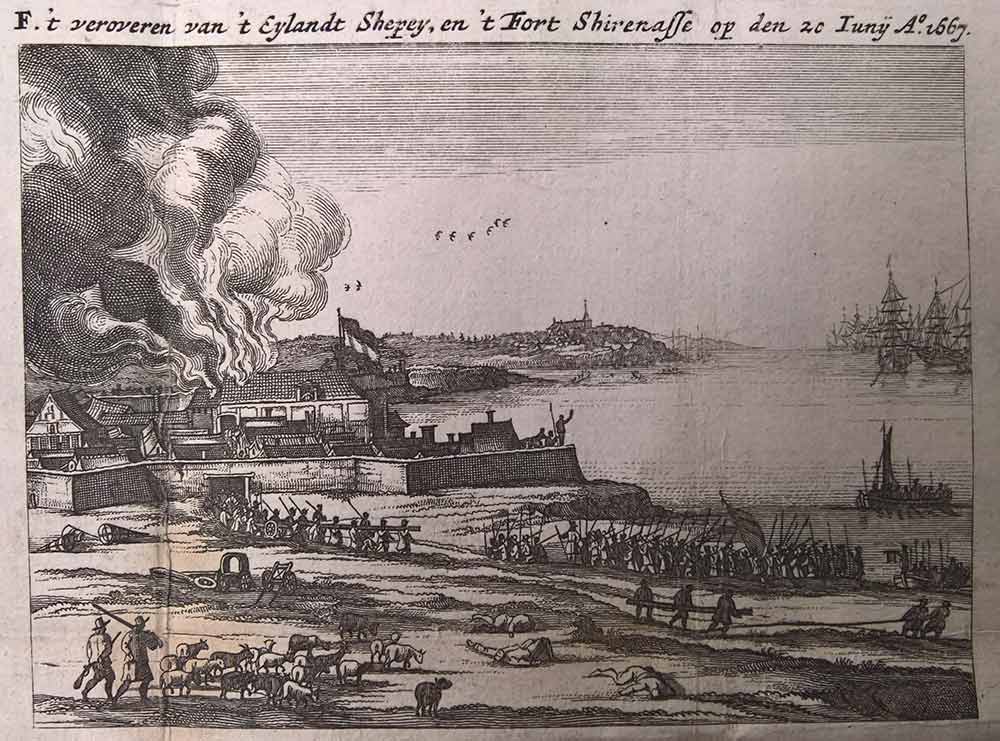

The Dutch quickly captured the fort at Sheerness at the Medway-Thames junction. They then broke through a massive iron chain blocking the Medway down-river of Gillingham. Three warships covering the chain were easily captured or destroyed.

Detail of a Dutch news sheet, showing the capture of the fort at Sheerness (catalogue reference: MPF 1/232; see also CSPD 1667, p.177)

Behind the chain was to be a hastily-improvised barrier of three ‘blockships’ – vessels scuttled (sunk deliberately) to block the river channel. Two were scuttled in the right place but the third ran aground and never reached the correct position, leaving a critical gap.

Through this gap, the Dutch sailed on to reach four of the largest battleships – which the British had neglected to move up-river to more safety. First, they captured the flagship Royal Charles. Further on lay three more, scuttled in the shallow water to prevent their capture. To stop these being salvaged later, the Dutch burnt the substantial parts remaining above-water.

Detail from a Dutch news sheet showing the burning of the ships in the Medway, given as ‘at Rochester’ in the subtitle (catalogue reference: MPF 1/232; see also CSPD 1667, p.177)

The British had now blocked the upper river by scuttling more battleships, and this stretch of river was covered by a strong fort, Upnor Castle. The Dutch, seeing the difficulty of navigating further, decided to withdraw with their two captured prizes.

The impact on Britain’s strength in battleships was appreciable: five First and Second Rates and eight Third and Fourth Rates had been captured, destroyed, or were unsalvagable.[ref]2. Source: Rif Winfield, British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1603-1714: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates (Barnsley, 2009), passim. See also P. G. Rogers, The Dutch in the Medway (London, 1970), especially pp.151-160. A new edition of latter is available (Barnsley, 2017)[/ref] Most of the surviving ‘great ships’ had been scuttled and were in need of salvage.

The Medway Raid soon produced results: the peace negotiations quickly concluded the Treaty of Breda, which conceded more to the Dutch than would have been otherwise.

In the Netherlands, Royal Charles was briefly used as a tourist attraction but was soon broken up for scrap. The stern-piece, however, bearing the Stuart royal arms was preserved and is now exhibited in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

The beginning and end of HMS Sancta Maria

Using the High Court Admiralty (HCA) Prize Papers, held at The National Archives, we can follow the fate of a British warship intimately connected with the opening and final actions of the Second Anglo Dutch War.

HMS Sancta Maria (also known as Maria Sancta) is generally believed to have been a Venetian merchantman. The HCA Prize Papers show instead that the ship was Dutch – Santa Maria van Conceptie (in the original Italianised Dutch, which translates as Santa Maria of Conception) of Amsterdam. The name was easy for Italian merchants to translate as Santa Maria della Concezione in many of the documents.

This large merchant ship had traded since the early 1660s between Amsterdam and Italian ports via Cadiz. It was entirely routine for protestant Dutch owners to ‘catholicise’ their ships with saints’ names in order to ease access to southern European markets. Like other Dutch merchant ships designed for the Mediterranean, Santa Maria was well-armed (26 guns as bought new) for protection against the North African states – the ‘Barbary Corsairs’.[ref]3. HCA 30/1051. Inventory of Santa Maria van Conceptie, August 1660[/ref]

The ship joined the homebound convoy at Malaga in late 1664. Passing westward through the Gibraltar strait the convoy was attacked by a British squadron off Cadiz. Details of the battle are scant. The Prize Papers contain eyewitness testimony that Santa Maria was under Dutch colours and that when attacked by HMS Antelope, only two guns were fired in defence. These were fired by the ship’s master, Lucas Pruijs. His 40-man crew, though, simply refused to fight. When Antelope boarded, Pruijs had no choice but to surrender.[ref]4. HCA 32/2/63. Depositions of Thomas Chandler, Richard Joly, William Bragg, Robert Durant & John Terrick, 25 November 1665[/ref] Commissioned into the British navy, HMS Sancta Maria was given 50 guns and fought in the two great fleet battles of 1666.

At the Medway Raid, it was Sancta Maria that was to be the last blockship sunk behind the chain. The failure to stop the Dutch advance here was a principal cause of the British defeat.

The Dutch gave orders not to burn the grounded ship, but that is precisely what happened. Sancta Maria is often misidentified as HMS Slothany, another Dutch prize (ex-Slot van Honingen) incorporated into the British navy. Dutch naval archives show that Admiral de Ruyter himself got the name wrong, though his subordinate Admiral Jan de Liefde correctly identified the ship as St Maria.[ref]5. Nationaal Archief, The Hague, Admiraliteitscolleges 459. De Ruyter to Rotterdam admiralty, 27 June 1667; ibid. Jan de Liefde to Rotterdam admiralty, 28 June 1667. De Ruyter’s version seems to been accepted. See The National Archives, MPF 1/231 and MPF 1/232[/ref]

Burning of the English Fleet near Chatham (Schellinks painted another version, the museum description of which gives the grounded vessel on the left of sunken ships as Santa Maria), Schellinks, 1667 (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, SK-A-1393)

The Prize Papers

While it focuses on foreign ships HCA is a strong source for British maritime history – the British navy absorbed a particularly large number of former prizes in the third quarter of the 17th century. British merchant shipping also benefitted in a similar way.

During the course of its history, Britain captured thousands of ships. Records of many of these cases are preserved in the enormous HCA archive. The survival of maritime court records and papers on this scale is unique. The Prize Papers in HCA 30 and HCA 32 contain papers found on the captured ships. Some were papers belonging to the master and relating to the ship and cargo.

The real highlights, though, of the Santa Maria of Conception collection are not the documents already mentioned. The ship’s master, Pruijs, kept a magnificent business archive of over 140 letters, as well as another of personal letters from his wife.[ref] 6. For more on the business archive of Lucas Pruijs and the pre-war trade of Santa Maria van Conceptie, see Marie-Christine Engels, ‘“De Turcken behoeft niet te vresen”. Impressies uit het ‘scheepsarchief’ van Lucas Pruijs in de jaren vóór de Tweede Engelse Oorlog, 1661-1664,’ in Erik van der Doe, Perry Moree & Dirck J. Tang (eds.), De gekaapte kaper. Brieven en scheepspapieren uit de Europese handelsvaart, Sailing Letters Journaal IV (Walburg, Zutphen, 2011), pp. 27-36.[/ref] As ships were vital for sending post, the Prize Papers also contain letters as mail put aboard for delivery.

Perhaps the brightest jewels in the HCA Prize Papers are the private letters written between ordinary people. The lower social classes – the bulk of humanity – are almost completely anonymous in history. Where they did write letters to each other these have only very rarely survived – paper was then expensive (valuable) and is a fragile and recyclable commodity. Here, their voices can be heard again.

You mention the ‘British’ and ‘Britain’ when of course it was England and Scotland would not have been involved.

Hi David,

The first footnote explains the author’s use of British – hope that helps.

Best,

Nell

This is an interesting article, but I’m surprised Upnor Castle doesn’t get a mention. It was meant to protect the warships moored at Chatham Dockyard but, despite a valiant attempt, was unsuccessful in repelling the Dutch fleet. The castle is well worth a visit and affords excellent views of the route the Dutch fleet would have taken up the Medway.

Please can you give any more information about new discoveries in HCA, particularly those relating to the English / British ships, if any have come to light.

[…] The Medway Raid and 17th century maritime warfare […]

On 8th June 2017 a fleet of some 35 yachts sailed up the Medway, lead by the Dutch Navy training ship URANIA and on Upnor Castle the Dutch Prince Maurits took the salute.

350 years after our successful raid!!

If you want photos I can send you some.

Kind regards,

Theodor Strauss

Surely the letters will rank with Pepys diaries of the period. I hope they will be published.