This blog is published as part of Disability History Month (22 November to 22 December 2019).

What happened in the medieval period when people became mentally ill? Modern advances in diagnosis and treatment, and a monolithic view of pre-modern culture, might entrench opinions that former attitudes to people undergoing the confusion and uncertainty of changing mental health were uniformly brutal and uncaring. As with many aspects of medieval or early modern life, however, surviving historical records unveil a more complex picture of assessment, treatment and provision. A good range of evidence comes from specialist or communal inquests into the mental state of people with property who became ill during their lives. The 1383 case of Emma de Beston, a widow from King’s Lynn in Norfolk, gives us a glimpse of a diverse range of attitudes and approaches to this subject.

Several cases regarding people classified (in contemporary language) as idiots also reveal medieval attitudes to mental illness, disability and incapacity at a communal level. Some of these inquests appear in the inquisitions post mortem at The National Archives, others escaped the great Victorian enterprise of document sorting and classification, or were identified much later, and are now in a collection of miscellaneous inquests in record series C 145. Emma’s case is found in the file at reference C 145/228/10.

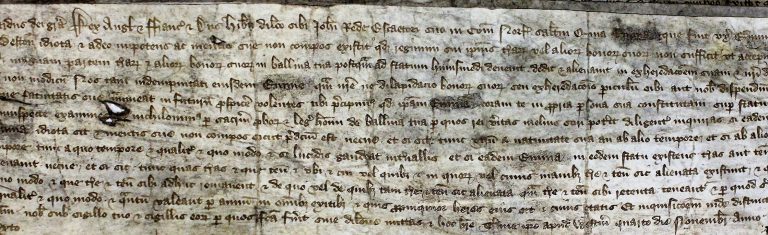

The order for the escheator of Norfolk to begin the process of assessing Emma de Beston’s mental capacity. Catalogue ref: C 145/228/10, no. 5

Mental illness, land and the law

People born with severe mental incapacity, but who were nevertheless heirs or heiresses to real or personal estate, were protected by law as part of the prerogativa regis (or royal prerogative). They had the status of wards of the Crown and their property would be managed on their behalf until they recovered. In most of those cases it was assumed that recovery would never occur. Provision should have been made for their welfare from the profits of the lands. Ensuring that those estates kept their value benefited the king too; not least because, once in Crown hands, possessions became parcel of the monarch’s resources available as royal patronage: the more productive and valuable the property, the higher the fee and annual rent that could be charged. The case of individuals in such a state of permanent mental incapacity is harder to judge because the evidence of their illness soon dries up as the government’s records focus on the land and not the person.

Those who became insane during their lives were to be provided for by the king without losing rights to their estates. This situation seemed to have evolved through custom and practice, rather than statute. There was also scope for regional and communal differences in how care was provided. Most often, those people who developed symptoms were left in the protection of their families and communities. Where the right level of care was not possible, some form of diagnosis was derived from interviews with the person’s kin and a process of inquest through a jury. It often involved examination of the ill person themselves. A major concern was to establish if lucid intervals occurred when estates could be managed in person. The solution was backed by force of the law[ref]For more detail on the legal status of those with mental incapacity see E Buhrer, ‘Law and Mental Capacity in Late Medieval England’, Reading Medieval Studies, XL (2014), pp. 82-100.[/ref].

Emma’s story

Emma de Beston’s case arose when her state of mind began to raise concerns within her family. Once her behaviour became unusual and Emma began to transfer parts of her estate erratically, her family acted quickly to preserve her lands so they could be passed intact to her heirs. The Norfolk escheator – the official who looked after the Crown’s inherent rights at a local level – examined Emma in person and concluded that she had been driven insane by the ‘snares of evil spirits’. Her lands and goods were put into the care of a kinsman who had no hereditary right to ownership but who was assigned by the Crown’s officers to look after her interests.

Since Emma did own valuable property, it was not long before several other people, including the mayor of King’s Lynn, colluded to try to get their hands on it. She did not contest her incapacity, but petitioned that this arrangement for transfer of her estate was a process that suborned the law and denied her interests. This suggests that she enjoyed periods of lucidity against an overall pattern of decline in her mental state. During those bouts of clarity, her concerns for the future allowed Emma to use her status as a landowner to take some legal and administrative steps to protect her lands from predators. As a result, Emma asked for a group of officials who were unconnected to her or her community take possession of her lands. In July 1383, she was summoned before royal commissioners at Lincoln for an assessment of her mental capacity.

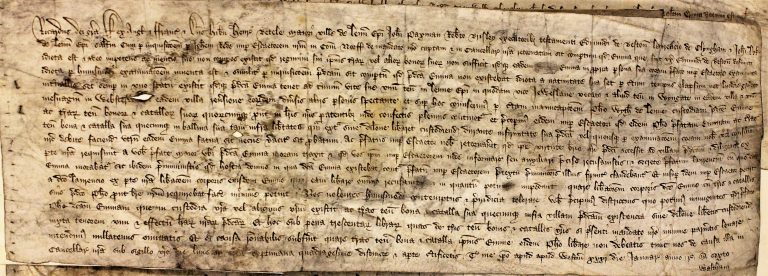

A letter of 31 January 1383 from Richard II to the authorities in King’s Lynn setting out the steps to be taken to safeguard Emma de Beston’s lands. Catalogue ref: C 145/228/10, no. 1

Assessing Emma’s state of mind

The Lincoln officials were tasked to decide on Emma’s state of mind. Although they had little knowledge of Emma’s life in Norfolk, it seems likely that they were chosen for their expertise in deciding matters of mental illness. She was asked a series of questions – what town was she in; what day of the week was it; what are the days of the week; could she name the three husbands she had had; had she any children and did she know their names; how many shillings in forty pence; would she rather have twenty groats or forty pence? This mixture of tests of general knowledge and memory and, in other cases, skills, was a simple but effective way of judging someone’s mental state; some of which remains part of modern assessment and diagnosis techniques.

Other approaches were tried before the examiners concluded that Emma was of unsound mind – in contemporary language, ‘having neither sense or memory nor intelligence to manage herself or her goods, with the face and countenance of an idiot’. As a result, her personal custody was confirmed with her then guardian, but her lands were assigned to four burgesses from King’s Lynn. The profits of her estates paid for her care, clothes and maintenance. Emma died in that state on 30 December 1386 and left her estate to her niece, Isabel.

Where possible, it was crucial that the ill person testified and had some agency in the process that would decide how their interests were safeguarded. While much of this methodology looked to secure the rights to lands and goods, it also provided for the individual at the centre of the process. Emma’s story shows that medieval institutions, the law, and communities were neither barbarous nor monolithic in their approach to those who could not care for themselves.