In the high summer of 1318, a nun of the priory of St Clement near York – Joan of Leeds – staged a daring escape from her convent. She left behind a life of poverty, self-denial, chastity and obedience to the Rule of St Benedict, to which she had apparently struggled to conform. Joan feigned a serious illness and then faked her own death.

In the high summer of 1318, a nun of the priory of St Clement near York – Joan of Leeds – staged a daring escape from her convent. She left behind a life of poverty, self-denial, chastity and obedience to the Rule of St Benedict, to which she had apparently struggled to conform. Joan feigned a serious illness and then faked her own death.

With the help of a group of friends (possibly even some fellow nuns), she fashioned a dummy in her own image and procured its burial – probably within the cemetery of the convent – while she fled to Beverley, some 30 or so miles to the east. There, she discarded her religious habit. Worse still, she ‘involved herself irreverently and perverted her path of life arrogantly to the way of carnal lust and away from poverty and obedience’. The inference is that she was in a relationship with a man.

AN 14/114 British Railways Beverley Minster poster, artist Kenneth Steel

It was certainly not uncommon for members of monastic communities, men and women, to struggle to come to terms with their spiritual vocation, and ultimately abandon it. It was also not uncommon for sexual misconduct to be ‘exposed’ during monastic visitations: periodic inspections of the behaviour of monks and nuns by archbishops, bishops and their officials. However, Joan’s story is unusual, even by the standards of the time.

It is recorded in a command from William Melton, Archbishop of York, to the Dean of Beverley Minster. He was commanded to summon Joan to return to her house for the safety of her soul. It is not entirely clear how the archbishop came to hear of the ‘scandalous rumour’ concerning Joan’s fate. Perhaps she had confessed; perhaps someone recognised her. Sadly, what came of his command is not known, and Joan’s apostasy – her runaway status – fades into obscurity.

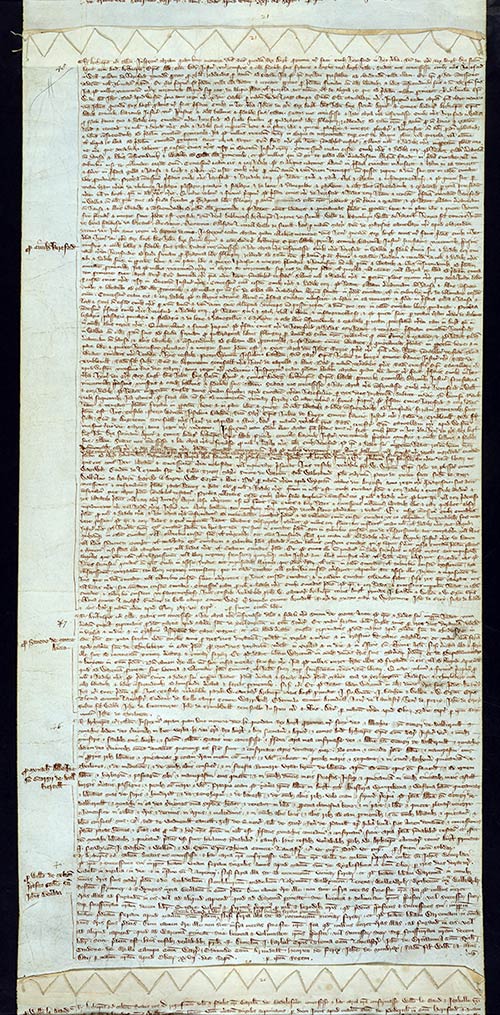

The story is recorded in William Melton’s archiepiscopal register. It is a tightly-bound volume of correspondence and church business, copied onto parchment (animal skin) in heavily-abbreviated ecclesiastical Latin for the years 1317 to 1340, and is held at the Borthwick Institute for Archives at the University of York.[ref]York, Borthwick Institute for Archives, YDA ABP REG 9A, f. 326v (11 August 1318). Click here for a digital image of this folio.[/ref] It has been known in academic circles for several decades and a Latin transcript of the entry was recently published.[ref]The Register of William Melton, Archbishop of York 1317-1340. Volume VI, ed. David Robinson (York: Canterbury & York Society 101, 2011), no. 74, pp. 17-18. For an overview of monastic life see Eileen Power, Medieval English Nunneries c. 1275 to 1535 (Cambridge, 1922).[/ref] However, it has been brought to much greater public attention since the commencement on 1 February this year of a new academic research project and its translation into modern English. There is also the possibility of a range of new discoveries relating to spiritual, social and political life in the medieval North.

Generously funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (ref. AH/S001565/1), ‘The Northern Way: Archbishops of York and Northern Identity, 1304-1405’ is a collaboration between medievalists and archivists at the University of York and The National Archives, with the support of the Chapter of York Minster. I am the co-investigator on the project; for the next 33 months, The National Archives will be working closely with Professor Sarah Rees Jones and our research team, split between the two organisations.

AN 14/210 British Railways York poster (showing York Minster), artist Kenneth Steel

The project essentially aims to investigate the relationship between Church and State, centre and periphery, in the 14th century. It also aims to explore the spiritual and social lives of people across the North. This was a century scarred by death, disease and warfare. Joan of Leeds’ escape coincided with the end of a severe famine that had gripped Europe for three years, and the Black Death of 1348 to 1349 decimated the population. English armies ravaged northern France, and Scottish armies frequently harried northern England. However, the century also witnessed an artistic and literary flowering, most evident in the enlargement and glazing of York Minster.

It was also a period during which successive archbishops of York – from William Greenfield to Richard Scrope – occupied senior positions in royal government and as intimates and confidantes of kings, although Scrope was driven to lead a northern rebellion against Henry IV in 1405.[ref]P.J.P. Goldberg (ed.), Richard Scrope: Archbishop, Rebel, Martyr (Donington, 2007).[/ref] The project aims to digitally index the surviving registers for the eight archbishops who reigned during the century, and to make their content accessible to a wider audience. It will also survey, and make cross-searchable, selected documents from the vast archive of medieval royal government held here at The National Archives, as our collections relating to religious history are not that well known.

For example, we hold thousands of petitions to the Crown in our series SC 8 and C 84. These document complaints about matters as varied as the repopulation of the Church after the Black Death, disputed elections to religious office, clerical taxation (and requests for exemption from tax due to warfare or famine), and appeals to the secular for assistance in restraining those contravening ecclesiastical law. These link to numerous other series: notably the Chancery rolls, upon which the Crown recorded its outgoing correspondence, and the warrants documenting on whose authority such letters and grants were made. They also feed into what are known as Significations of Excommunication (series C 85).

C 53/101 m21 Charter Rolls, July 1314-

These record instances where the Church asks the Crown for assistance in bringing to heel those who had been excommunicated in such matters as non-payment of tithes, assault on the clergy, necromancy, heresy and defamation. They are the kind of letters that might have been issued in the case of Joan of Leeds, if she had remained at large and ‘contumacious’ following her flight in 1318 – although no trace has yet been found. We hope that the project can track documentary trails through the archbishops’ registers and government archives.

Another key element of the project is to explore the multiple roles of archbishops at the centre: their relationship with kings and other officers of state; their role as creditors; their patronage of clerks; and the creation of personal networks at the heart of government. By examining some of the main administrative records of Chancery and Exchequer, we aim to find out the extent to which royal government was imprinted with a northernness during the 14th century. Did northern archbishops struggle to maintain a northern identity in political as well as spiritual matters? They were often distant from the heart of their main sphere of influence, the northern province (not only the diocese of York but also of Carlisle and Durham, where the archbishops acted as metropolitans).

Ultimately, over the next three years, The Northern Way hopes to bring fresh insights into the religious, social and political history of the British Isles during one of its most turbulent centuries. We also hope to make some of the most important records – which are notoriously difficult to access – more readily available to researchers of all interests and at all stages of research.

You can follow the project on Twitter (@tnorthernway) and on the project website.

to what extent are you considering developments in Ireland, Wales and Scotland in your investigartions into the religious, social and political history of the British Isles?

Hi Sylvia. Thanks for your question. In principle, the project is focussed on examining the dual role of the archbishops of York in the spiritual and political life of the north of England and at the heart of English government as advisors to successive kings. However, there will naturally be occasions where relations with Scotland in particular will loom large during periods of military conflict and/or diplomatic negotiations. Similarly, as we examine the personnel of the northern diocese and their networks, I would expect, for example, to find evidence or recruitment and/or transfer of men from other dioceses and involvement in the business of the Scottish and Irish church. You cannot take the history of medieval England out of its British Isles and European context. So while the primary focus of the project is northern England, we hope to find much that will interest historians of the British Isles as a whole. Paul.