The following is an account of my placement at The National Archives, for which I have to thank the Midlands4Cities Doctoral Training Partnership funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

I applied for a placement at The National Archives to learn how to find and approach documents for my PhD thesis on English people learning the Italian language during the Tudor period. I was keen also to look at different ways of employing research skills outside academia, and explore how history could be promoted through public engagement.

This blog will present what I have learned at The National Archives through the prism of my interactions with the documents known as SP 46/92 and SP 46/93.

Chaos and order

These quite intimidating alphanumerical sets became less esoteric and abstract thanks to the explanations of Ruth (my supervisor at The National Archives), Ada (from the Catalogue and Taxonomy team), and Euan and his colleagues behind the Postgraduate Academic Skills Training (PAST) programme. Speaking of PAST, I highly recommend to anyone starting a research project that would benefit from archive documents to book a place for this open workshop (now in online format).

Coming back to the subject of alphanumerical sets, I found out that, besides being key jargon during team meetings, they are also useful references for anyone to help navigate Discovery (the ‘Google’ of The National Archives’ website) with precision.

As my placement was taking place online, I was deprived of physical points of reference, which created initial confusion in my understanding of the structure of the archive – I felt as if I were faced with a scattered collection of Russian dolls. However, after some practice with Discovery, the pieces started to fit into place, literally.

SP 46 is a series called ‘State Papers Domestic: Supplementary’ (covering the period 1231-1829) within records of the State Paper Office (covering the period 1231-c.1888) and the number after the slash (/) represents the piece (e.g. volume, folder, box, file etc). Browsing down the hierarchical tree, SP 46/92 and SP 46/93 are two volumes that, together with SP 46/90 and SP46/91, form a sub-series called the ‘De Renzi Papers’ because they hold documents regarding a settler in Ireland (from 1604 to 1642) called Matthew De Renzi (1577-1634).

The ditch

My assignment was to read these documents folio by folio, providing an item-level description of the two volumes SP 46/92 and SP 46/93. Fortunately, somebody had already completed the same work for the previous volumes (SP 46/90 and SP 46/91), giving me a model for cataloguing and more context on De Renzi himself (also known in the records as Matheo de Renti, Matteo Derinzy, Matthewo De Rensy, De Reyns, etc)[ref]More information on Matthew De Renzi can also be found in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and articles by Brian Mac Cuarta.[/ref].

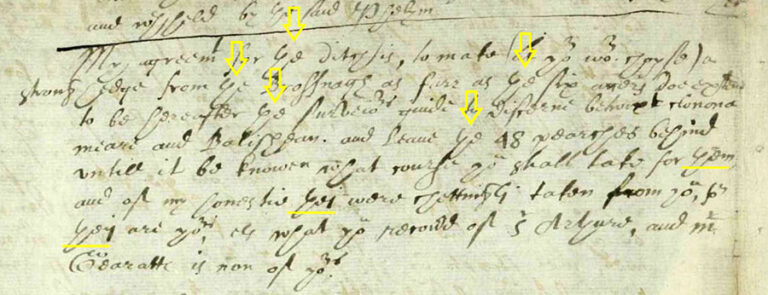

Initially, I had difficulty understanding the 17th-century handwriting in the documents, but Ruth patiently helped me to develop my palaeographic skills. Essential elements for learning are the 3 Ps: practice, patience and patterns.

For example, in the first extended document that I tried to crack (SP 46/92, ff 6-7), I noticed a repetitive ‘sign’ before names. This was the article ‘the’, so I could identify also the common combination of the letter ‘th’ in other words such as ‘them’ and ‘they’.

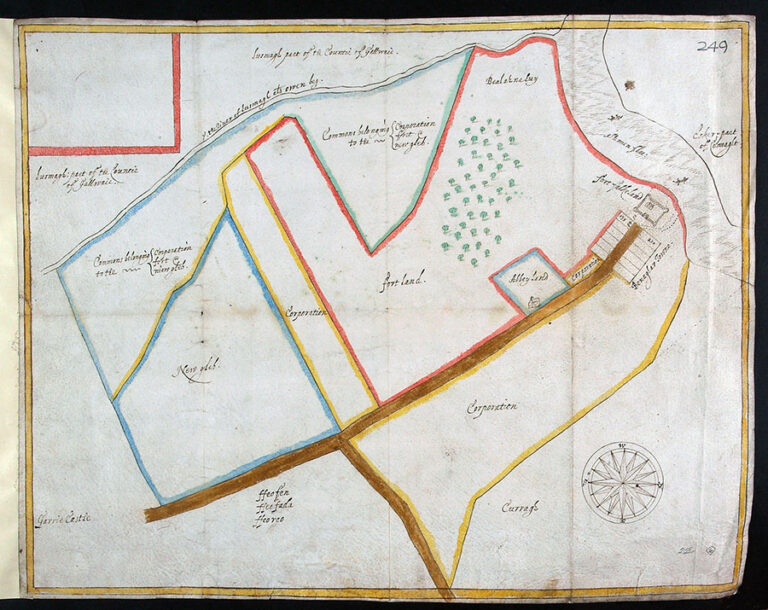

To my initial disappointment, after my wobbly attempt at transcription, and Ruth’s corrections, the document turned out to be an agreement for digging a ditch with a bog, three ‘meres’ (that I know now are small bodies of water), and an oak tree as protagonists. To be honest, I was expecting something more exciting as a reward for my palaeographic efforts. However, analysing the document with more rationality, I can say that it is a small, but significant, piece of the puzzle of De Renzi’s life.

In fact, in the Gaelic midlands, in the townland of Clanona, digging a ditch was a declaration – and instrument – of his administrative authority. He was a merchant perhaps of Italian background, born in Cologne (Germany), who as a consequence of a trial for bankruptcy in London fled to Ireland, to a remote outpost of the growing English empire, to redeem himself and build a new life as a middle-ranking administrator, planter and businessman[ref]In a letter in Italian to Robert Cecil (1563-1612), Secretary of State of England and Lord High Treasurer, De Renzi asked forgiveness and the opportunity to reside in Ireland to repay his creditors. Cecil Papers, Vol. 118, (Oct 15, 1606).[/ref]. De Renzi was an outsider among the new English settlers in a wild land where both nature and locals, that he described as ‘barbarous’, tended to be hostile.

Once settled in this land of bogs and trees next to the River Shannon, De Renzi needed to protect his legal rights on several parcels of land, and his life, especially against the powerful and aggressive local family of Sir John Mac Coghlans[ref]Clanona was in the barony of Garrycastle (also lordship of Delvin Mac Coghlan).[/ref].

![Ink drawing of a map of the border between Sir Arthur Blundel’s and Mr. Derensy’s [Matthew De Renzi] land in the townland of Clanona. The pricked lines are ditches and the River Shannon is on the right-hand margin.](https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/30155159/michele_1-768x626.jpg)

So the ditch eventually concealed more than I had imagined, because a document always tells a story if placed in the right context and interrogated with the right questions – as some seven-year-old children reminded me during a workshop on the Great Fire of London at The National Archives. On this occasion, the Education team presented some original documents to a Year 2 class, in such a way that they could work out for themselves where the Great Fire originated and how the political reaction affected daily life. This was a great model for the development of analytical, critical and creative skills that demonstrates, once again, the value of studying history for our society.

On the other hand, De Renzi’s story provides an example of how historical information can be used dangerously, promoting the superiority of one culture on to another. Being aware of the power of language and history, De Renzi studied colloquial and classic Irish language and history, gaining the respect of several Gaelic learned families[ref]e.g. SP 46/92, folio 188 is a eulogistic biography and poem to De Renzi composed by the Mac Bruaideadha, a family of historians from Thomod, that praise his linguistic skills and literary achievement as the writer of a Gaelic grammar, dictionary, and chronicle, now lost.[/ref]. However, on several occasions he proposed to the English administrators of Ireland that they repress Gaelic language and culture in order to break the resistance to the colonisation of the island.

Epilogue

I have not finished cataloguing SP 46/92 and SP 46/93 (yet), so I feel that there is much more to learn about De Renzi[ref]I am also cataloguing a piece from PRO 31/9 ‘Roman Transcripts’, but that is another story to tell.[/ref]. Moreover, documents regarding him are also in another series, called WALE 31. To my amazement, some of them are kept 150 metres below the ground in a former salt mine in Cheshire.

Also, some documents regarding De Renzi were probably in the Public Record Office of Ireland and destroyed in 1922 during the Civil War. The National Archives is involved in an international project, called Beyond 2022, that will rebuild a virtual version, open to everyone, of the destroyed archive.

Other futuristic projects are Deep Discoveries, which will use artificial intelligence to search and match images across digitised national collections, and ARCHANGEL, that aims to guarantee access and integrity of the data thanks to distributed ledger technology.

It was exciting and encouraging to meet so many people at The National Archives who are so passionate about preserving, cataloguing, researching and making available our past to a wide range of audiences, without forgetting to look to the future. Thank you.

Michele Piscitelli is a student at the University of Birmingham.

Michele

the awful De Renzi handwriting has caused much cursing from previous archivists and researchers – congratulations on your success and on this very perceptive and interesting blog. Don’t forget to come to Kew once we reopen!