Our early modern volunteering team have been busy cataloguing a series of documents, SP 8, known as ‘King William’s Chest’. It is a collection of State Papers personally curated by William himself for his own reference. Among the official papers in it relating to governance and the wider European War, we were delighted to find expressions of the most tender personal sentiments.

In this blog, Richard Knight, one of our long-standing volunteers, highlights some of this most affectionate correspondence.

Ralph Thompson M.A., Volunteer Supervisor, The National Archives

The reign of Britain’s only joint monarchs – King William III and Queen Mary II (1689–1694) – was marked outwardly by religious controversy, war and disputed succession. But the personal life they shared in those troubled times was loving and deeply romantic.

‘I love you more than my life, and desire only to please you’, Mary wrote to William in July 1690, shortly after he’d left London for Ireland.[ref]SP 8/7/73, f.150, 3 July 1690[/ref] He’d gone there to wage war against Mary’s father, the deposed King James II.

James had been forced from the throne 18 months earlier by a Dutch-led invasion of England. William was at its head. After that, with William’s troops patrolling the streets of London, parliament offered him the crown jointly with Princess Mary. It was a sequence of events commonly known as ‘the Glorious Revolution’.

Mary and William’s marriage

In 1677, when Mary’s father told her she was to marry her cousin William of Orange, the Dutch Stadtholder, she’d ‘wept all that afternoon and all the following night’.[ref]Bowen, Marjorie The third Mary Stuart: Mary of York, Orange & England, being a character study with memoirs and letters of Queen Mary II of England, 1662-1694 (John Lane, 1929). Transcriptions of most of the letters in this blog appear in this work. p42. [/ref] Lady Mary Stuart was only fifteen. William was eleven years older and four inches shorter. She was beautiful, romantic, cultured and passionate. He was unfashionable, abrupt, pock-marked and taciturn.

And yet, surprisingly perhaps, their marriage was a personal success as well as a political one. Mary adapted well to life in Holland and, for 11 years, she was very happy there.

Mezzotint, 1677

NPG D9227

© National Portrait Gallery, London

As William took leave of her, on his perilous invasion of England in the autumn of 1688, he bade the governing body of the Dutch Republic, the States-General, to ‘take care of my adored wife who has always loved this country as if it were her own.’ [ref]Bowen, Marjorie The third Mary Stuart: Mary of York, Orange & England, being a character study with memoirs and letters of Queen Mary II of England, 1662-1694 (John Lane, 1929). Transcriptions of most of the letters in this blog appear in this work. p42. [/ref]

Mary felt loved in Holland and lamented the different attitude to her which she felt while in England.

Separated by war

It often fell to Mary to watch her husband go off to war. In the summer of 1690, the theatre was Ireland – a conflict from which cultural, political and religious symbols remain reference points to the present day, although the Jacobite war in Ireland was essentially more about land ownership than purely matters of faith.

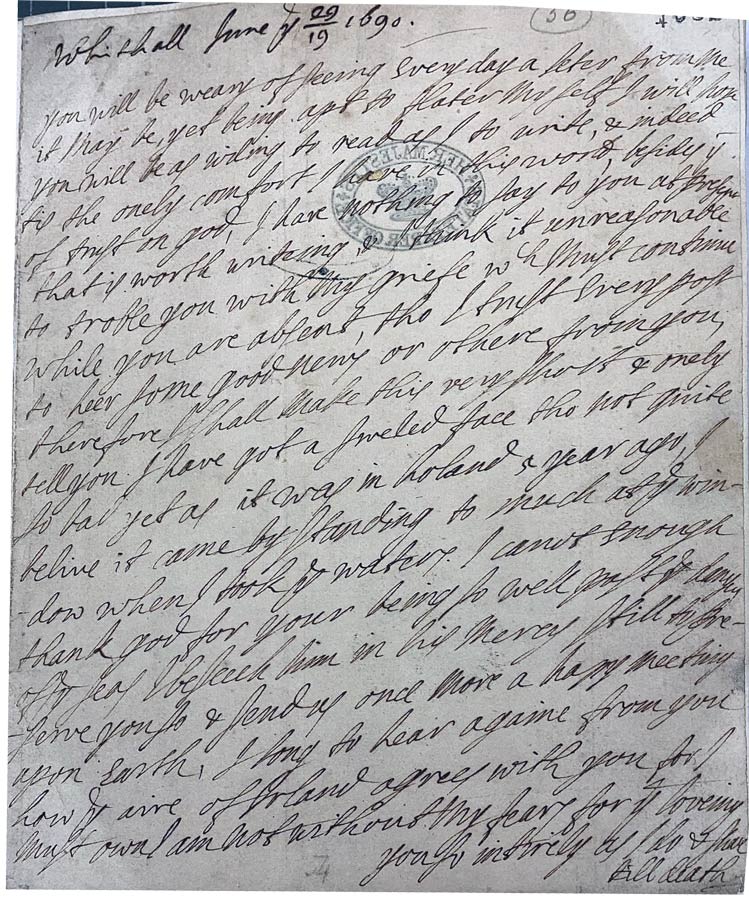

While he was away, Mary wrote to her husband from Whitehall Palace at every available post, sometimes daily. Her thirty-five surviving letters in William’s Chest all speak of Mary’s concern for his welfare.

In the first of them, despatched three days after her asthmatic husband landed at Carrickfergus, she wrote:

‘I long to hear again from you how the air of Ireland agrees with you, for I must own I am not without my fears, for the loving you so entirely as I do, and shall till death’.

SP 8/7/56, f.108b

Mary’s anxiety for William would be unimaginable ‘to any who loves lesse than myself’, she told her husband, but her public duties forced her to put a brave face on everything.

‘I must grin when my heart was ready to break and must talk when my heart is so oppressed I can scarce breath’, she wrote, although conceding, ‘I dissemble very ill to those who know me’. Her friends did not necessarily include those of her sister Anne. Sarah Churchill, Countess of Marlborough was definitely not one. Even so, she pitied Sarah on account of ‘great compassion for wives when their husbands go to fight’.[ref]SP 8/7/164, ff.338-41: 26 Aug 1690[/ref] The Earl was then heading to join William in Ireland.

Ruling in William’s absence

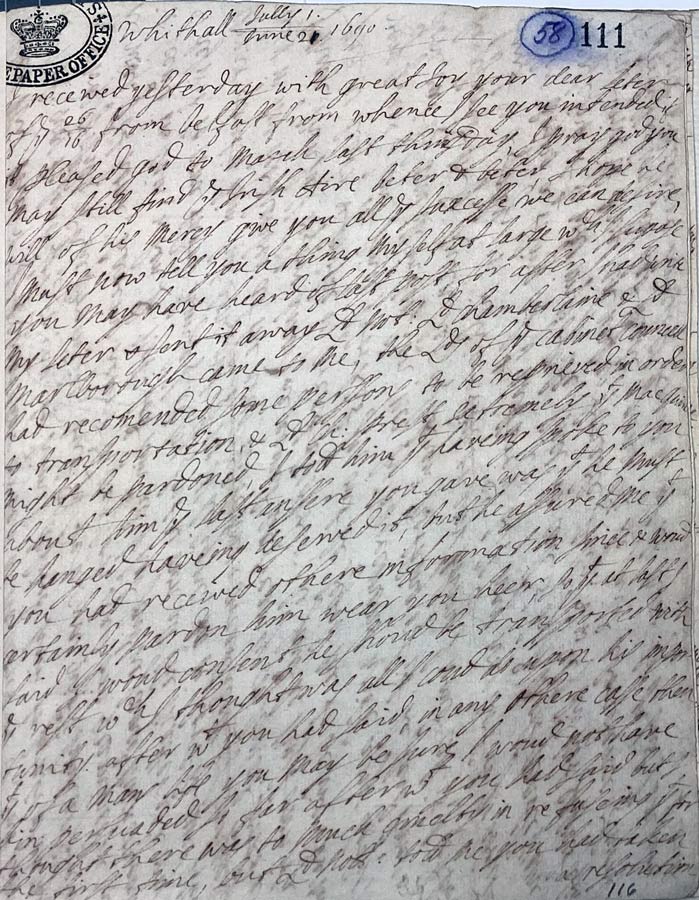

When not on campaign, William took sole control of administration. As Queen-regnant, in his absence, Mary was left in formal charge of government, heading a nine-man ‘cabinet council’. She had overall constitutional responsibility but lacked effective authority, and Mary found her duties irksome. ‘Do but continue to love me’[ref]SP 8/7/58, f.111[/ref] she wrote to her husband ‘and I can bear all things else with ease’. She had lots to bear.

A defeat at sea by the French, off Beachy Head during the Nine Year’s War, left the Royal Navy in disarray. Sensitive decisions had to be taken about appointing admirals, and placing the admiralty in commission. The cabinet council itself was factious and suspicious of French and Jacobite influence, and it was sometimes in ‘great heat’.[ref]SP 8/7/103, f.210: 18 July 1690[/ref] Some members believed that ‘what’s decided in council is next day reported to France’.[ref]SP 8/7/85, ff.172-5: 7 July 1690[/ref]

Mary’s letters

All this the Queen meticulously passed on to the King, her letters a curious blend of the official report and the love letter. They were very often written last thing after a busy day. ‘I am now in my bed having bathed and am so sleepy I can say no more but that I am ever and entirely yours’.[ref]SP 8/7/92a, f.190: 12 July 1690[/ref]

William’s letters also sometimes reached her after retiring to bed and were received with great relief. But when delays stopped the post, anxiety mounted. ‘You cannot imagine the miserable condition I was in last night’, she wrote to William. ‘I think had not your letter come as it did I should have taken sick with fear for your dear person’.[ref]SP 8/7/137, f.281: 12 Aug 1690[/ref]

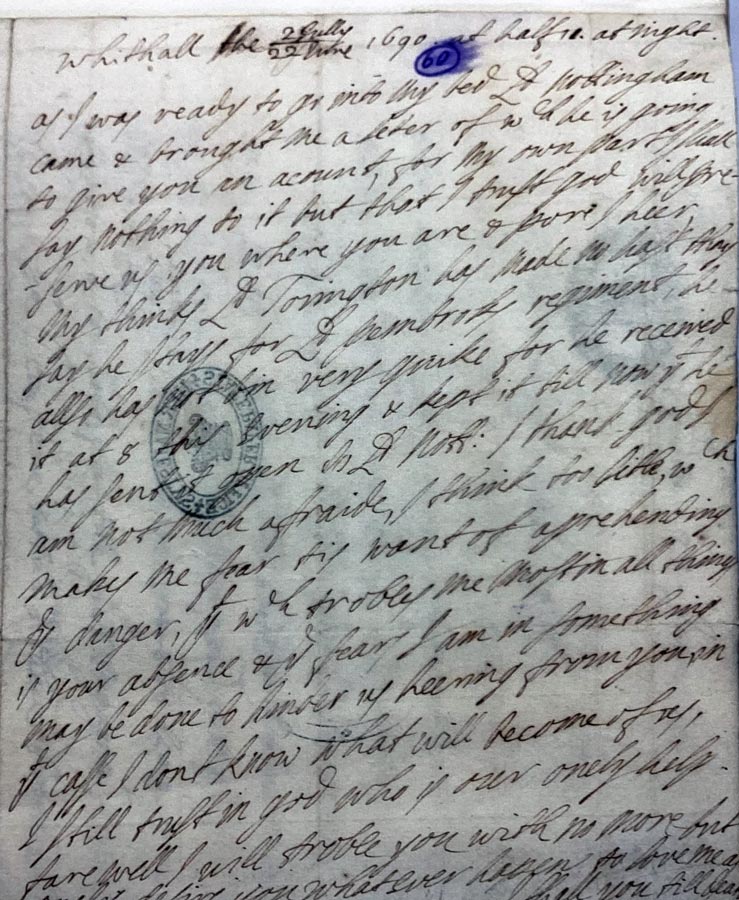

Her own letters always ended with endearments. ‘My heart is more yours than my own’.[ref]SP 8/7/94, f.194: 13 July 1690 & SP 8/7/103, f.210: 18 July 1690[/ref] Or ‘Farewell. I will tro[u]ble you with no more, but onely desire you, whatever happen[s], to love me, as I shall you, till death’, she wrote.[ref]SP 8/7/60, f.117[/ref]

Waiting for William’s return

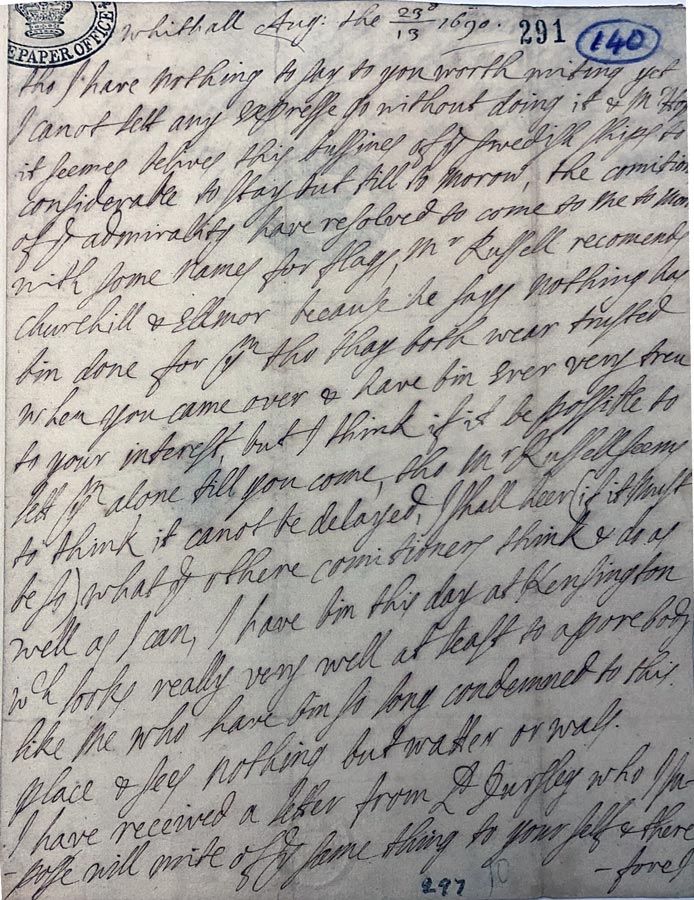

William’s return from Ireland was continually delayed. ‘[T]is impossible to believe how impatient I am for that, nor how much I love you which will not end but with my life’.[ref]SP 8/7/140, f.291[/ref]

Kensington Palace was prepared for his homecoming. Their apartments were aired and ready, she assured her husband, although smelling of paint.[ref]SP 8/7/112, f.228: 24 July 1690[/ref] Soon after he left, she’d told him that visiting the ‘place made me think how happy I was there when I had your dear company’.[ref]SP 8/7/79, f.158: 5 July 1690[/ref]

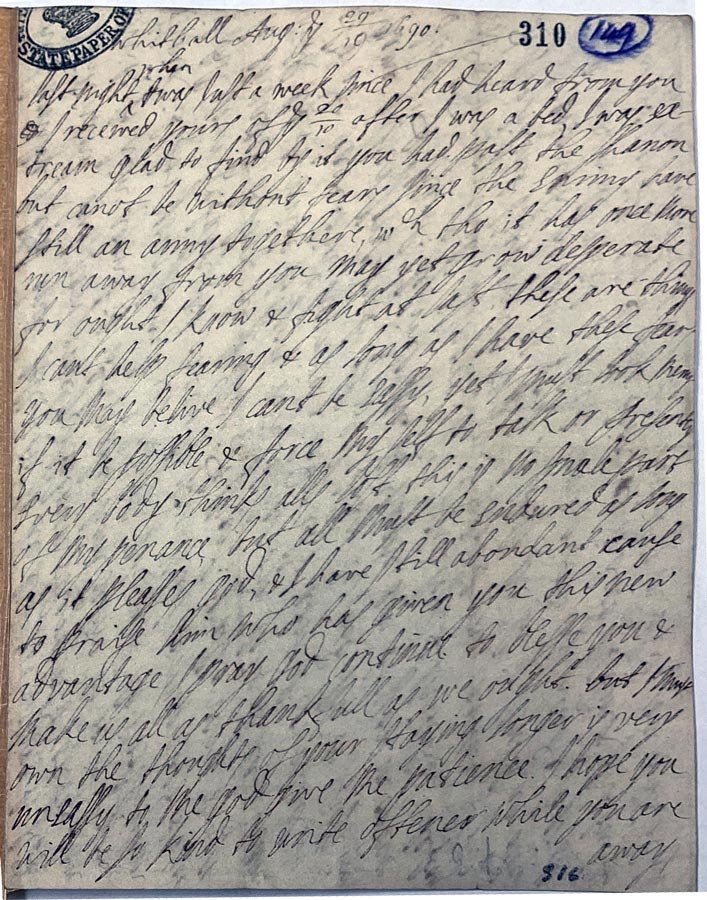

In one of her final letters of William’s absence, Mary wrote this:

‘I need not repeat hither how much I love you, nor how impatient I am to see you. You are kind enough to be persuaded of both, and I shall make it my ende[a]vo[u]r while I live never to give you cause to change your opinion of me, no more than I shall my kindness for you, which is much above imagination’.

SP 8/7/149, f.310

Reuniting and later years

Campaign ended, William returned to London – and to the woman he loved – in early September 1690. Their relationship was no fairy tale. There were rumours of infidelity on both sides – verified in William’s case. Gossips also hinted at same-sex attractions in respect of both William and Mary arising from their childlessness. On the other hand, evidence of at least one miscarriage, early in their marriage, is confirmed by a letter[ref]SP 8/3/32, f.61[/ref] from James to William from April 1678.

At the end of 1694, four years after the King’s Irish campaign, Mary died unexpectedly of smallpox. She was only thirty-two years old. The grief and tears of her famously buttoned-up husband was widely reported. William never re-married, and kept a lock of her hair next to his heart ever after. He was buried next to Mary in Westminster Abbey seven years later.[ref]Bowen, Marjorie The third Mary Stuart: Mary of York, Orange & England, being a character study with memoirs and letters of Queen Mary II of England, 1662-1694 (John Lane, 1929). Transcriptions of most of the letters in this blog appear in this work. pp 276-7, 288. [/ref]

From the evidence of King William’s Chest, it seems impossible to ignore the deep love shared between King William III and Queen Mary II. Sitting among the dry bones of official records, which comprise the lifeblood of the National Archives’ collection, the heartfelt sentiments and sweet-nothings contained in Mary’s love letters to her husband are quite a precious thing.

Really fascinating to read the Love Letters amongst all the other ” dry” letters and documents of state.. very enjoyable.Many thanks.

Thank you for this. I find it very interesting and appreciate the work that has gone in to preparing it.

very uplifting even in thee modern day. thank you. kathleen