2012 really seems to be the year of big royal anniversaries. Hot on the heels of The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, July marks the centenary of Crown copyright. It was in 1912 that that the Copyright Act of 1911 came into force and the concept of Crown copyright first made an appearance on the statute books.

Catalogue reference: WORK 25/69/B1/PR/3

The phrase ‘Crown copyright’ probably conjures up shelves of Royal Decrees and ancient parchments gathering dust in government archives. Although that is partly the case – except that the archives at Kew are in pristine condition and are anything but dusty or fusty – Crown copyright covers a wealth of government documents, both published and unpublished, produced by ministers and civil servants. So the term encompasses a huge wealth of documents including the Highway Code, Ordnance Survey maps, weather charts produced by the Met Office, government reports, government statistics and most information published on government websites. It also covers minutes written by government ministers and civil servants. This article, indeed, is covered by Crown copyright.

Ministers and civil servants are not generally renowned for their sparkling prose but it is interesting to note that in the past some of our most illustrious writers have written Crown copyright works. For example, Laurie Lee, of Cider with Rosie fame, once worked for the old Ministry of Information, as did H.E Bates, who went on to write the Darling Buds of May. And back in the 1960s, the poet Philip Larkin was commissioned by the Department of the Environment to write a poem about the environment. This resulted in Larkin’s poem Going, Going, Going.

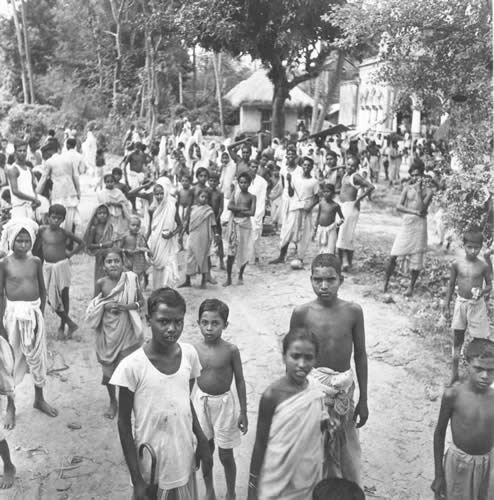

Crown copyright is not just about words on the page, however. Many images, photographs, posters and pictures are or were Crown copyright. In fact there is an extensive collection of images held by The National Archives’ Image library. Many of the artists and photographers who produced Crown copyright images were at the very top of their profession – one of the most notable was Cecil Beaton.

Bengali village scene, India, photographed by Cecil Beaton, 1940s. Catalogue reference: INF 14/435

Some people might say that Crown copyright is a bit of an anachronism and harks back to an earlier era. How does Crown copyright actually fit into the world of the internet and the concepts of open data? Surely, some might argue, Crown copyright acts as a block to people being able to access and re-use public information? Well actually it doesn’t. If each government department held copyright in its own right it could lead to inconsistency and all sorts of bureaucratic hurdles for people who want to use and re-use government information. However, the fact that most government information is managed centrally on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office means that a streamlined and consistent approach to licensing can be adopted.

Whoa there, I hear you ask, who is this Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office? Is this some government official who is responsible for counting paper clips and pens? The Controller is a historical title going back about 200 years. The Controller used to head the former government department Her Majesty’s Stationery Office – or HMSO for short – which used to provide printing, stationery and publishing services for government. Most of the trading functions of HMSO were privatised in 1996 but certain activities, including the management of Crown copyright, were retained within government.

The Controller’s responsibilities for Crown copyright derive from personal appointment from Her Majesty the Queen, literally to manage all Crown-owned copyrights as though they were the Controller’s personal property. The current Controller is Carol Tullo, Director of Information Policy and Services at The National Archives. Carol is a barrister by profession and I have it on good authority that she has little interest in counting paper clips or pens.

For many, copyright is a mechanism for the commercial exploitation of literary and artistic works. Sometimes this means that the terms of use as set out in licensing conditions can be onerous and restrictive. This is not the case with Crown copyright however. The National Archives has for a number years championed the use of simple, enabling licences that encourage people and companies who want to use and re-use Crown copyright material. This approach led to the development of the Open Government Licence (OGL) which was launched in 2010. The OGL is unlike practically any licence that you can think of. Far from being crammed full of legalistic jargon and a string of things that you can’t do, the OGL, by contrast, is a licence which is expressed in plain English and actively enables people to use Crown copyright in all sorts of innovative ways. All we ask for is that government information is not used in a way that sets out to deliberately mislead the public. We also ask that Crown copyright is properly acknowledged so that others may be able to identify and use it.

So far from being something that restricts, we in The National Archives like to think that Crown copyright provides a mechanism which allows publishers, information providers and the public to use and re-use a wide range of government information in many different ways. This is really open government in action.

Spoken like a true bureaucrat. Open Government and Crown Copyright is an oxymoron.

I thought that the article is good, there are odd pieces in government files to show civil servaants have a sense of humour, like the life of the Treasury Adviser to the United Nations and ‘Treasury slang’. As some scifi people may recall HMSO made it into Dr Who!.

Mark – only if you interpret “copyright” as restrictive and not an enabler to clarify how open terms of re-use can be? It is a bit like saying “open licensing” is an oxymoron. Even in 2012, quality issues and knowing the status of the authorship as Crown is important to users. It may change but the Crown means it is from government.