Military map surveyors and the early history of the Ordnance Survey have long been subjects of historical study. Recently, The National Archives undertook a two-week cataloguing project to add to our knowledge of some of the Draughtsmen involved in the later 18th century.

Details of the careers of more than 200 of these men now enhance the online catalogue Discovery, using information from a card index compiled during the 1960s. The index related to War Office record series, which include appointment and establishment books, reports, correspondence, and registers of plans. Discovery now lists men’s names together with dates and brief details, such as posts to which they were appointed[ref]The card index includes 325 references of individual appointments relating to 227 men. The data refers to 13 piece numbers within five War Office series: WO 34/206 among papers of Baron Amherst, Commander in Chief 1712-1786; WO 44/517-WO 44/518 Correspondence between the Ordnance Office and the War Office, these volumes dated 1816-1823; WO 46/10 in Ordnance Office out-letters, this volume dated 1775-1777; WO 54/199, 207-208, 214-215, 217, 517; WO 55/419 Register of Artillery Pensions, Ireland, dated 1831 and WO 55/2281 Index of Correspondence about Ordnance Plans and Drawings 1700-1819.[/ref].

The men whose careers are detailed in these volumes were the early cartographers of what we now know as the Ordnance Survey. They set the framework and standards for national mapping, which would be used throughout Britain and the British Empire.

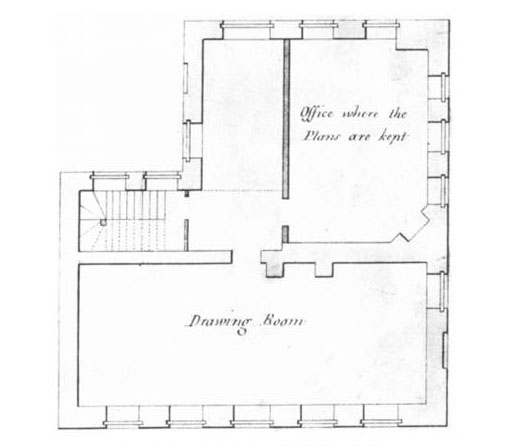

Most men started their careers in the Drawing Room at the Tower of London, formally established in 1752, in the Board of Ordnance, which provided supplies for the army, including maps. In the early period especially, Draughtsmen were often appointed through social connection[ref]Douglas W Marshall, ‘Military Maps of the Eighteenth-Century and the Tower of London Drawing Room’, Imago Mundi, 32, (Lympne, 1980), pp. 22-23.[/ref]. This is mirrored in the index cards with professions of the fathers of 20 men also listed alongside their own appointments.

From summer 1752 a classification system was introduced in the Drawing Room, with a Chief Draughtsman to oversee five classes of Draughtsmen[ref]Marshall, ibid.[/ref]. A number of these appointments are now listed in the piece descriptions. While some men made a career in the Drawing Room and stayed there for many years, over half gained promotions in other departments of the Ordnance and the Army, often within the Royal Engineers.

In 1800 the civilian staff of the Drawing Room officially became the Royal Corps of Military Surveyors and Draughtsmen, and were absorbed into the Army. The Corps was disbanded in 1817 but many of the men were retained to work on the Trigonometrical Survey, which established precise geographic locations of hundreds of landmarks in the UK to be used in topographic surveys. Many of the plans and maps they produced throughout their careers are now housed in the collections at The National Archives.

A notable cartographer who appeared in the project data was Robert Dawson, father of Robert Kearsley Dawson, who oversaw the Tithe Survey of England and Wales and compiled the detailed instructions for the production of the tithe maps. Dawson the elder was renowned for his depictions of relief and topography, which he evidently passed onto his son.

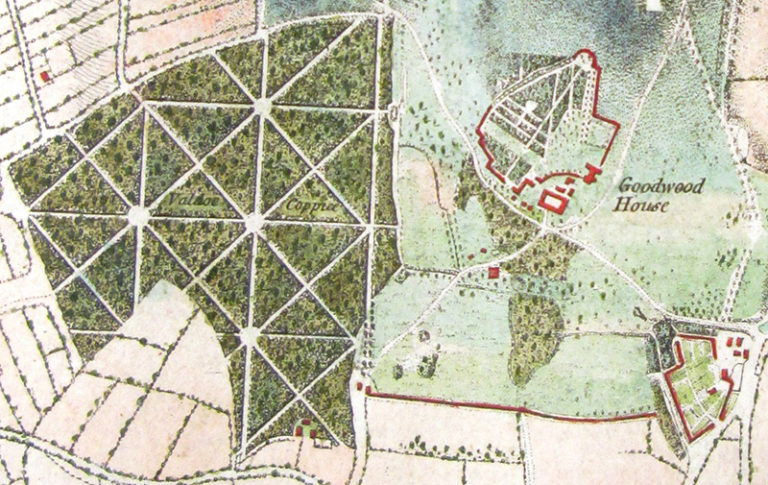

Dawson largely owed his place in cartographic history to another man who features in the index, William Gardner, who in the 1780s saw Dawson’s talents and arranged for his employment by the Board of Ordnance[ref]R Hewitt, Map of a Nation, (Granta, 2011), p. 179.[/ref]. Gardner is perhaps better known for his work with Thomas Yeakell, also listed in the card index, and their work for the 3rd Duke of Richmond on his large estate at Goodwood, Sussex. Here Gardner and Yeakell honed their map-making skills, as evident in their survey of the County of Sussex in 1778-1780.

The Duke of Richmond ensured that Yeakell and Gardner were employed among the Draughtsmen in the Tower of London. Gardner went on to oversee production of the first Ordnance Survey maps, almost certainly influenced by his work with Yeakell on the map of Sussex[ref]R Mitchell and A Janes, Maps their Untold Stories, (Bloomsbury, 2014), p. 92.[/ref]. He attained the positions of Chief Draughtsman and later Chief Surveyor.

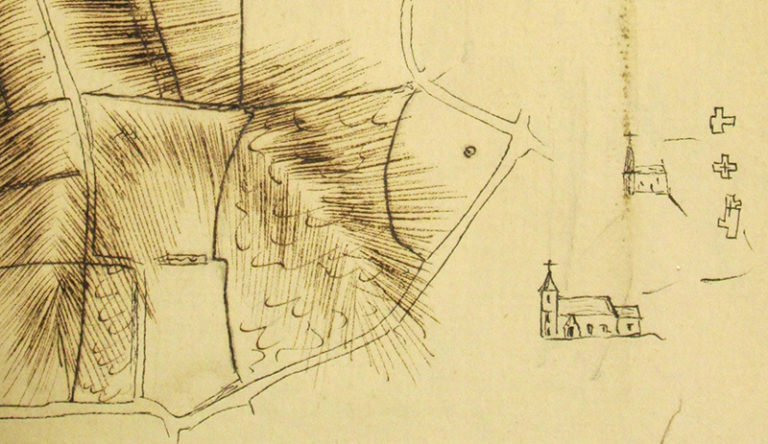

As well as finished maps, there survive ‘foul plans’ made by some of these men. These are rare survivals of the working plans or sketches from which the final map developed. The extract below by Thomas Yeakell shows topography and roads with a drawing in the margin of a church in both plan and elevation. The sketch is also littered with words and calculations giving a glimpse into the map-making process outside the Drawing Room.

Foul plans or rough sketches made by some of the other cartographers have also survived, including Charles Budgen’s plan of Hampshire, commonly referred to as ‘Budgen’s Rough Plans’ (MPHH 1/220 and MPH 1/580)[ref]I Parr, ‘Topographical survey and early Ordnance Survey maps at The National Archives: Public Record Office’, Sheetlines (2003), pp.35-43.[/ref].

A lesser-known man who appeared in the project data was Reuben Burrow, who is noted as ‘Mathematical Master [in the Drawing Room], 1776’. He was assistant to Neville Maskelyne and accompanied him on his trip to Schiehallion in Scotland in 1774 for an experiment to establish the density of the Earth. While Maskelyne undertook his observations and calculations, Burrow made a detailed survey of the mountain. The data from the trip was passed to Charles Hutton, professor of mathematics at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, to calculate the volume of the mountain. During this work Hutton used contour lines on his maps, instead of the traditional hachuring then used by British map-makers, which became one of the distinctive features of the Ordnance Survey maps we know so well today[ref]R Hewitt, ibid, p.63.[/ref]. Burrow later travelled to India for research[ref]Leslie Stephen (ed), ‘Reuben Burrow’, in Dictionary of National Biography Volume 7, (Macmillan, 1885-1900), pp.448-449.[/ref].

Occasionally the card index listed postings abroad. One of these appointments was that of Francis Assiotti to Minorca, from which he produced the map below. Although it has many aesthetic qualities, including the maritime-themed cartouche, it gives a distinctive nod to military endeavours. The insets detail the entrance to the Mediterranean and the settlement of Georgetown, now named Es Castell after the adjacent fort of St Phillip’s Castle. Assiotti is also known for his ‘List of Maps and Plans Belonging to the … Commissioners for Trade and Plantations’ of 1780 (CO 326/15). This inventory is often used by historians to trace the movement of maps.

This project has helped draw detail on the careers of some of the early cartographers of the Ordnance Survey, based on a partial card index. Many more names are contained within these volumes, reports and registers, but it is hoped this project may pave the way for further enquiry and research.

Although the map may not be the territory – as the saying (almost) goes – the illustrations that accompany this post show that it can be a beautiful piece of artwork.

Thank you for this blog on military maps in the Drawing Room. I am writing a book on an 18th-century military engineer/draughtsman named William Booth, who entered the Drawing Room in 1760. I wonder if you might have picked him up in your cataloguing exercise?

Also, do you know whether draughtsmen who went through the Drawing Room and eventually attained commissions in the Corps of Engineers would have had to attend the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich for more education?